Nov 5, 2019

A Hungarian Scorns the Euro in Quest for More of Them

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Hungarians like the euro: 66% of them support the idea of replacing their forint with it. The rest of the world likes it, too: Global international reserves in the common currency are at the highest level since 2015. So it seems like an odd time for Gyorgy Matolcsy, a governor of the Hungarian Central Bank, to write an op-ed in the Financial Times denouncing the euro as a mistake. Matolcsy’s attack, however, should be seen as a clever provocation rather than as advocacy of the European currency’s abolition.

Matolcsy’s argument is that the creation of the euro was a political decision based on false premises: France’s hope that it would prevent Germany from getting too strong, the idea that it would strengthen the bonds between Europeans in the face of a Warsaw Pact threat, and the European federalist vision of a counterbalance to the U.S. Germany became a dominant force in the European Union, using the exports boost provided by a weak euro. The Soviet bloc fell apart even before the common currency could be introduced. And while European companies never managed to outcompete U.S. ones, especially in tech, the U.S. started considering Europe a competitor anyway, resulting, Matolcsy wrote, in “both open and hidden U.S. warfare against the EU and the euro zone in the past two decades.”

These may all be legitimate historical points. One could also argue — and Matolcsy does, citing a Center for European Policy study published earlier this year — that the euro only benefited a few of its members and that even they failed fully to use it to their advantage.

But criticizing the euro from Hungary is a somewhat pointless exercise. Two-thirds of the country’s exports are to the euro area, and more than 70% of its total foreign trade is invoiced in the common currency, according to the European Central Bank. About 10% of total cash and deposits in Hungary are held in euros — a low rate by eastern European standards, but still quite a significant amount. And Hungary is one of the non-euro countries whose business cycles are the most synchronized with the euro area’s.

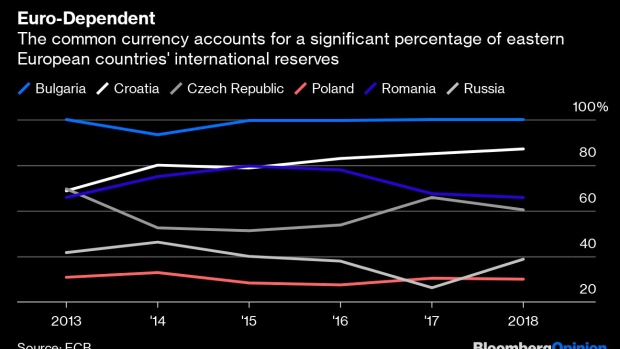

The Hungarian Central Bank doesn’t report the currency composition of its international reserves, but if neighboring countries are any indication, the euro’s share in them is probably higher than the global average of 20%.

The reality of living in a European Union country that doesn’t use the common currency is that the euro’s abolition would be almost as much of a shock as in a euro-zone nation.

It’s no surprise, then, that for all his criticism of the euro as a “mistake” and a “trap,” Matolcsy doesn’t call for it to be abolished. What he suggests instead is a smaller common-currency area. “Members of the euro zone should be allowed to leave the currency zone in the coming decades, and those remaining should build a more sustainable global currency,” he wrote.

Interestingly, in a speech earlier this year, Matolcsy said that Hungary would join the euro “in the coming decades.” It’s not that he has changed his mind: Rather, he sees his country as a potential member of the “more sustainable global currency.” A key to what that means can be found in the FT op-ed:

Two decades after the euro’s launch, most of the necessary pillars of a successful global currency — a common state, a budget covering at least 15-20% of the euro zone’s total gross domestic product, a euro zone finance minister and a ministry to go with the post — are still missing.

Hungary is a major net recipient of EU funds; in 2017, the bloc contributed 2.8% of Hungary’s gross domestic product to the country’s development, mostly in cohesion assistance and agricultural subsidies. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for Hungary, though, if European funding wasn’t coming from an EU budget of less than 1% of the bloc’s GDP but from a pot equaling at least 15% of the euro area’s economic output?

Matolcsy, a former economics minister, is an old ally of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, a nationalist politician who values sovereignty above all else. A national currency, with the crisis-fighting flexibility it’s supposed to provide, is a key element of sovereignty. But more European money — which Orban often uses to reward loyalists — could be an incentive for Hungary to consider joining the common currency.

Economists have pointed out that the European monetary union is incomplete without a common fiscal policy. To eastern European nationalists, that has a special meaning. They only want a common policy that would boost economic convergence between their countries and Europe’s wealthier west. That, of course, is exactly the reason Germany doesn’t want a big common budget.

Matolcsy’s criticism of the euro should be read with all this in mind. If the euro area’s big economies ever decide to move toward a fiscal union, the eastern European common currency holdouts will be eager to jump aboard the gravy train.

To contact the author of this story: Leonid Bershidsky at lbershidsky@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.