Jul 10, 2018

'Chart of the century' shows Fed what could become of Trump's trade war

, Bloomberg News

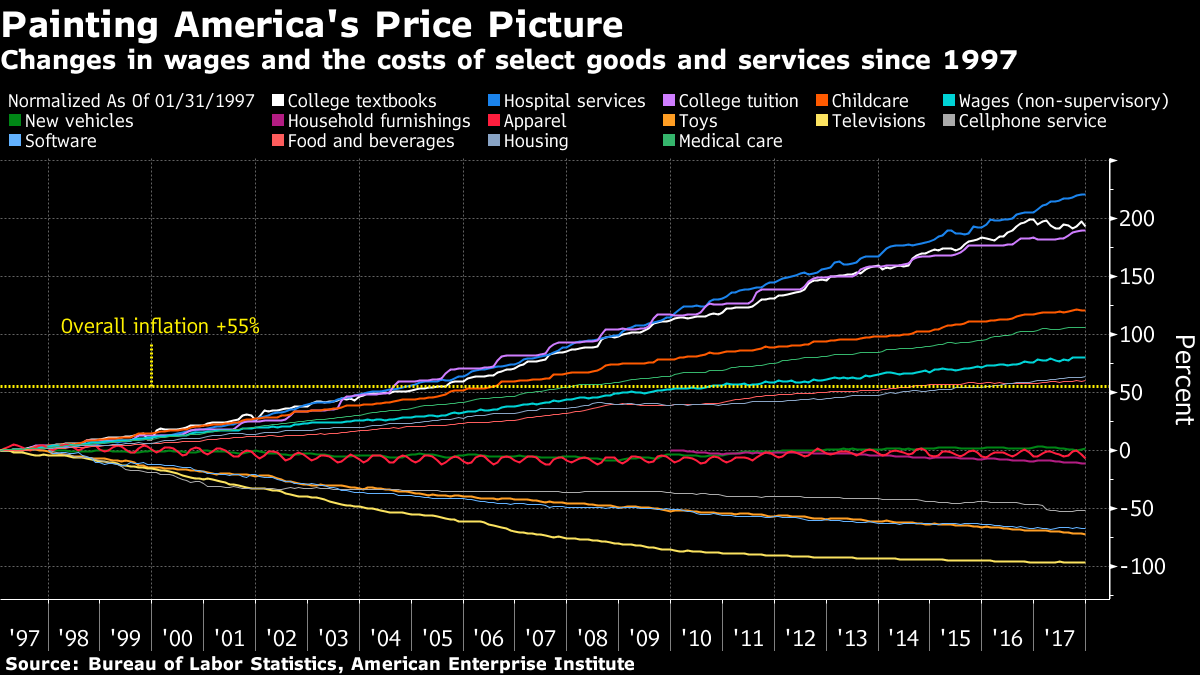

A multi-colored graphic that’s made the rounds at the Federal Reserve hints at what Chairman Jerome Powell could face if President Donald Trump succeeds in throwing globalization into reverse: Higher prices for many goods and potentially faster inflation.

Plugged as possibly the chart of the century by economist and originator Mark Perry, it shows that prices of goods subject to foreign competition -- think toys and television sets -- have tumbled over the past two decades as trade barriers have come down around the world. Prices of so-called non-tradeables -- hospital stays and college tuition, to name two -- have surged.

“We would have fewer choices, potentially less quality, less productivity and higher prices if we reverse globalization,” said Timothy Adams, president of the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, who’s discussed the chart and its implications with Fed policy makers.

Just as globalization has been a headwind holding back inflation, its unraveling could end up being a tailwind in the years ahead, pushing costs higher as countries and companies retreat from the international marketplace. That would be on top of the one-time effect that Trump’s tariffs will have on prices of selected imports, putting pressure on the Fed to raise interest rates at a faster pace than the gradual path it has currently mapped out.

The president has already imposed import duties on a wide range of products, from steel and aluminum to washing machines and farm equipment. He’s taken particular aim at shipments from China, levying US$34 billion in tariffs on goods from that country last week. China, Canada and some of the other nations affected have responded in kind.

Administration officials argue that Trump’s tariffs are designed to convince other countries to dismantle trade barriers, not erect new ones. Yet experts are skeptical, pointing to the president’s focus on getting rid of America’s bilateral deficits and his repeated attacks on the North American Free Trade Agreement, which eliminated many tariffs among the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

“We’re not getting concessions from other countries,” said Dartmouth College professor Douglas Irwin, author of the recently published “Clashing over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy.” “We’re getting other countries angry at us and they’re retaliating.”

For years, globalization has “imparted a steady dis-inflationary bias” on open economies such the U.K. and U.S. because of competition from lower-cost foreign producers and lower paid foreign workers, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney said last September.

Now there are small hints of what could happen if that goes into reverse.

National Association of Home Builders Chairman Randy Noel said last month that record-high lumber prices have added nearly US$9,000 to the price of a new single-family home since January 2017. The U.S. in November imposed average import duties of 21 per cent on Canadian shipments of timber.

Prices of washing machines sold in the U.S. have also surged after the administration acted to restrict imports earlier this year.

Fed policy makers have signaled that they’ll consider such direct price impacts as temporary and not necessarily indicative of a shift in underlying inflation trends.

But distinguishing between the two might not be that easy, given that inflation is already on the rise and the economy is being juiced by fiscal stimulus late in an expansion, said Ellen Zentner, chief U.S. economist for Morgan Stanley in New York.

In a sign of the difficulties the central bank might face, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard told reporters last month that some suppliers were using the threat of new tariffs as a reason to raise prices, even when new tariffs would not directly target their business.

“The risk is the Fed could make a policy mistake” by increasing interest rates more aggressively in response, Zentner said, though she doubts that will happen.

Consumers, for their part, appear convinced that the Fed will be able to hold the line on inflation. The monthly reading on consumer prices for June will be released at 8:30 a.m. on Thursday in Washington.

While households see inflation ticking up over the next year due to tariffs and higher energy prices, they seem to believe that the rise will be temporary, Richard Curtin, director of the University of Michigan consumer surveys, said.

That’s allowing policy makers to focus more of their attention on the potential impact of the tariff battles on growth than on inflation.

At their meeting last month, most Fed officials voiced concern that trade uncertainty “eventually could have negative effects on business sentiment and investment spending,” according to the meeting’s minutes released last week.

The economic fallout would spread if multinational companies scale back their decades-long drive to build up global supply chains and instead concentrate on making more at home.

“There would be long term effects on the efficiency of production in the global economy,” said chart author Perry, who is an economics professor at the University of Michigan.

And potentially on inflation.

The increased use of global supply chains in recent years has tended to hold down prices, according to research by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Kristin Forbes.

“So if this went into reverse, this could boost inflationary pressures,” the former Bank of England policy maker said in an email.