Jul 1, 2020

Did a Chinese hack kill Canada's greatest tech company?

Did a Chinese hack kill Nortel?

The documents began arriving in China at 8:48 a.m. on a Saturday in April 2004. There were close to 800 of them: PowerPoint presentations from customer meetings, an analysis of a recent sales loss, design details for an American communications network. Others were technical, including source code that represented some of the most sensitive information owned by Nortel Networks Corp., then one of the world’s largest companies.

At its height in 2000, the telecom equipment manufacturer employed 90,000 people and had a market value of $367 billion (about US$250 billion at the time), accounting for more than 35 per cent of Canada’s benchmark stock market index, the TSE 300. Nortel’s sprawling Ottawa research campus sat at the centre of a promising tech ecosystem, surrounded by dozens of startups packed with its former employees. The company dominated the market for fiber-optic data transmission systems; it had invented a touchscreen wireless device almost a decade before the iPhone and controlled thousands of fiber-optic and wireless patents. Instead of losing its most promising engineers to Silicon Valley, Nortel was attracting brilliant coders from all over the world. The company seemed sure to help lay the groundwork for the next generations of wireless networks, which would be known as 4G and 5G.

Back then, Ottawa, not traditionally (or since) known for its glamour, seemed full of sports cars, corporate jets, and even society scandals featuring tech CEOs. In 1999 the co-founder of Corel Corp., who’d gotten his start at Nortel’s precursor company, threw a gala at which his wife showed up in a $1-million leather bodysuit with an anatomically-correct gold breastplate and a 15-carat-diamond nipple. “You were just surrounded by the most interesting and intelligent people that you could find anywhere in the world,” says Ken Bradley, who spent 30 years at Nortel, including as a chief procurement officer. “Nobody would ever tell me I couldn’t do something.”

Nortel’s giddy, gilded growth also made it a target. Starting in the late 1990s, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the country’s version of the CIA, became aware of “unusual traffic,” suggesting that hackers in China were stealing data and documents from Ottawa. “We went to Nortel in Ottawa, and we told the executives, ‘They’re sucking your intellectual property out,’ ” says Michel Juneau-Katsuya, who headed the agency’s Asia-Pacific unit at the time. “They didn’t do anything.”

By 2004 the hackers had breached Nortel’s uppermost ranks. The person who sent the roughly 800 documents to China appeared to be none other than Frank Dunn, Nortel’s embattled chief executive officer. Four days before Dunn was fired — fallout from an accounting scandal on his watch that forced the company to restate its financial results — someone using his login had relayed the PowerPoints and other sensitive files to an IP address registered to Shanghai Faxian Corp. It appeared to be a front company with no known business dealings with Nortel.

The thief wasn’t Dunn, of course. Hackers had stolen his password and those of six others from Nortel’s prized optical unit, in which the company had invested billions of dollars. Using a script called Il.browse, the intruders swept up entire categories from Nortel’s systems: Product Development, Research and Development, Design Documents & Minutes, and more. “They were taking the whole contents of a folder — it was like a vacuum cleaner approach,” says Brian Shields, who was then a senior adviser on systems security and part of the five-person team that investigated the breach.

Years later, Shields would look at the hack, and Nortel’s failure to adequately respond to it, as the beginning of the end of the company. Perhaps because of the hubris that came from being a market leader, or because it was distracted by a series of business failures, Nortel never tried to determine how the credentials were stolen. It simply changed the passwords; predictably, the hacks continued. By 2009 the company was bankrupt.

No one knows who managed to hack Nortel or where that data went in China. But Shields, and many others who’ve looked into the case, have a strong suspicion it was the Chinese government, which weakened a key Western rival as it promoted its own technology champions, including Huawei Technologies Co., the big telecom equipment manufacturer. Huawei says it wasn’t aware of the Nortel hack at the time, nor involved in it. It also says it never received any information from Nortel. “Any allegations of Huawei’s awareness of or involvement in espionage are entirely false,” the company says in a statement. “None of Huawei’s products or technologies have been developed through improper or nefarious means.”

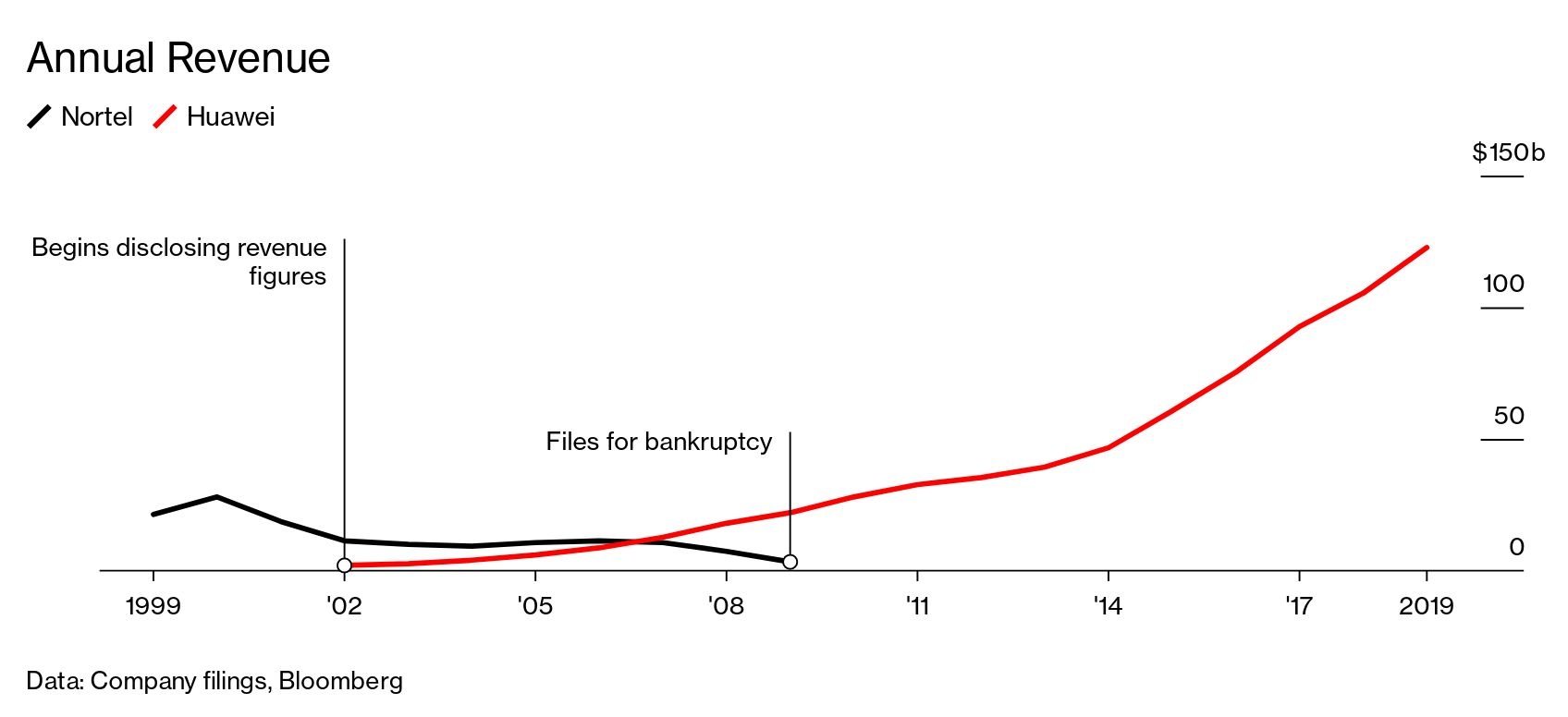

What isn’t in dispute is that the Nortel hack coincided with a separate offensive by Huawei. This one was totally legal and arguably even more damaging. While Nortel struggled, Huawei thrived thanks to its unique structure — it was privately held, enjoyed generous credit lines from state-owned banks, and had an ability to absorb losses for years before making money on its products. It poached Nortel’s biggest customers and, eventually, hired away the researchers who would give it the lead in 5G networks. “This is plain and simple: Economic espionage did in Nortel,” Shields says. “And all you have to do is look at what entity in the world took over No. 1 and how quickly they did it.”

Most people know Huawei for its cellphones. The company started selling cheap knockoff phones around 2004 and went on to produce models with top-of-the-line processors, big screens, and slick software. Today it’s No. 2 — behind Samsung Electronics Co. and ahead of Apple Inc. — in the phonemaking business.

But Huawei’s real power lies in its control over the plumbing of the Digital Age. The company sells routers and switches that direct data, servers that store it, components for the fiber-optic cables that transmit it, radio antennas that send it to wireless devices, and the software to manage it all. It’s willing to build those networks pretty much anywhere on the planet, including Mount Everest, the Sahara, and north of the Arctic Circle.

Ren Zhengfei, a former military engineer, founded Huawei in 1987 in Shenzhen, China’s testing ground for capitalism. The government wanted to reduce the telecom sector’s almost-total dependence on foreign equipment, and Huawei was one of hundreds of companies that aimed to speed the process. Ren targeted China’s neglected rural hinterlands, where Huawei became an expert at supplying gear that was cheap, reliable, and easy to maintain.

Huawei began plowing money into R&D as soon as it could. By the mid-1990s it was winning larger contracts, often by aggressively undercutting rivals. It overtook Shanghai Bell as the largest domestic maker of switches by bundling free equipment with its contracts. In routers, it took China’s No. 1 spot away from Cisco Systems Inc. by offering a 40-per-cent price break on comparable gear.

By the 2000s, Huawei was taking its strategy overseas, with the help of US$10.6 billion in credit from China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, both controlled by Beijing. Its credit line would reach US$100 billion over the next decade. Huawei, acting as a Chinese national champion, could offer telecom operators and mobile carriers low-cost long-term loans from the state banks to buy its equipment. (In 2012 the company told a U.S. congressional committee that customers borrowed only US$5.9 billion of the US$100 billion from 2005 to 2011.)

In 2005 the China Development Bank lent the Nigerian government US$200 million to buy Huawei equipment for a national wireless network, offering an absurdly low interest rate, as little as one per cent, according to a study by the Japan External Trade Organization. (The benchmark rate at the time was more than six per cent.) Huawei’s overseas sales had been US$50 million in 1999. By the end of 2005, they’d surged 100-fold, to US$5 billion.

Around this time, Western companies began complaining about intellectual-property theft — complaints Huawei denied or chalked up to misunderstandings. Even so, the established telecom companies mostly ignored Huawei, seeing it merely as a low-cost competitor that would have trouble competing in their home markets. But in 2005, the company stunned the industry, winning a piece of a £10 billion (US$19 billion) project to replace 16 national phone networks in the U.K. with a single digital one. Nortel and the telecom Marconi Corp. lost out. Then, in 2008, Huawei beat out Nortel on its home turf, landing a contract as part of a $1 billion wireless network in Canada for Telus Corp. and BCE Inc.

In both cases, the Western buyers cited the technical strength of Huawei’s proposals. But it’s widely believed that the gear Huawei sold was also much, much cheaper. The company had a reputation at the time for initially offering its products at an enormous loss to get a foothold and win upgrades and services down the line. This prompted concerns, especially in the U.S., that Huawei would eventually own much of the world’s critical telecom infrastructure because of its backing from China. “None of the G7 countries provide levels of financing anywhere near those of the China Development Bank,” said Fred Hochberg, then head of the Export-Import Bank of the U.S., in a 2011 speech. “That keeps me up at night.”

Huawei notes that its rivals enjoy backing from their own governments, though publicly available data suggest it’s much more modest than what Huawei has enjoyed. During the 1990s, Nortel financed its deals mostly with its own cash, which led to enormous losses when the dot-com bubble burst and telecom startups that had bought its equipment went out of business.

Despite that, and despite losing big contracts to Huawei, there were signs that Nortel was turning a corner by 2008. But then the global financial crisis froze credit markets, sending it again into crisis. Executives had hoped the Canadian government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper would bail out Nortel, but Harper instead focused on the auto industry, paying $13.7 billion for equity stakes in General Motors Inc. and Chrysler LLC, hoping it would help persuade the American companies to keep their Canadian factories open.

The investment was a bust: Canada lost $3.7 billion on the deal, according to calculations by the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, and GM shuttered an enormous plant in Oshawa, Ont., anyway. Meanwhile, Nortel’s most promising business units were bought up by rivals including Ericsson, Ciena, and Avaya. “Stephen Harper dropped the ball on Nortel,” then-Liberal Party leader Michael Ignatieff said in September 2009. “He let a Canadian champion fail.”

In 2013 the cybersecurity company Mandiant announced it had completed an exhaustive investigation into alleged cyberattacks on 141 companies in the U.S., Canada, and other mostly English-speaking nations over the previous nine years. Researchers found that in almost every case, the data led back to a district in Shanghai near a Chinese military unit tasked with spying on computer networks in the U.S. and Canada. Mandiant, which is now a division of FireEye Inc., was saying aloud what many already suspected: The Chinese government was directly involved in economic espionage.

Huawei itself has been repeatedly accused of intellectual-property theft, most famously in 2003, when Cisco said the Chinese company had stolen source code verbatim from a router, cloning its help screens and even copying its manuals, typos and all. In another suit alleging IP theft, Quintel Technology Ltd., a developer of wireless antennas in Rochester, N.Y., cited a Huawei patent application in the U.S. that contained a copyright notice crediting “Quintel Technology Limited 2009.”

Huawei denied the allegations in both cases, and both companies eventually settled. But earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Huawei with racketeering and conspiracy to steal trade secrets, accusing it of theft from six companies. Huawei has called the charges “unfounded and unfair,” saying they rest on “recycled civil disputes from the last 20 years that have been previously settled, litigated, and, in some cases, rejected by federal judges and juries.” It’s being targeted “for reasons related to competition rather than law enforcement,” it said in a statement in February.

China has repeatedly denied conducting cyber espionage on behalf of companies, but many Western intelligence officials and tech executives don’t buy this. In June former Google Chairman Eric Schmidt revived allegations about Huawei building backdoors into its technology. “There’s no question that information from Huawei routers has ultimately ended up in hands that would appear to be the state,” he told the BBC, likening the company to a spy agency. And earlier this year at a conference, U.S. Federal Communications Commissioner Brendan Carr called out “China, and Huawei that does their bidding,” adding, “they have a list of malign conduct longer than a CVS receipt.” Hanging over all of this is the 2018 arrest of Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou (Ren’s eldest daughter) in Canada on U.S. fraud charges. China immediately jailed two Canadians, a move widely seen as retaliatory. Meng, who is currently out on bail in Canada while she fights extradition, maintains her innocence.

Huawei, which strenuously denies any relationship with the Chinese government, has at times resorted to a kind of corporate theater to prove its point. Over the past few years, the company has invited foreign reporters to its Shenzhen headquarters to inspect its shareholder list, a 10-volume set it keeps behind glass. (The books contain names of employees, who Huawei says are its only stockholders. None of the listed shareholders is a government agency or official.) That’s failed to convince critics, who point out that Chinese law obligates companies to cooperate with national intelligence work and to keep those requests secret. In other words, if asked, Huawei would have to spy for the state and cover up that spying. (U.S. companies have been accused of similar behavior, most famously following leaks by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden.)

Whoever did it, the Nortel attack was in some respects even worse than other well-known cases of alleged cyber espionage. It lasted from at least 2000 to 2009, twice as long as any of the hacks in the Mandiant study. Shields says the techniques were sophisticated — obviously the work of state actors rather than a private company. Nortel executives, consumed by the company’s turnaround attempt, did almost nothing. Two board members say it never came up even though they were meeting management almost weekly in 2004. Dunn, the fired CEO, wasn’t informed, because he was ousted before the breach was detected and replaced by Bill Owens, a company director and retired U.S. Navy admiral.

But over the next five years — as its security team would discover the hack, probe it, then set it aside — Nortel, a global technological juggernaut, would respond to one of the longest-running Chinese hacks of the decade with a password update and a series of overtures to Huawei. Owens met repeatedly with Ren about a possible merger. He stepped aside in November 2005 for Mike Zafirovski, who in his previous job as chief operating officer at Motorola Inc. had nearly closed a secret deal to buy Huawei two years earlier. Under Zafirovski, Nortel and Huawei discussed a joint venture in routers and switches, a sale of its Ethernet division, and even a potential rescue during its final weeks.

None of those panned out, which may not have mattered much to the Chinese company, because as Nortel was collapsing, Huawei quietly hired about 20 Nortel scientists who’d been developing the groundwork for 5G wireless technology.

Today, Huawei’s research center in Ottawa doesn’t quite have the excitement of Nortel’s old campus. The company’s “Stealth Building” still evokes vitality, but it’s of a different sort. The five-story structure was designed to resemble the radar-evading silhouette of a B-2 bomber.

The lab houses the research of Wen Tong, once Nortel’s most prolific inventor and now the chief technology officer for Huawei’s wireless business. Tong led the exodus from Nortel to Huawei in 2009, after spending 14 years at the Canadian company. An electrical engineer by training, he’d emigrated from China to study at Montreal’s Concordia University and had amassed more than 100 patents in wireless research, generating some of Nortel’s most valuable intellectual property. When Nortel’s patent portfolio was finally sold off in bankruptcy in 2011 for a record US$4.5 billion to a consortium including Apple and Microsoft Corp., the most prized of the batch were ones related to technologies his team had developed.

Up until Nortel’s collapse, Huawei had been a follower, not an innovator — “a second-fast mover” that could do things better and cheaper, says Song Zhang, Huawei’s vice president for research strategy and partnerships, who’d also worked at Nortel in the late 1990s. It was keen to join the small ring of mostly Western companies dominating next-generation wireless research.

Thousands were looking for jobs in Ottawa, and Huawei offered scientists such as Tong an increasingly rare kind of sanctuary: a well-funded lab focused on basic science, not product development, modeled after Bell Labs and Xerox Corp.’s Parc, the great drivers of 20th century American innovation. “They wanted to continue doing research, and they felt Huawei would invest in that,” Zhang says.

Tong was particularly interested in a problem that would prove crucial to the future of wireless communications. For years at Nortel he’d been studying data interference, which was becoming increasingly worse as data transfer speeds improved. The problem is a bit like the way an open window drowns out the radio as a car accelerates. In the mid-20th century, mathematician Claude Shannon calculated a maximum theoretical speed for transmitting information error-free, but for decades, researchers around the world had puzzled over how to reach it.

Tong brooded over the problem, earning him the nickname “Nortel’s answer to Claude Shannon.” He thought he spotted the answer in an arcane scientific paper on something called polar coding, a way of using algorithms to correct for errors. Pursuing it was risky, but with Huawei’s backing, he took the gamble and spent years trying to turn the idea into a crucial part of 5G technology.

Those efforts would pay off at a 2016 industry conference to set standards for the next generation of wireless infrastructure. Western companies had dominated these conferences in the past, but this time, all the Chinese companies lined up behind Huawei in favor of Tong’s protocol against a camp that favored sticking with an existing approach Qualcomm Inc. had developed. (Lenovo Group Ltd., the Chinese computer maker, had initially sided with the Western-led bloc before switching to Huawei’s side. The company’s founder later issued a public rebuttal after being accused of being traitorous on Chinese social media.)

“Nobody could agree to anything,” says Mike Thelander, the founder of Signals Research Group, who attended the gathering. It seemed clear the Chinese government had pressured its companies not to break ranks with Huawei, he says. The company was also proud of its solution and convinced of its merits. “Huawei had spent so much effort in R&D on polar coding, they just would not give in,” Thelander says. Eventually, around 2 a.m., a compromise was reached: Polar coding was adopted alongside the other protocol. Huawei, in other words, would be central to the development of 5G.

Being the standard setter ensures Huawei royalty payments for years to come. But more important, those who define the standards are the ones most intimately familiar with the technology at the core of the next wave of commercial deployments. In other words, while others are still trying to figure out the blueprint of next-generation infrastructure, Huawei will already be building it.

Despite the continued suspicions about the company being a potential IP thief, there’s some reason to think Huawei itself could be a target for cyber espionage, given the vast trove of research it’s assembled. In 2018 it became the world’s fourth-largest R&D spender, investing US$15.3 billion in a year, and it now boasts 96,000 R&D employees globally. In 5G alone, Huawei has spent US$4 billion in the past decade, more than the total invested by its Western rivals combined. Every fifth 5G proposal vetted by the international standards-setting organization is from Huawei, more than any company, according to researcher IPlytics GmbH.

Earlier this year, former Prime Minister Harper was asked in a Fox News interview how Huawei, which now supplies almost every Canadian telecom operator, had managed to penetrate his country so deeply. He said it was because the company had grown too strong and that there weren’t enough Western companies to compete against it, without acknowledging the irony that it was his administration that had allowed Nortel to collapse. “Ultimately, the government of the United States is going to have to work with allies to make sure that there are Western providers of all these equipment and services,” he warned. “Otherwise, the pull toward Huawei will get stronger and stronger.”

BNN Bloomberg is a division of Bell Media, which is owned by BCE.