Oct 30, 2020

Trudeau's fast track for tech workers hits pandemic roadblock

, Bloomberg News

Justin Trudeau’s fast-track visa program gave Canada an edge over the U.S. in the global race for talent. The pandemic is eroding it, leaving some tech startups and their recruits in limbo.

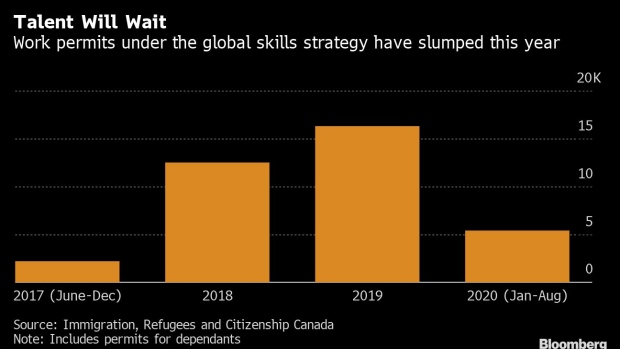

The visa has been used to accelerate the arrival of thousands of software engineers, computer programmers and other professionals since 2017. But the number of people entering Canada this year under the global skills strategy program was down 49% through August, data obtained by Bloomberg show. The government says it’s committed to immigration, but acknowledges COVID-19 has caused delays.

Approvals are now taking months, far from the rapid processing -- as little as two weeks -- that made the visa popular with the tech industry, according to companies with pending requests. The situation is particularly troublesome to Canadian startups, which can’t compete on salaries with global tech giants but could at least count on fast immigration procedures to help them secure new staff.

Higher immigration is a signature policy of Trudeau’s government, which has made welcoming foreigners a cornerstone of Canada’s long-term economic plan. In contrast with the U.S., which keeps making employment-based visas harder to get, Canada has touted an open-arms approach to skilled labor, hoping to make up for years of brain drain to Silicon Valley.

On Friday, Canada said it plans to attract 401,000 permanent residents next year, boosting pre-virus goals by 50,000 to spur economic recovery. The targets, though, assume a return to normal international travels. To help boost the numbers, the government will make it easier for international students and temporary workers already in the country to become permanent residents.

EnPowered Inc., a company in Kitchener, Ontario that provides technology to help users control their electricity costs, is one startup affected. It’s been waiting for most of 2020 to get a work visa for a developer in Nigeria. Approval for a South African cloud engineer is also pending.

“If we can’t get them into Canada, it fundamentally changes how our entire company works,” said Chief Executive Officer Tomas van Stee. “It puts challenges on the whole team.”

EnPowered found the visa program “phenomenal” in the past, said van Stee, who credits it as a major reason for staying in Canada. The company tries to hire locally as much as possible, but expands the search overseas for senior positions requiring rare and “very specific developers skills,” he said.

His case is not isolated. The Council of Canadian Innovators, a tech industry group that plays a referral role in the program, said it’s been hearing from concerned members since March.

“Any immigration delays impact the potential growth of Canadian companies, which is why the fast-tracked visa under the Global Skills Strategy was such an important policy” for young companies, Executive Director Ben Bergen said.

Digital Boom

Companies of all sizes have taken advantage, including the Canadian outposts of foreign firms. French video-game publisher Ubisoft Entertainment SA, Canadian e-commerce giant Shopify Inc. and Royal Bank of Canada were among employers that got authorization to hire foreign workers in the second quarter, a first step in some cases to qualifying for fast processing.

While not immune to the pandemic, Canada’s digital economy has been more insulated from its impact than most, according to the Information and Communications Technology Council, an Ottawa-based research and policy group. From early 2020 to late 2022, it will add 102,000 jobs, the council forecasts.

Foreign workers are keen to take part in that growth, according to Ilya Brotzky, the CEO of Vancouver-based VanHack, an online recruiting platform for tech workers.

About 80 per cent of the jobs offered on the platform are in Canada. Applications are at almost six times January levels, Brotzky said. But work permits, which VanHack also assists with, are trickling in at a slow pace. Authorization from labor and immigration authorities used to take four to six weeks. It’s now four to six months or longer, he said.

“Before, we were getting them approved quickly. Now we don’t really have a timeline, we just submit it and hope it will be approved,” he said. “Canada is losing tax revenue and economic stimulus.”

The government has continued to process permanent and temporary immigration requests during the pandemic, though timelines have been delayed as some application centers temporarily closed, according to Alexander Cohen, a spokesman for Immigration Minister Marco Mendicino.

The department’s priorities shifted because of the virus. Immigration officials focused on applicants who were workers in essential services and eased visa procedures for workers already in Canada who lost their job and found a new one. Permits under the global skills program, while also a priority, may take longer than they used to, Cohen said.

“Immigration is essential to getting us through the pandemic, but also to our short-term economic recovery and our long-term economic growth,” Mendicino said during a press conference Friday.

Eroding Advantage

Admissions of permanent residents in the first eight months of the year reached 128,430, or about 38 per cent of 2020 targets, while the number of student visas in August was just 36 per cent of last year’s levels.

Myant Inc., a Toronto company that’s developed a technology to knit sensors into textile and use garments to monitor people’s health, got caught in the slump.

It’s been hard to find programmers who also have experience in textile, and the company recruited several employees from Bangladesh, India and the U.S. relatively painlessly in the past. This time, bringing an Italian knitting technician and programmer proved more difficult, Executive Vice President Ilaria Varoli said.

“We started this process of getting him a visa in June, we literally expected a few weeks,” she said. It finally came in October.

Because Myant makes a physical product, it was hard for its new recruit to contribute fully from afar. But as more tech companies say they’ll let employees work remotely, the country they’re based in may become less relevant -- chipping away at Canada’s visa advantage.

The new situation is set to intensify global competition for the best workers, according to Jean Le Bouthillier, CEO of Quebec City-based Qohash Inc., which sells data protection technology to companies like banks.

Le Bouthillier experienced it first hand. Two candidates he recently interviewed ended up taking better paid offers from U.S.-based companies, without having to leave Canada. “We all understand that a major change took place in the world,” he said. “It’s going to have consequences on workers and salaries.”