Jun 10, 2018

OPEC Haves Can Overpower the Have-Nots in Vienna

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- OPEC and its friends can be divided up in many ways, but the most useful in the current environment is the "haves" and the "have nots."

The first group consists of Russia, Saudi Arabia and the other countries of the Arabian Peninsula, who have the spare capacity to raise production if they wish. The rest fall into the other camp, with little, or no, ability to raise production.

Why does this matter? Because Saudi Arabia and Russia are trying to assemble support for lifting the group's output. They will likely find some allies, but face opposition led by Iran and Venezuela.

This means OPEC's June 22 meeting is likely to be stormy. Both Venezuela and Iran have written to the group urging unity against external sanctions, citing Article 2 of its statute, something I identified last week as potentially driving negotiations. Their move is unlikely to sway Saudi Arabia, which is facing growing U.S. pressure for a million-barrel-a-day increase in supply, or Russia, where the oil industry is urging restraint to be eased.

If anything gets agreed at all it may simply be to maintain the current deal on paper while committing to ensure adequate supply to the market – that would be vague enough to cover just about any eventuality without directly addressing any of them.

OPEC is already forecasting a big global oil deficit for the second half of 2018. This assumes that the group continues to produce as much oil as it did last month. But if supply from Venezuela and Iran falls that deficit will get even bigger. Though Russia and the Arabian Peninsula should be able to make up the shortfall, doing so would undoubtedly stoke tensions in the Middle East and simultaneously reduce the spare capacity available to counter any further disruption to supply.

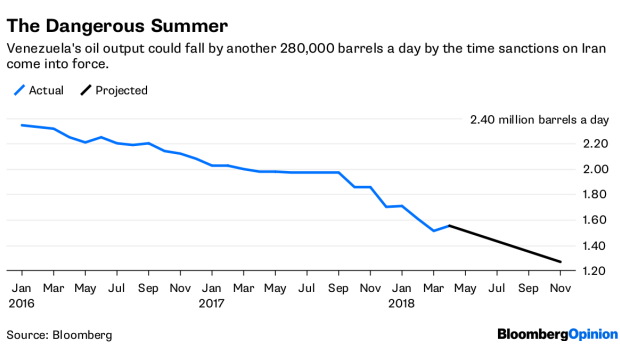

Venezuela's output will fall further in the coming months. While President Nicolas Maduro declares the country could boost output if OPEC relaxes output cuts, the truth is that output is well below the target level it agreed in 2016 and the state oil company may be considering a declaration of force majeure on some of its oil supply contracts this month, according to Argus. The International Energy Agency said capacity could fall by several hundred thousand barrels a day by the end of the year.

The outlook for Iranian production is even worse. There is still no clarity from U.S. authorities on how much buyers must cut their purchases of Iranian crude in order to secure waivers from sanctions. While they are maintaining volumes for now, refiners in Europe appear to be taking a cautious approach for the future. Trafigura Group Pte. warned last week that the market impact could eventually be much bigger than many people are expecting, with problems already emerging on the availability of freight insurance for Iranian cargoes.

President Donald Trump's sanctions on Iran will target condensate as well as crude sales, unlike those imposed by his predecessor, and his required reductions will almost certainly be more than the 20 percent every six months that satisfied the Obama administration. Even a conservative estimate – that a 25 percent cut will be enough to secure a waiver – would cut Iran's exports by 675,000 barrels a day by the start of November if implemented by all the country's buyers.

How much extra will the "Haves" need to produce just to keep things steady?

Russia, Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula would need to boost their output by 875,000 barrels a day over the next six months just to offset expected declines from Iran and Venezuela and prevent the anticipated second-half shortfall from getting any bigger. If President Trump demands bigger cuts to purchases of Iranian oil, that volume would increase.

That is not an impossible task. Russia's Rosneft has been testing capacity to bring new production into use and believes it can add 100,000 barrels “in just a few days,” according to analysts at Aton LLC. Gazprom PJSC’s oil unit estimates the country has about 500,000 barrels a day of spare production capacity. Saudi Arabia says it has around 1.5 million barrels a day of spare capacity that could be brought into operation within 90 days – but it has never tried to sustain production at that level.

In the end, the "Have-nots" may be powerless to prevent Saudi Arabia and Russia from raising production without them. But doing so would undoubtedly stoke tensions in the Middle East and simultaneously reduce the spare capacity available to counter any disruption to supply.

An acrimonious OPEC meeting that breaks up without agreement may initially send the bearish price signal of an output boost from the "Haves." But the bigger problems that would ultimately ensue would prove bullish as the Iranian sanctions deadline approaches.

To contact the author of this story: Julian Lee at jlee1627@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.