Mar 12, 2023

A Lost Decade Worse Than Japan’s Threatens to Change UK Forever

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

As the UK buckles under the strain of anemic growth, strikes, fraying infrastructure and record hospital waiting lists, Jason James thinks back to another economic crisis that dominated an earlier part of his banking career: Japan’s infamous “lost decade.”

James, 58, spent the 1990s working for HSBC Securities in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi financial district. It was a period that suffered a 60% slump in stocks and a collapse in land values that led to zombie banks and an economy overwhelmed by bankruptcies and bad debt.

But his conclusion is that Britain in the 2020s feels worse.

“The system kept working, the trains kept running,” he said. “I don't think you ever had the sense that everything was falling apart in the way you've got here.”

His perception of economic decay is backed by the numbers. Bloomberg analysis of official data and Bank of England forecasts shows UK growth will average 0.8% a year between 2016 — when Britons narrowly voted to leave the European Union — and 2025. That’s below the average 1% in Japan from 1992 to 2001, the “lost decade” often cited amid warnings of “Japanification” whenever a country endures a prolonged slowdown.

Yet that stigma is only part of the problem in the UK, which faces handicaps including soaring inflation that make it a very different economic environment to 1990s Japan.

UK PREVIEW: Hunt’s Budget Will Keep Powder Dry Until Election

Dire productivity, crumbling public services and a worsening labor supply form the backdrop to Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s budget statement on Wednesday, and despite a recent run of stronger-than-expected growth, point to a long-term drag on an economy in which animal spirits are fading. Had the UK maintained the pace of growth it enjoyed before the 2008 global financial crisis, Britons would now have on average about £8,000 ($9,600) more in disposable income. The median salary was £33,000 last year.

The shift down the gears also risks undermining Britain more broadly, from lost dynamism in London to a lack of sway relative to the US, European Union and China on trade and climate change.

It won’t be easily reversed. Japan effectively spent its way out of its asset crash and banking crisis, but after the global financial crisis and the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine, as well as the market turmoil triggered during Liz Truss’s brief premiership, Hunt is likely to reiterate the UK can’t afford to go down the stimulus route again.

It means people who experienced Japan’s stagnation and Britain’s troubles today are likely to continue to see a stark difference.

“Government debt kept rising,” said James, who co-wrote The Political Economy of Japanese Financial Markets in 1999 and is now director general of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation in London. Referring to strikes in the National Health Service and across the UK public sector, he said that in Japan “the hospitals and the ambulances and so on were still operating. In that sense, society kept working and keeps working even now.”

Missing Out

In reality, it's already been more than a decade of sub-par growth for the UK. The country's last really vigorous expansion began in the 1990s when Japan was still grappling with a banking crisis. Under the Labour government of Tony Blair, which came to power in 1997, Britain extended a stretch of economic growth that would last for 47 consecutive quarters and then Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown promised that “boom and bust” economic cycles were a thing of the past.

Instead, the euphoria fed into the global financial crisis, and the collapse of Northern Rock Plc and bailout of other banks put the UK on a different trajectory. The UK has been treading water, initially due to poor productivity and the impact of government spending cuts, compounded by labor supply issues due to Brexit and the pandemic.

UK Wargames a Crash Worse Than Covid If Chip Supplies Shut Off

The Bank of England doesn’t expect the picture to improve, at least during its current forecast period. It judged in February that potential growth — the economy’s speed limit before activity generates excess inflation — will weaken to just 0.7% in 2024 and 2025, a sharp slowdown from 1.7% in the 2010s and 2.7% between 1997-2007.

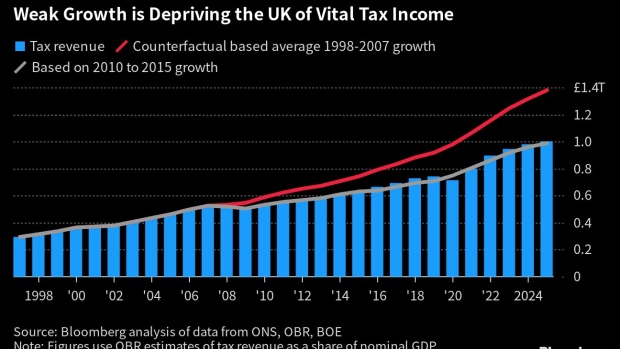

Slower growth, and the poor productivity underlying it, are adding up to huge amounts of lost output. The difference between the pre-financial crisis 2.7% average growth from 1998 to 2007 and the current “lost decade” equates to about £800 billion in lost GDP, and £300 billion a year in lost tax receipts.

Using more modest growth figures, the average 2.1% from 2010 to 2015, the comparison reveals about £250 billion of lost output. Had that growth trend continued, the average Briton would have about £2,400 more in disposable income.

“The difference between, say, 2% productivity growth and 0.7% productivity growth doesn’t seem very big if you look at it in isolation. But these things accumulate,” said Kevin Loane, senior economist at Fathom Consulting. “Over time, governments and citizens face fewer choices. Climate versus health or education versus war. So really, this is the defining economic challenge of our time.”

Growing Pains

The struggle to get Britain growing has become a political obsession, especially for the ruling Conservatives, who according to polls face a trouncing from voters having overseen a period of national decline. One Tory MP, who asked not to be named, said the party’s focus on Europe and pursuit of Brexit meant it had effectively squandered 13 years in office.

London’s Investment Appeal Is Unraveling as Arm Heads to the US

The UK is the only Group of Seven economy that is still smaller than before the pandemic and appeared to be singled out when the International Monetary Fund handed it one of the biggest downgrades in its latest forecasts. According to EY’s latest annual attractiveness survey, France has taken Britain’s crown as the top destination for foreign investment in Europe, in terms of projects. France also overtook the UK to become Europe’s biggest stock market last year, and London is grappling with companies including Arm Ltd. and CRH Plc opting to list in the US instead.

For Chris Scicluna, an ex-Treasury official who covered Japan during the 1997 Asian financial crisis and now heads economic research at Daiwa Capital Markets in London, it’s the lack of investment — as well as the strikes and overall feeling that things aren’t working in the UK — that stand out. Just getting on a train underscores the difference, he said.

Japanese infrastructure “was good and still is good,” he said. “You sense that you're in an affluent economy, which again is not something necessarily you get in this country anymore.”

Officials in Tokyo responded to stagnation and deflation with huge stimulus, which ultimately made Japan the world’s most indebted country as a share of output at the end of the 1990s, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

But after Truss’s premiership unraveled at least in part because traders recoiled at the scale of tax cuts in her “growth plan,” her successor, Rishi Sunak, and Hunt have made putting the public finances on a sustainable footing their priority.

Slow Decline

Still, despite her dramatic demise, Truss’s warning that the UK faces a managed decline without a dramatic change of course is gaining traction across Westminster, including in the opposition Labour Party.

“We need growth, and all the main parties are coming forward with plans,” said Andy Haldane, a former chief economist at the Bank of England, who worked on the government’s industrial strategy and policy to “level up” poorer areas of the UK. But he said more details are needed on how to meet the goal of closing regional disparities and revitalizing industry.

A major problem is that what many economists say the UK must do to get back on track — watering down Brexit rules that stifled trade with the EU, planning reforms and more migration — is politically difficult. Double-digit inflation also means monetary policy is stuck on a restrictive setting as the Bank of England seeks to constrain demand.

But the immediate issue is the government is stuck firmly in firefighting mode. Amid fierce pressure from the bond markets in the fall, Hunt penciled in major spending restraints and tax rises in a belt-tightening that has been dubbed “austerity 2.0,” after the Conservative-led government dramatically cut spending when they came to power in 2010. It’s a legacy the Tories — and the country — have yet to shake off.

UK Braces for ‘Austerity on Steroids’ With Little Left to Cut

The chancellor left himself just £9 billion of headroom against his fiscal rules and is unlikely to have much more to play with on Wednesday. A long list of expensive demands — including a likely extension of current levels of household energy support — leave little room for growth-enhancing policies such as more funding for childcare.

Grand ambitions including a planned high-speed rail link from London to northern England have already been scaled back due to costs, undermining the key Conservative “leveling up” agenda. The government is trying to end labor disputes from nurses to teachers, and more than 7 million people are on a waiting list for routine NHS health care.

“It's not just what's happened in the economy, it's what's happened for social welfare, the NHS, education,” said Janet Hunter, a professor of Japanese economic history at the London School of Economics who lived there in the 1990s. “You do feel in this country there are so many aspects of it that seem to be falling apart.”

--With assistance from Chris Miller.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.