Jun 21, 2021

Millennials, Costco is calling you

, Bloomberg News

Inflation making it unattainable for millennials to get into the housing market: Oakwyn Realty's Saretsky

I remember my very first time walking into a Costco store. I was curious but also a little bemused by the displays, and I didn’t know quite what to make of the throngs of oversize shopping carts that had formed around a table of sweatpants. As a kid, I went on trips with my mom to our local BJ’s Wholesale Club, but this wasn’t the same. On top of that, years of carless, walk-up-apartment living in New York had altered my idea of what shopping was. Many suburban Americans swore by Costco, but I just didn’t get it. Why were diamond rings placed next to packages of sunscreen? And who is buying this many pickles? It was like standing in the center of Disney World during spring break, except instead of kids flocking to costumed characters, very eager grownup customers had swarmed a Costco worker offering samples of pot stickers.

It wasn’t long before I, too, began buying the sweatpants, the sunscreen, the pickles and the pot stickers.

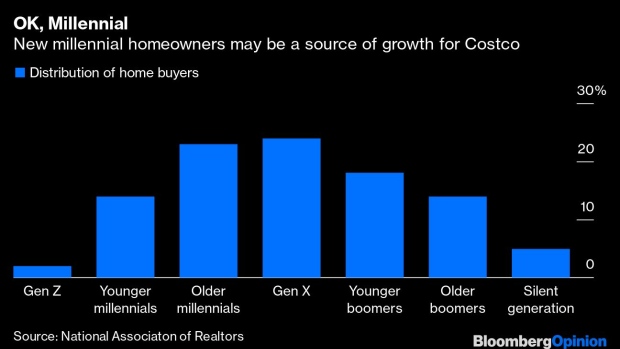

Whether it was my move to the suburbs that inspired my appreciation for Costco or the other way around is a real chicken-and-two-dozen-pack-of-eggs question. For the more than two million other Americans who became first-time homebuyers last year — especially the large numbers of millennials for whom low interest rates and remote-work flexibility made homeownership attainable — a Costco Wholesale Corp. membership might be their next addition. The Costco team, led by CEO Craig Jelinek, has done everything it can to make it a necessity. And its success at doing so has been a boon for the company and its shareholders.

During lockdowns, Costco management made sure stores had the ultimate quarantine, housing-bubble shopping list: exercise bikes, pool tables, extra-large television sets, Philips Hue color-changing smart bulbs. Now, it’s on to the summer reopening must-haves: kayaks, fire pits and string lights. “We’re getting our good share of younger people,” Chief Financial Officer Richard Galanti told listeners of last month’s earnings call. “Historically, that was sometimes a concern of some on Wall Street. Is this for the older generation?”

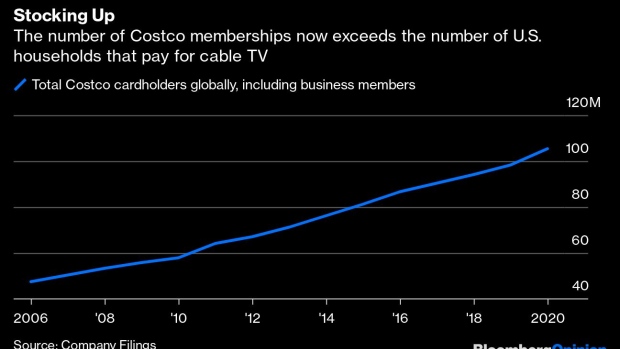

Wall Street couldn’t have been too concerned, though. In 2019, Costco’s stock had its best year since 1998, rising 44 per cent. Its total return for 2020 wasn’t far behind at 33 per cent. The average analyst estimate calls for a more modest gain this year — understandably, considering the company is already valued at 19 times forward Ebitda, a substantial premium to Walmart Inc. and Target Corp.

Retailers up and down the shopping plaza — from Gap Inc. to Walmart — are tripping over themselves to find ways to take back some of the younger-skewing online crowd betrothed to Amazon.com Inc., which kicked off its annual Prime Day sale on Monday. Costco, meanwhile, has kept things somewhat old school and that’s been fine. Click-and-collect, for example, was a successful strategy for many retailers during the pandemic in trying to bring back customers who are either virus-wary or just not wanting to get out of their cars. But where Costco has tested curbside pickup in New Mexico, it “has not set the world on fire,” Galanti said. As it turns out, Costco shoppers actually want to come inside its stores. The treasure-hunt experience overrides convenience, no matter how hard Amazon culture tries to re-calibrate that thinking. You go in for a rotisserie chicken and come out with a new garden-hose nozzle, an ergonomic desk chair and a coconut Keto snack you’ve never heard of. The perception the company has earned is that if Costco sells it, it must be good quality — and if not, returns are easy.

This month, Costco brought back its beloved food samples. I happened to be there for their post-pandemic inaugural appearance: three sea-salt Veggie Straws wrapped in plastic (a new COVID-19 safety feature). Other samples have tended to be brands that would seem to target a certain type of millennial. It’s evident that the proportion of healthy or, let’s face it, healthy-sounding items and vegan choices has increased. That’s expected of most grocers by now, but less so for a bulk-buying warehouse where the variety of options is meant to be limited. In the frigid dairy cave, regular milk sits beside its popular alternatives, Planet Oat and Silk Almondmilk. A baker might also be surprised to find bags of almond flour.

The big draw is Costco’s private-label brand Kirkland, which can be found on everything from jars of minced garlic to 1.75-liters of vodka. Even Warren Buffett is in awe. Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is the largest shareholder of Kirkland competitor Kraft Heinz Co. and he told his audience this at the 2019 Berkshire meeting:

Heinz has been around for 150 years. And here’s somebody like Costco, establishes a brand called Kirkland and it’s doing US$39 billion, more than virtually any food company. Kirkland does more business than Coca-Cola does.

Executives were asked last month if there has been a “sharp increase in the value of a Costco membership,” the insinuation being: Is it time to raise the annual fee? By way of an answer, Galanti pointed to a somewhat unmemorable deal the company struck on March 17, 2020, just as the country was going into pandemic lockdowns. For US$1 billion, it acquired Innovel Solutions, a service that for decades ran deliveries and installations of big appliances for Sears Holdings Corp.; it’s now called Costco Logistics. Costco said that the US$50 million it sold in large household items through its physical store stores just five years ago grew to US$750 million in the year before COVID-19 hit. Now, in theory, a customer could almost furnish their entire house through Costco, presumably making a membership that much more indispensable.

This June marks four years since the last membership fee increase, making June 2022 a pretty good estimate for the next. The renewal rate last year was 91 per cent. Count me in.