Apr 29, 2024

Government deficits and their impact on asset markets: Berman

By Larry Berman

Larry Berman takes your questions

The first secretary of the U.S. Treasury (equivalent to Canada’s Minister of Finance) was Alexander Hamilton. He was famous for many things (including a musical), but in my mind, this quote of his is very relevant today: “A national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing." The context was during and following the U.S. Civil War.

Sadly, today, the national debt is predominantly used to buy votes. Debt, when managed prudently, can be an instrumental tool for economic growth and development. By borrowing money, the government can invest in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and other crucial sectors, which ultimately foster productivity and progress. Don’t get me started on Canada’s productivity record under this government and the recent budget. The caveat for all governments (of all parties, to be clear – former U.S. President Donald Trump was a massive offender) is that when times are good, debt should be paid down for a rainy day.

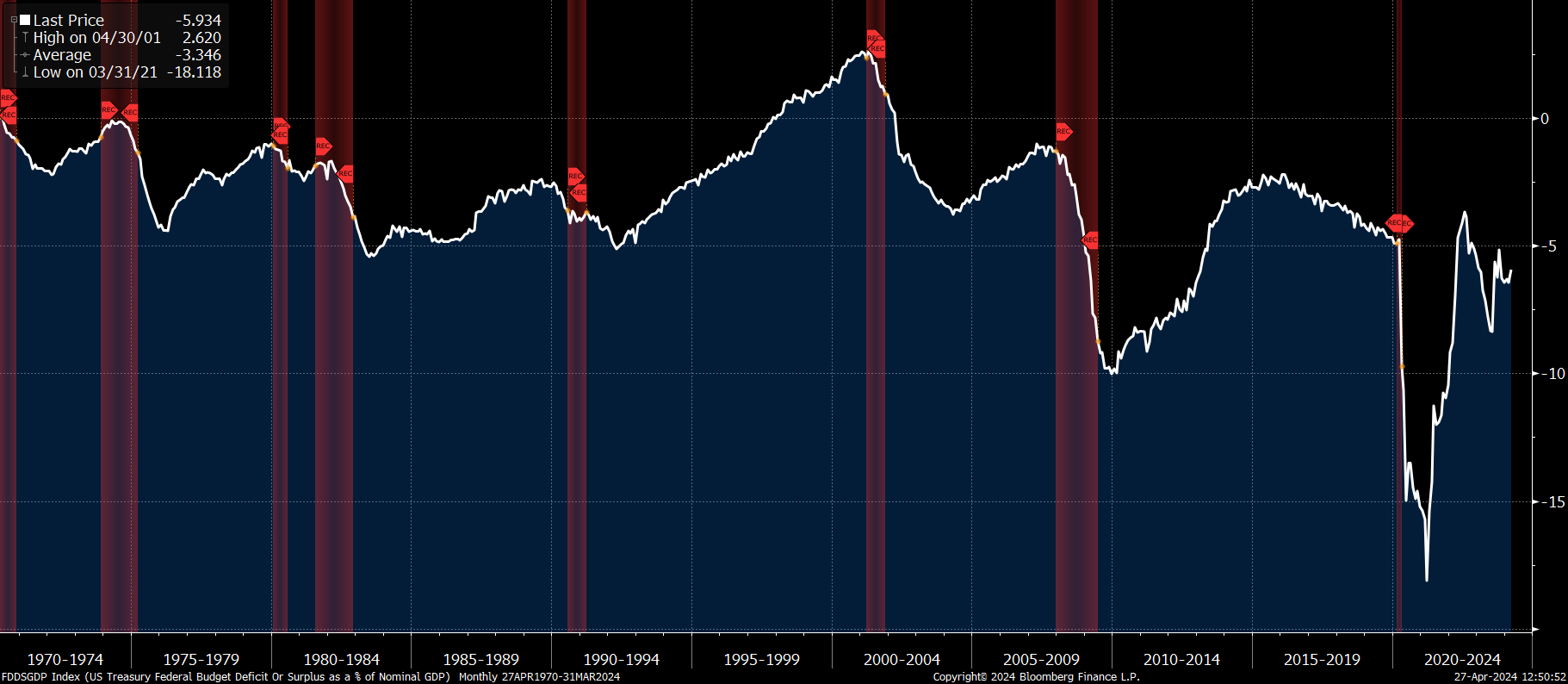

The U.S. government is currently running a deficit (when times are seemingly good at full employment) at six per cent of GDP. Prior to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09 and the pandemic recovery of 2020-21, a six per cent number was never seen, and only came close at the bottom of a recession to help pull the economy out.

We are likely heading into the next recession with an ugly fiscal position and massive deficits to start. To say it mildly, the fiscal outlook is dire. In Canada, it’s relatively better, but it’s not good by any measure.

This week, the U.S. Treasury will announce the funding needed for the next quarter.

The variables are:

- Size of the fiscal deficit

- Runoff of Fed balance sheet (which may include an adjustment for taper)

- Change in the Treasury General Account

- The buyback (buying off the run bonds to add more current coupons)

According to Andy Constan of Damped Spring Advisors, an expert in understanding treasury flows and the impact they have on asset markets, the fiscal deficit “has some potentially significant volatility due to tax receipts and interest expense; the budgetary portion is in gridlock, but, as seen this week, issuance will grow by 6.5 per cent this year due to the Ukraine, Taiwan and Israel aid package.”

“We start with a baseline assumption for the 2024 Fiscal deficit of $1.6TN. In aggregate, we estimate the deficit funding need at $390BN for 2Q24. We see very little chance of a lower need and a fair amount of upside to the number.”

Constan says the key number to look at is the new coupon debt. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen can choose to finance more bills like she did in November, triggering a risk-on rally, but that’s only kicking the can again. His base case ranges between US$475-$675 billion in new debt (we find out the details at 8:30 a.m. on May 1). The gross debt to be financed is about $1.088 trillion. If the headline of net new debt is around $575 billion, the market will see this as neutral and focus on the details on May 1.

Here is a good way of thinking of the impact on assets: Government financing needs to suck money out of the asset markets to fund it (known as the crowding-out effect). The new dollar of financing needs to come from somewhere. Think about it this way: If I have cash in the bank as savings and I buy a new treasury bill, my risk does not change and the money moves from the bank buying the treasury to me. So new debt funded in the money market does not impact risk assets very much at all.

But if that new debt is a 30-year bond, it now carries lots of price risk for 30 years. Thus, the more debt that gets funded with bonds over bills matters a lot. If I’m going to give the government money for 30 years at 4.75 per cent, that’s the best I will get, so I need to think about what else I could invest in for that period. I could buy BNS or any Canadian bank and get a tax-efficient dividend with a higher yield and the potential for growth with about the same price volatility.

So, while I’m guaranteed to get my dollar back when I give it to the government, I assume more risk when giving it to a company. This is known as credit risk or sometimes idiosyncratic risk. That’s why we do not put (or should not put) all our risk money in one company, as great as the record of dividends for Canadian banks has been.

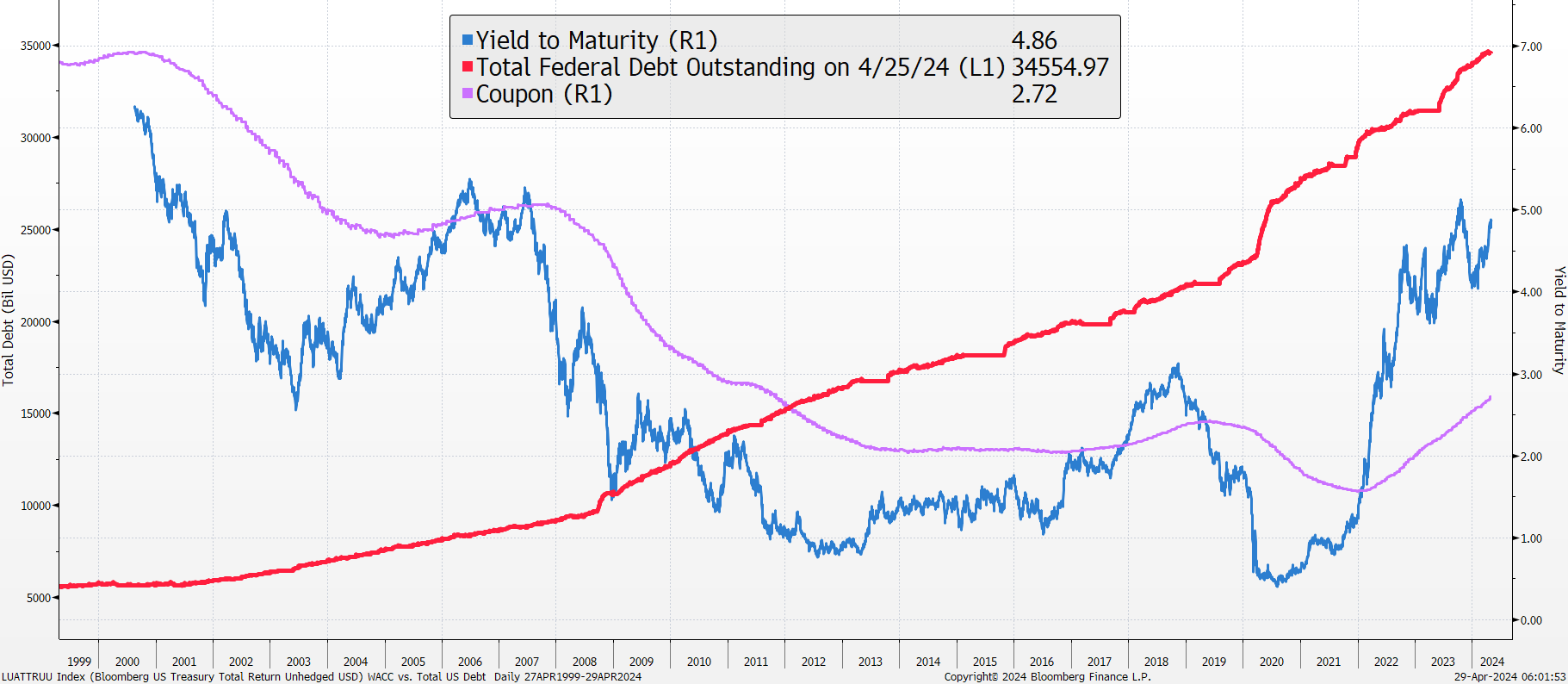

Back to the impact of the supply side of government debt; it’s getting more expensive as part of the deficit on an absolute and relative basis. This chart shows the current yield on all U.S. Treasury debt combined.

The U.S. Federal Debt Outstanding is about $34.5 trillion and growing rapidly. They will never pay this off given the current demographics. Politicians and government officials will lie to us about it, but they also aren’t likely to get elected if they try and fix it. In the U.S., it is projected that the interest cost on the national debt will surpass $1 trillion annually this fiscal year.

This will negatively impact all asset markets eventually. We just do not know when, so don’t let it keep you up at night. A vote for fiscal prudence is about all we can do.

The crowding-out effect will likely have a major negative impact on asset prices and it looks to keep getting worse. U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and others have warned about this recently, but few seem to care or be willing to address it – it’s political dynamite.

Follow Larry:

- YouTube: LarryBermanOfficial

- Twitter: @LarryBermanETF

- LinkedIn: LarryBerman

- www.etfcm.com

- www.qwealth.com