Sean Pan wanted to be rich, and his day job as an aeronautical engineer wasn’t cutting it. So at 27 he started a side gig flipping houses in the booming San Francisco Bay Area. He was hooked after making US$300,000 on his first deal. That was two years ago. Now home sales are plunging. One property in Sunnyvale, near Apple Inc.’s (AAPL.O) headquarters, left Pan and his partners with a US$400,000 loss. “I ate it so hard,” he says.

A new crop of flippers, inspired by HGTV reality shows, real estate meetup groups, and get-rich gurus, piled into the market in recent years as rapid price gains helped the last property crash fade from memory. Many newbie investors are encountering their first slowdown and facing losses from houses that take too long to sell. Meanwhile, they face steep payments on a kind of high-interest debt — known as “hard-money” loans — that helped power the boom.

“Flipping only works in an appreciating market where homes move quickly,” says Glen Weinberg, the Denver-based chief operating officer of Fairview Commercial Lending, which is tightening its standards for real estate investors. “Those factors are now in flux, and that’s what’s going to lead to the demise of a lot of flippers.”

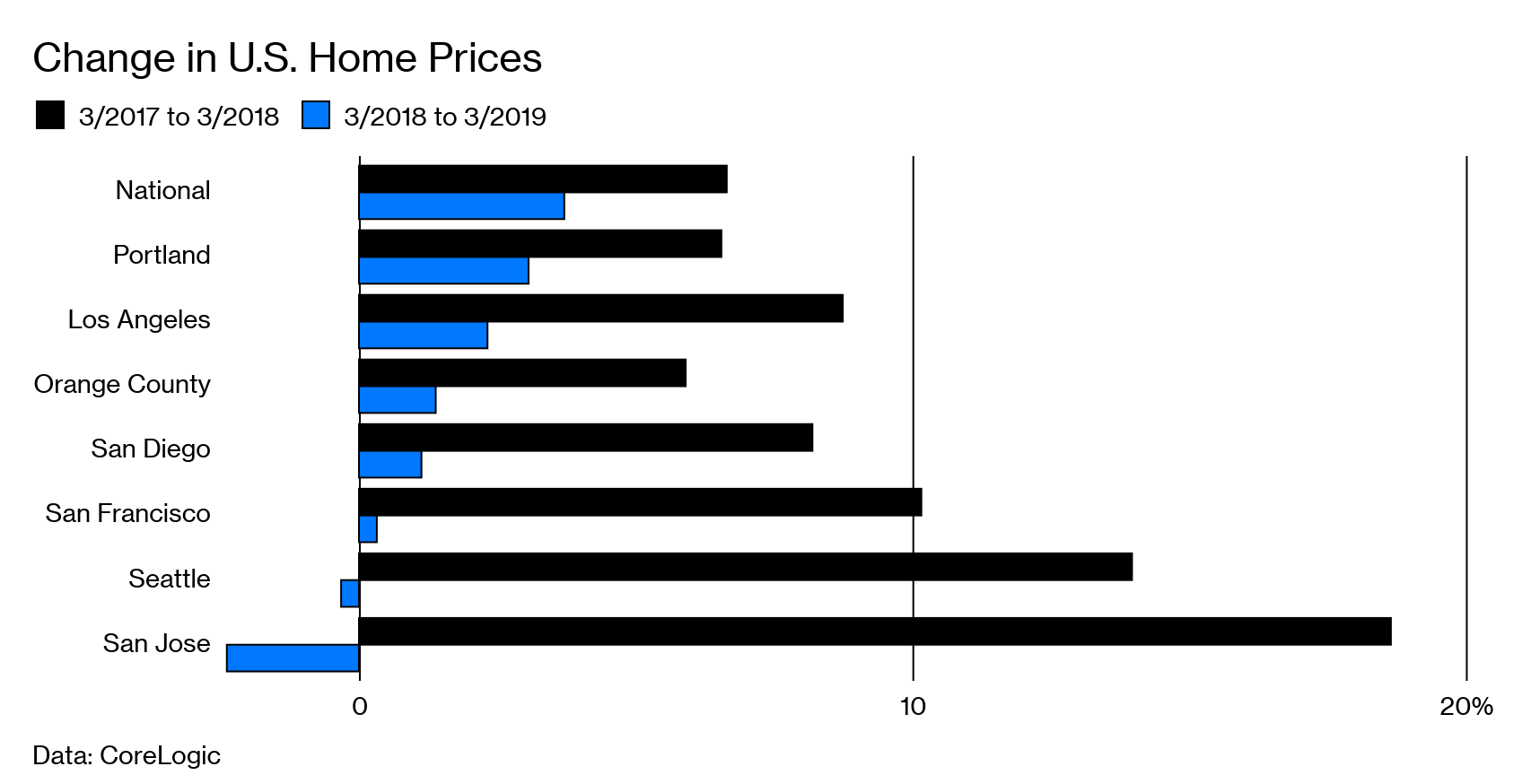

About 6.5 per cent of U.S. sales in the fourth quarter were flips, or homes sold within a year from when they last changed hands. That was the highest share in seasonally-adjusted data going back to 2002, according to real estate data firm CoreLogic. (It’s even higher than during the last boom, when there were more newly built houses for buyers to choose from.) Such deals were particularly attractive in Western markets such as Northern California and Seattle, where prices climbed by double-digit percentages annually. But some areas got too hot, and prices are flattening or falling. Fourth-quarter losses for flippers who sold within a year were the highest since 2009, according to a CoreLogic analysis that looks at buying and holding costs, but not rehab expenses. In the San Jose area, 45 per cent of flips lost money.

Unlike the last decade’s housing crash, in which speculators bought simply to resell, many of today’s flippers sink money into fixing up properties. Their hard-money loans, which come from private investment groups, often have high interest rates and low down payments. The loans also are bigger because renovation costs are folded in.

Large companies including Blackstone Group LP (BX.N) and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (GS.N) have gotten into such lending. Competition has helped drive interest rates on some of the loans below 10 per cent, says Todd Teta, chief product officer at Attom Data Solutions, a real estate tracker. Now lenders “are easing capital requirements and lengthening loan terms because it’s taking longer to flip homes,” Teta says.

Many flippers are professionals who’ve been in the business for years. But the latest boom has also lured people such as Rachelle Boyer in Seattle, who got into property investing after attending a US$25,000 real estate coaching program. The course taught her to think big, stay positive, and never quit. In 2016 she left a six-figure job and started flipping houses. When demand slumped last year, she fell behind on hard-money loan payments for two houses languishing on the market. She has one more to get rid of. “We will get through the dip. Things are already perking up a bit,” Boyer says. Nevertheless, she’s reconsidering the wisdom of reselling rehabs. Her goal now is to buy 25 houses in Pittsburgh, a cheaper, less volatile market, with a strategy of holding on to the properties as rentals.

Weinberg, the Denver hard-money lender, says he’s increasingly selective with borrowers and deals. He requires flippers to put 40 per cent down on a house. But the lenders he competes with are financing purchase and rehab costs with only a small down payment or none at all. The flipper “can go in with no money, his pockets just blowing in the breeze,” he says. “The lenders are going to be left holding the bag.”

The downturn may provide an opportunity by lowering the cost of houses, but buyers have to be able to withstand losses. Bryan Pham, a Bay Area software engineer who also flips houses, has purchased four during the slowdown even as he’s had to put some projects on hold. After the downturn last year, he decided to pay US$47,000 extra in loan extensions so he could keep three homes off the market, waiting for spring demand to kick in. Pham estimates he’ll take a US$50,000 loss on one home that was listed for US$1.1 million and took a month to go under contract. “I’ve seen people make foolish decisions in the past and still make money,” he says. “Now you have to be conservative.”

Pan, the aerospace engineer, is undeterred. He started a blog and podcast about flipping and plans to quit his job to focus on flips full time. He got into property investing after reading Robert Kiyosaki’s financial advice book, Rich Dad, Poor Dad. Pan began scouring online investment forums and attending meetup groups to learn more, but his biggest lesson came last year with the Sunnyvale home. He thought he got a “sweet deal,” negotiating the US$2 million asking price down to less than US$1.8 million. He and his partners decided to go all out on the remodel. The project took longer than expected, and then the market went soft.

Pan couldn’t afford to wait for a rebound. The holding costs alone for three properties he was trying to dump totalled US$30,000 a month. The home sold for less than US$1.7 million, or more than US$80,000 below what he paid for it. “When you buy these houses, you never think you’ll lose money,” he says. “I fixed it up. It should be worth more, but things change.”