May 23, 2022

A 60% Slide in Century Bonds Needs Rollercoaster Math to Explain

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the biggest selloff in decades shook the world’s bond markets this year, some extraordinarily long-dated debt went into free fall, tumbling even more than Wall Street’s usual models predicted.

To Jessica James, a managing director with Commerzbank AG in London, it wasn’t a surprise. In fact, it was validation.

James and her colleagues at the German bank had been using a novel approach to predict the trajectory of bonds with maturities as long as 100 years, relying on math more familiar to rollcoaster designers than financial analysts. Then they watched the scenario they expected play out in real time as, one by one, bonds backed by highly-rated borrowers collapsed like deflated meme stocks.

The price of the University of Oxford’s debt due in 2117 slid 49%. The value of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia’s 2119 bonds was cut in half. And Austria, one of the world’s most highly-rated governments, saw its 2120 debt fall 63%.

“The current conditions of low-starting yields, very long maturities and large yield increases are a perfect storm,” James said in an interview.

Bond markets have recently steadied amid mounting fears about a slowdown in economic growth, a sign that the worst of the rout may be over. But the magnitude of the losses -- and the apparent failure of traditional models to accurately predict them -- illuminates a little-known risk that built up in fixed-income markets during a decade of loose monetary policy.

The bonds had allowed governments to lock in rock-bottom interest rates for decades at a time when inflation was seen largely as a problem of the past. They took off after the global financial crisis of 2008 as central banks held key lending rates close-to-zero or negative, wth Mexico, Peru, Austria, Ireland, Bolivia and Israel among nations that have sold them since 2010.

While the decades-long maturities made the price of the securities highly sensitive to interest rates, that was a draw to buyers because the more rates slid, the bigger the gains were.

But that process has since shifted into reverse as central banks worldwide tighten policy steeply in the face of the most rapid inflation in a generation. And like other novel financial products that proliferated in boom times, they didn’t fare quite as expected during the bust.

Traditional bond-pricing models are based on convexity, or the rate of price changes as a result of duration, a measure of sensitivity to interest rates. Its widespread use was spurred amid the mortgage-bond boom of the 1980s, and it works well for typical debt due within 30 years.

Yet the margin of error turned out to be far larger for extremely long-dated bonds at a time of rapidly rising yields, providing a test for century bonds, a relatively rare type of security before their proliferation over the past decade.

“We are now in an environment where our familiar notions of duration and convexity begin to deceive us,” James said.

James, who earned a doctorate in physics from Oxford, and her Commerzbank colleagues Michael Leister, Christoph Rieger and Hauke Siemssen had been exploring the problem even before this year’s rout.

Last year, they published a paper on a more high-precision analysis of century bonds that relies on third and fourth derivatives of interest-rate risk: the rate of change of convexity, and the rate of change of the rate of change of convexity, respectively. That level of detail is virtually unheard of in finance. Instead, it’s used in fields such as rollercoaster design, which requires engineers to not only look at velocity and acceleration but also third and fourth derivatives called “jerk” and “jounce.”

“It’s important with rollercoasters to minimize jerk and keep acceleration constant, hence coaster loops are teardrop-shaped rather than round,” she said. “They’re a nice analogy with bonds as usually higher terms don’t matter. But they become important in the ‘rollercoaster world’ of changing yields we now live in.”

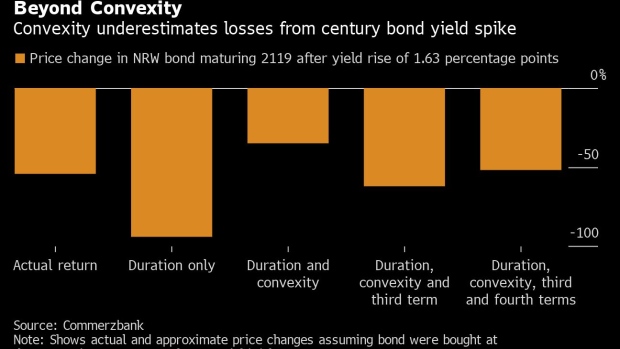

James and her colleagues said their calculations proved far more accurate than more simple models. Looking at duration alone, they found, overestimated the losses. A simple convexity model, on the other hand, underestimated them, projecting that the North Rhine-Westphalia century bond would lose 35% if yields increased around 1.6 percentage points. Using the third and fourth derivatives, however, projects a loss of about 52%. The actual slide was 54%.

James said the level of analysis is currently only relevant for bonds with maturities of 50 years and longer. If debt prices keep sliding enough to drive up the yields on 30-year bonds by four percentage points from their lows -- or around twice the jump the benchmark US Treasury has seen so far -- it will become relevant there, too.

Sovereign debt in Europe saw renewed selling Monday after President Christine Lagarde said the European Central Bank is likely to start raising interest rates in July and bring them above zero by the end of September. US Treasuries also fell, sending the 10-year yield 5 basis points higher to 2.83%.

“The expectations an investor might have from an understanding of duration and convexity become less useful -- even potentially misleading,” James said.

(Updates with Monday’s bond moves.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.