Mar 18, 2021

To Zero Out Emissions, Chile Must Rethink Its Forestry Industry

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Patricio Barria spends most days in the thick forests of southern Chile, weaving through narrow roads past pristine blue lakes. From time to time, he pulls over to examine the trees, checking their roots and trunks to make sure they’re growing healthily.

Barria, 53, owns and manages 110 hectares (270 acres) of native woods in the southern region of Los Rios. He runs a firewood business, and also works as a consultant for other landowners to make sure there’s a sustainable balance between growing new trees and cutting down old ones.

“I didn’t just want to be a wood seller, I wanted to use my knowledge to make sure forests are not degraded,” he said. “My clients are medium-sized owners who can afford a private consultant—the big problem is small owners who don’t have the money or the time to wait years for the forest to regrow.”

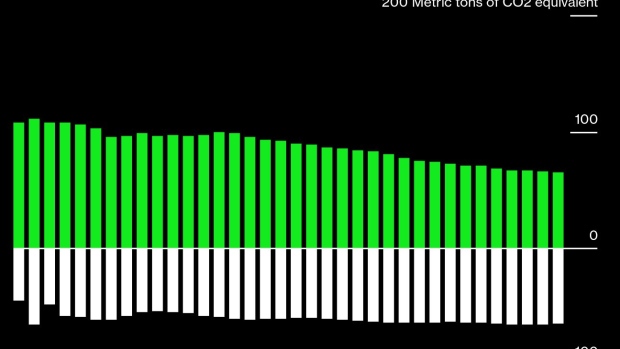

Home to one of the South America’s largest forestry industries, Chile will need more people like Barria if it wants to achieve its target of zeroing out planet-warming greenhouse gases by 2050. The nation is banking on so-called carbon sinks—forests like Barria’s that can absorb more carbon dioxide than they emit—to account for as much as half of its emissions reductions.

“Chile has an unusual situation—we have 17 million hectares of forests that capture and store CO₂,” said Environment Minister Carolina Schmidt. “Achieving carbon neutrality depends on our forestry sector.”

Chile’s announcement last April made it the first South American country to pledge climate neutrality by mid-century. On top of planting trees, it also plans to close all its coal-fired power plants and boost renewable energy to 70% of its energy mix, from just over a quarter last year.

Its roadmap calls for 200,000 hectares of new forests by 2030—covering land twice the size of Hong Kong—of which at least 70,000 hectares will be species native to the area. The government estimates the trees will absorb between 3 and 3.4 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent every year, which is about 3% of Chile’s total emissions.

If Chile implements all its planned policies, it could reach peak emissions by 2023, two years earlier than expected, according to nonprofit Climate Action Tracker. That would make it a global frontrunner in fighting climate change. The big caveat is its outsized reliance on forests to capture carbon. Planting that many trees is an expensive logistical challenge, and there’s no guarantee the trees will be able to absorb as much CO₂ as the government assumes. For this reason, CAT rates Chile’s plan “insufficient.”

Chile isn’t alone. About two thirds of countries in the world list some form of nature-based solution as part of their commitments under the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep average global temperatures from rising more than 1.5°C from pre-industrial levels, according to a February paper by researchers including Nathalie Seddon, director of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative at the University of Oxford. These often, though not always, include initiatives to plant more trees.

Many companies, including oil giants such as Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Eni SpA, also cite nature-based solutions in their net-zero plans. The trend has irked climate scientists, who warn against the temptation to use carbon offsets to replace the hard work of cutting fossil fuels. Buying credits linked to planting trees are often cheaper than implementing structural changes, though there’s little oversight to ensure the programs are helping the climate as much as they claim.

For Chile, trees have been a go-to solution for some time. The nation started subsidizing tree planting in 1931 as a way to reduce soil erosion on the agricultural land its economy relies on. In the past, selling the wood was also seen as a way to help the country diversify away from mining.

Using trees to capture carbon would mean changing traditional practices. Residents have to make sure they only cut down old trees, and plant the right species to replace them. Research has shown that forests need to be sufficiently diverse to be effective carbon sinks. Continual care is needed to ensure the trees survive after they’re planted.

Read More: How Mexico’s Vast Tree-Planting Program Ended Up Encouraging Deforestation

“There is a limit to the carbon that can be stored by newly planted trees,” said Alison Smith, a senior research associate at Oxford who co-authored the paper on nature-based solutions. “This carbon is at risk if trees are harvested or if they die from fire, drought or disease as the climate continues to warm.”

In 2017, Chile suffered the worst wildfires on record, with flames burning more than 570,000 hectares. Researchers estimate that the blazes emitted the equivalent of 90% of the country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, effectively releasing to the atmosphere almost double the amount of CO₂ it emits in an average year. The country has also been hit by severe drought for more than ten years. According to the latest estimates, water availability could be halved in its northern and central regions from 2030 to 2060.

The extreme weather makes it more difficult for trees to mature. “Chile’s is a challenging goal because climate change is pushing in the other direction,” said Andres Pica, executive director of the Global Change Center at Universidad Catolica in Santiago. “There’s less water, more wildfire risk and more degraded forests that emit CO2 instead of capturing it, so wildfires could be larger going forward.”

To mitigate those problems, Chile will have to back up its tree-planting plan with funding. Plantation forests in Chile more than doubled from 1986 to 2011, according to research by Cristian Echeverria, a professor at Universidad de Concepcion, and others published in Nature Sustainability last year. During that period, the government paid out $408 million, an average of $447 per hectare, to plant an area almost three times the size of Rhode Island.

Yet their research found the program didn’t result in a proportional increase in forests’ capacity to act as carbon sinks. Carbon stored in vegetation increased by just under 2% during the period. At the same time, native forests, which are more successful in capturing carbon, shrunk by 13%.

Read More: China’s 40-Year, Billion-Tree Project Is a Lesson for the World

“We only need to look back to realize the importance of differentiating between exotic and native species,” Echeverria said. “Any public policy financing instrument should make that clear to avoid past errors.”

The Chilean government hasn’t said how much it is budgeting for reforestation. In a submission of its renewed net-zero pledge to the United Nations, it acknowledges the challenge of wildfires and commits to improving forest management, although it gives little detail of how it will do that. Reaching carbon neutrality will require investments of $27 billion to $49 billion between 2020 and 2050, according to estimates by the Energy Ministry.

Any financial support for reforestation will have to account for owners of small patches of native forests. At the moment, preserving those areas isn't profitable and most landowners end up cutting down trees such as oaks and giant redwoods and selling the wood.

“Chile’s goal to use forests as carbon sinks is in danger if the wood market is not properly regulated,” said Vicente Rodriguez, who ran Chile’s Corporation of Wood Certification for years. Wood must be certified not just by origin, but by quality as well, she said.

In southern Chile, where forests are abundant and rains fall frequently, residents burn wet wood during the winter to cook and keep warm. That releases more soot than dry wood, increasing Chile’s overall carbon footprint and making towns in the region among the world’s most polluted.

“The carbon neutrality target is a tremendous opportunity to restore our south, our forests that weren’t properly managed and became degraded decades ago,” said Barria, the firewood business owner. “We have the chance to generate new forests—as long as the state makes the necessary investment.”

This article is part of Bloomberg Green’s Carbon Benchmarks series, which analyzes how countries plan to reach net-zero emissions. Click here to get e-mail alerts when new stories are published.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.