Mar 17, 2022

This Timber Company Sold Millions of Dollars of Useless Carbon Offsets

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Jim Hourdequin is one of the planet’s biggest sellers of carbon offsets—the widely used instruments that are supposed to act as a balm for the rapidly overheating climate. His company earned $53 million from these environmental transactions over the past two years.

But now the 47-year-old timber executive is calling out the entire system, including some of his own projects, as broken and shortchanging the climate. Although critics for years have revealed how carbon markets fail to deliver their intended climate benefits, Hourdequin is likely the first major industry participant to admonish the market from the inside. By speaking out, he says, he hopes he can help repair the flawed system: “We don’t think that forest carbon markets can survive and grow if they do not deliver real climate value.”

As the chief executive officer of privately held Lyme Timber Co., a $1.2 billion investment company in Hanover, N.H., Hourdequin manages 1.5 million acres of U.S. forests (roughly the size of Delaware). Even before the recent boom in timber prices, Lyme generated most of its revenue from chopping down trees. But over the past decade, it began selling credits for the planet-warming carbon that some of its forests soaked up. Today, Lyme sells carbon credits on about 220,000 acres, or 15% of its land.

Forest owners can’t sign up all their trees for carbon payments. Each credit is supposed to represent 1 ton of carbon dioxide that’s been absorbed because of a change in behavior triggered by the promise of carbon payments. So a forest owner might scale back planned timber harvests or plant seedlings on otherwise barren lands. Buyers of the credits (usually large corporations) then subtract those carbon savings from their emissions ledgers, because, in theory, their payments caused this carbon reduction to happen.

On a gray December afternoon, sitting in a café in Berkeley, Calif., where he’s traveled after checking in on some of Lyme’s West Coast operations, Hourdequin inhales a sandwich before expounding on carbon credits. With a thin, wiry build, deep-set blue eyes, and a baseball cap atop his receding, closely cropped brown hair, he looks as if he’d be comfortable trekking for miles through backcountry forests. He perks up when talking about financial models and occasionally slips into the vernacular from his days at Harvard Business School. (“I’m a real stickler for structured analysis,” he likes to explain.)

The problem with carbon markets, he says, is that weak rules have created strong incentives for landowners to develop offset projects that don’t actually change the way forests are managed, and therefore do little to help the climate. Most forest carbon projects, including some from Lyme, fall into this category, Hourdequin says. “I believe in being intellectually honest about it,” he says.

Take Lyme’s first carbon project, which it developed a decade ago in mountains east of Nashville. When the company acquired a huge swath of land there in 2007, it agreed to sell a restrictive easement to the state of Tennessee on almost 5,000 acres. This restriction barred Lyme from doing any timber harvesting, and it protected the habitat of several vulnerable species, including the cerulean warbler, a sky-blue songbird.

When a carbon project developer informed Lyme several years later that it could sell carbon credits on the already protected land, Hourdequin could scarcely believe it. After all, the company had already been compensated to safeguard the forest. It was legally prohibited from cutting any of the trees. Any carbon revenue it received would have zero impact on the atmosphere. “We kind of scratched our heads and said, ‘Really? You can do this?’ ” Hourdequin says.

In fact, they could. And it was quite common. The project was enrolled in California’s carbon market, which requires polluters in the state to shrink their emissions and allows them to purchase offsets—including from out-of-state projects, such as Lyme’s in Tennessee—to achieve some of their reductions. Chevron Corp., which operates several oil fields and refineries in California, purchased more than 20,000 of Lyme’s Tennessee credits to meet its requirements. This means some of Chevron’s pollution cuts are, in fact, fictitious. (Chevron declined to comment.)

The brisk sales of meaningless offsets is leading to widespread claims of climate progress that isn’t actually happening. As Bloomberg Green previously reported, environmental groups such as the Nature Conservancy and the National Audubon Society have sold credits for protecting trees that weren’t in danger of being harvested, leading to misleading claims of emissions reductions by Walt Disney Co., JPMorgan Chase & Co., and other companies. Meanwhile, North America’s largest carbon reforestation project, GreenTrees, has sold credits for trees that were already planted through government programs, sometimes more than a decade earlier, resulting in inflated carbon reduction claims by Bank of America Corp. and many others. (The Nature Conservancy, Audubon, and GreenTrees all said their projects followed the market’s rules, while Disney, JPMorgan, and Bank of America each declined to comment.) “There’s a distinct possibility that a great deal of existing carbon offsets are effectively fake,” says Robert Mendelsohn, professor of forest policy and economics at Yale.

Hourdequin isn’t the only one who sees that the market is at a crucial inflection point. Kyle Harrison, who closely tracks carbon offsets as the head of sustainability research for BloombergNEF, a clean energy research group, published a report in January that offered wildly divergent scenarios for offsets. If the market undergoes substantial improvements, delivers higher-quality projects, and fetches higher prices, it could soar to $190 billion in value by 2030. But the offsets industry could also wither away and die without substantial changes. “The current design of the voluntary carbon market is doomed to fail,” Harrison wrote.

Hourdequin is fully aware that there are downsides to speaking out. By essentially admitting the company has abetted corporate greenwashing and undermined efforts to tackle climate change, he exposes Lyme to criticism and risks losing business from offset buyers, who may prefer to purchase credits from forest owners who stubbornly insist their projects are exemplary.

“The spouting whale gets the harpoon,” Hourdequin acknowledges. But he says a transformation can’t happen without an honest self-appraisal. His hope is that the market will tighten its rules and force landowners to change their behavior so they can deliver true carbon savings. If this happens, he expects carbon prices to soar and companies such as Lyme to start managing forests for the value of carbon as much as they do for timber.

“I want carbon offsets to be respected as a solution,” Hourdequin says. “The future of this market is going to be about behavior change. We’re all going to have to design projects that are going to actually change practices and remove CO₂ from the air.”

As an undergrad at Dartmouth College, Hourdequin spent a lot of time beneath the canopies of forests. He studied ecology and evolutionary biology and spent several summers building trails in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. When it came time to write his senior thesis, he examined how young stands of northern spruce fir regenerate. After college he started a logging company with two partners. “Cutting up trees with chainsaws and actually managing forests was a much more exciting endeavor than research,” he says.

Hourdequin joined Lyme after finishing business school in 2005, and he took over as CEO in 2016. When the company began exploring its first carbon deal in Tennessee a decade ago, the market was in its infancy. And in some ways, the requirements seemed daunting. For the next century, Lyme would need to pay tens of thousands of dollars every six years to have foresters come and measure a sampling of its trees to quantify how much carbon was being locked away. If Lyme ever sold the property, the requirements of the offsets deal would transfer to the new owner.

Hourdequin had no clue if these added obligations would torpedo the land’s value. “We were basically scared out of our minds,” he says.

He rationalized the project’s lack of climate benefits as a necessary first step. “People thought these were the things that were needed to get this market started,” Hourdequin says. “You’ve got to make it an easy win for the landowner to sign up for a 100-year obligation. Nobody really knew what they were getting into.”

Lyme began developing a string of carbon projects. But Hourdequin was struck by how often they received large volumes of lucrative credits for creating few additional climate benefits.

One deal netted Lyme about $20 million for minor changes to a forest in West Virginia. After purchasing a huge hardwood forest there in 2017, it put together a carbon project on 47,000 acres of forbidding terrain. Some of the land is so rugged and steep, Hourdequin says, the trees can be extracted only by helicopter, which is prohibitively expensive.

Nonetheless, California’s carbon market would pay Lyme handsomely to preserve these little-threatened trees. To entice landowners with richly stocked forests, California gives valuable upfront credits for these bigger-than-average trees. The landowner must then preserve this larger volume for a century—seemingly a win for the climate.

For Lyme, though, $20 million wasn’t necessary to maintain this higher volume of trees, because it didn’t make economic sense to cut them. “Society probably didn’t need to pay us for that,” Hourdequin says.

Lyme has since scaled back some of its harvests in West Virginia to collect higher annual carbon payments, which could help the atmosphere. But in total, the company has received credits for the property that vastly exceed the climate benefits.

Pacific Gas & Electric, Chevron, and PBF Energy, a petroleum refiner, have all purchased hundreds of thousands of credits from this West Virginia project to meet California’s emission requirements. (PG&E and PBF also both declined to comment.)

Although the project has been a dud for the climate, Hourdequin strongly denies that Lyme is a profiteer. Even carbon projects with scant climate benefits can be expensive, he says. It costs money to measure the trees, and the carbon rules limit a company’s ability to sell off or develop parts of the land. Landowners must also apply some of California’s more stringent forestry rules to their carbon acreage, which can mean less fertilizer and smaller clear-cuts. These rules stick with the land for a century and lower its value. With carbon prices hovering around $10 to $13 per ton, Hourdequin says, the payments are far too low to cover both this lost value and any changes to how Lyme would manage its forests.

To get around these challenges, a budding industry of carbon project developers has worked shoulder to shoulder with landowners, including Lyme, to pinpoint the tracts of land that can generate the largest quantities of carbon credits for the smallest changes to the forest. This tactic deprives the atmosphere—and the public—by finding the biggest payout for the tiniest climate benefit.

Unfortunately the market is now awash in these types of projects, according to Grayson Badgley, who examines offset projects as a research scientist for the nonprofit CarbonPlan. “The way the market is currently constructed, it just does not promote quality,” he says. “The atmosphere gets left holding the bag.”

Last year, Hourdequin began tinkering with a simple idea to fix the market: Instead of looking for forests that can generate lots of offsets with few changes, what if this whole approach was flipped on its head? Start with honest-to-goodness carbon savings by planning to cut fewer trees and see how much it would cost to implement.

Hourdequin and his staff set to work, looking at a half-million acres of Michigan forestland it began acquiring in 2019. The previous owners had aggressively harvested the land. And Lyme was planning on a similar model.

Hourdequin asked: What if Lyme reduced the planned harvest by about 15% per year? His team spent days digging into their forest models and spreadsheets. They calculated that simply implementing the offset project—such as paying for measurement of the trees and restricting their ability to sell small parcels of the land—would cost about $30 per ton. Then the carbon benefits from cutting fewer trees would cost another $30 per ton. All told, it would require $60 per ton to set up an offset project that could have real climate benefits. Could they actually sell credits for that much?

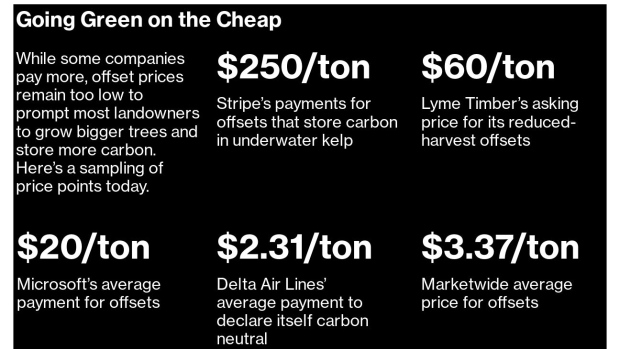

Price signals from the $1 billion trade in offsets aren’t promising. Ecosystem Marketplace, which tracks the industry, reported an average price last year of $3.37 per ton. Some buyers are willing to pay more—Microsoft Corp. says it averages $20 per ton, and Bill Gates spends $600 per ton to neutralize emissions from his private jet—but many others are paying less. Delta Air Lines Inc. declared itself carbon neutral last year after purchasing 13 million offsets at a cost of $30 million, or about $2.31 per ton.

Undaunted, Hourdequin pitched his idea to a forest industry conference in October, with a speech titled “You Get What You Pay For.” He immediately got to the point, telling his audience of fellow forest managers that offsets weren’t delivering on their promise. “It can be argued,” he said, “that carbon markets have paid the landowner to not do what they were not going to do.” He conceded that $60 per ton was “substantially out of market,” but, in effect, he was challenging the industry to raise its standards.

The speech didn’t make waves. A recording on YouTube has garnered only about 100 views. A handful of attendees sent Hourdequin polite messages afterward, expressing agreement.

But carbon market observers hold out hope that a major seller of carbon credits such as Hourdequin could help push the market toward improvement. “Our belief is that transparency is good,” says Matthew Potts, chief science officer at Carbon Direct, which advises companies on carbon reduction strategies. “It’s nice that producers of projects are speaking out.”

Big offset buyers haven’t exactly jumped at Lyme’s new $60 credits. The company pitched its project to a major bank, which Hourdequin won’t identify. The bank declined. Hourdequin then discussed the idea with a couple of large tech companies. One praised his speech and expressed an interest in future collaboration, but both companies have thus far demurred.

Even if Hourdequin were to find buyers at $60 per ton, it’s not clear that Lyme’s new approach to offsets would be good enough. Reducing harvests on working timberlands could cause another landowner somewhere else to cut more trees to fill the demand for lumber, a phenomenon known as “leakage.” Various carbon market rules try to address this by docking the number of credits granted to certain forest projects by anywhere from 10% to 40%. But many experts say the actual leakage rate is much higher.

“If somebody in Topeka wants to build a deck, they’re buying those two-by-fours from somewhere,” says Michael Raynor, a managing director at Deloitte Services LP. (Hourdequin agrees that leakage is a major issue that hasn’t been adequately sorted out, but he says harvest reductions can still have a positive climate impact.)

Lyme isn’t the only outfit exploring different ideas to improve carbon offsets. The Science-Based Targets initiative, considered the gold standard of carbon reduction efforts, published guidance in October that urged companies to limit offsets to projects that actually remove heat-trapping gases from the atmosphere. This kind of project would include new tree plantings and machines that pull CO₂ out of the air. While the initiative is seeking to tighten the pool of credible offsets, it hasn’t yet defined whether projects such as Lyme’s would make the cut. Meanwhile, the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, an initiative launched in 2020 by United Nations climate envoy Mark Carney, recently spun out an integrity council, which says it will produce tools to help assess the credibility of offset projects later this year.

Pachama Inc., a carbon technology company, has been working for two years to write a new carbon protocol, which it says will use satellite data and machine learning to better quantify a project’s true climate benefits. The startup claims this protocol will more accurately compare different types of landowners, closing loopholes used by projects today to inflate the number of credits they receive. Deloitte, meanwhile, is developing types of offset transactions that it says could funnel large sums of money to quality reforestation projects.

It’s too soon to tell whether any of these new initiatives will improve the market. But a key first step, Hourdequin says, is honestly taking stock of how carbon projects have performed. “Ten years into this market, I think it’s fair to be asking whether these projects are delivering climate mitigation,” he says. “If they’re not, it’s fair to begin demanding that they do.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.