Jan 21, 2022

Debt-strapped Canadians brace for a risky rate-hiking cycle

, Bloomberg News

Debt-strapped Canadians brace for a risky rate-hiking cycle

The era of historically low interest rates, which inflated Canadians’ wealth and facilitated their spending, is coming to an end.

As early as next week, the Bank of Canada will start a campaign of tighter monetary policy that will test the country’s debt-laden consumers and reveal whether its robust economic recovery has staying power.

The country has one of the highest total debt burdens in the developed world, ranking slightly behind France and well ahead of the U.S. Even so, markets are betting that the Bank of Canada will be the most aggressive Group of Seven central bank in lifting rates.

Economists and traders see a string of hikes, likely starting at the Jan. 26 decision, until the policy rate is back at the pre-pandemic level of 1.75 per cent in about a year. The Bank of Nova Scotia is forecasting it will climb as high as 2 per cent.

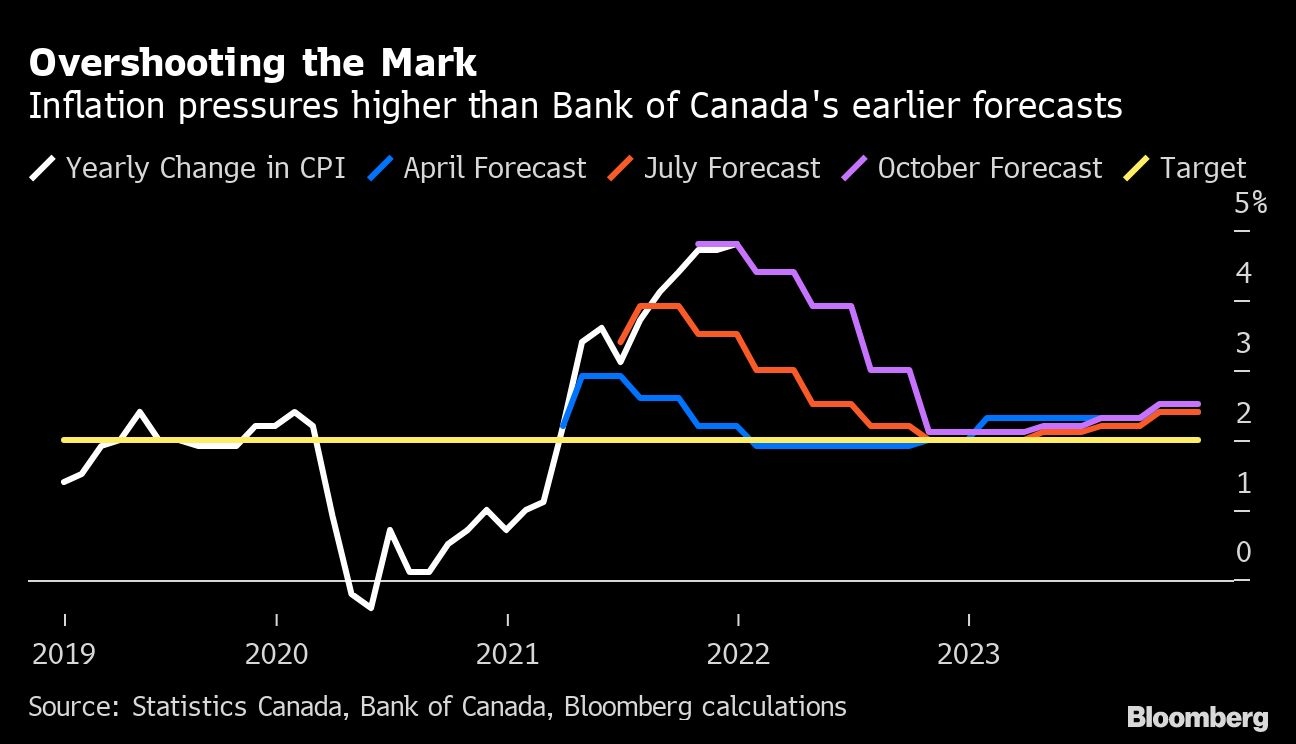

The best case is that higher rates don’t produce a sharp economic slowdown but are still potent enough to cool inflation significantly. Consumer prices rose at the fastest pace in 30 years last month.

But the potential for policy error has escalated along with inflation.

Central bank officials led by Governor Tiff Macklem will worry that if they move too quickly, they will destabilize an economy that has one of the most expensive real-estate markets in the world. But they also know that if they balk, they could lose control of consumer prices and squander credibility that’s taken three decades to build.

It’s nearly as tricky for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

It’s getting difficult for him to justify budget deficits. But pressure to help Canadians with the rising cost of living could escalate demands for continued government help. Fiscal expansionism has been at the center of the prime minister’s agenda for six years and was a big part of his re-election campaign in 2021.

“We are entering possibly the riskiest economic policy landscape we’ve seen in decades,” Robert Asselin, a former Trudeau adviser who is now vice-president at the Business Council of Canada, said by phone.

In one way, the normalization of rates from record lows is a success story. It reflects an economy that’s recouped its pandemic losses, is approaching full employment and running up against capacity.

The nation created 886,000 new jobs in 2021, a record year. After losing 3 million jobs at the start of the pandemic, employment is now 240,500 above where it was in February 2020. In the U.S., employment is still almost 3 million below that mark.

Commodities have also been doing well, helping to fuel national income. Yet, analysts also worry about the soundness of the recovery, which has relied on a surge in housing and one of the largest fiscal expansions (and increases in central bank balance sheets) anywhere.

Home prices have risen 41 per cent since policy makers slashed interest rates to the emergency lows in March 2020. Total private and public debt outside of the financial sector, meanwhile, has risen by more than $1 trillion (US$802 billion) to $8.1 trillion through June last year.

That represents about 345 per cent of gross domestic product, the sixth highest among the more than 40 rich economies tracked by the Bank for International Settlements. How the economy will react to higher borrowing costs remains unknown.

“I don’t think you want to turn the screws on housing too much, too quickly,” Benjamin Reitzes, macro strategist at Bank of Montreal, said by phone. “There’s some risk there and you want to make sure that market stays stable.”

Others believe the central bank is already behind the curve with limited options. Amid signs price pressures have broadened, a gradual approach may fail to slow inflation -- forcing even more aggressive tightening down the line.

“We can’t guarantee a soft landing, but decisions made by the Bank of Canada very soon will go a long way toward determining whether we stand a chance,” Derek Holt, an economist at Scotiabank, said Thursday in a report to investors. “Canada is indeed at a fork in the road.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“We expect the BoC will not touch its rate lever at the January meeting, but risks tilt to an earlier move than our current April baseline.”

--Andrew Husby, economist

Trudeau is facing a similar dilemma.

Throughout the pandemic, he and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland have sought to keep the economy flush with cash, while proposing an expansive social policy and climate-change agenda.

At a news conference Wednesday, Trudeau gave little indication he plans to pare back spending. According to the parliamentary budget watchdog, the government is facing a $160 billion shortfall in the fiscal year that ends March 31 and there are nearly $50 billion worth of election promises that have yet to budgeted.

“We’re going to continue to work to bring down costs for families on housing, childcare, in a range of things,” the prime minister told reporters, saying his government would “have Canadians’ backs as we promised in the very beginning of the pandemic.”

The risk is that without trimming his fiscal plans, Trudeau will fuel inflation that could drive the Bank of Canada to raise borrowing costs by even more. That would leave the nation’s indebted households to pay the biggest price for the prime minister’s ambitions.

To some, that’s a risky bet.

“The challenge that lies ahead is to not let policy errors harm the impressive recovery we have seen over the last few months,” Asselin said.