Aug 4, 2020

A Niche Grows in Research: More Firms Pay for Their Own Analyst

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In the incredible shrinking world of brokerage research, one niche is holding up: the one where companies pay directly for analyst commentary.

Dismissing conflict of interest concerns, even global institutions like Exane BNP Paribas are expanding a service that charges firms to be analyzed. That turns the traditional model, where trading customers underwrite the service, on its head.

With demand growing, the purveyors of what’s known as “sponsored research” reject critics who say they’re doing little more than selling advertising. In their view, companies funding analysts is no worse than the practice that has descended through the decades in equity research and is routine for credit-rating firms.

“A reader of the research will know that this is a contractual obligation between company and the research provider and there’s a flat fee and it’s completely transparent,” says Neil Shah, director of research at London-based Edison Group, which has 50 analysts who produce about 40 reports a week. “Whereas you have no idea about the money being generated behind a research note; potentially there’s a banking transaction behind it.”

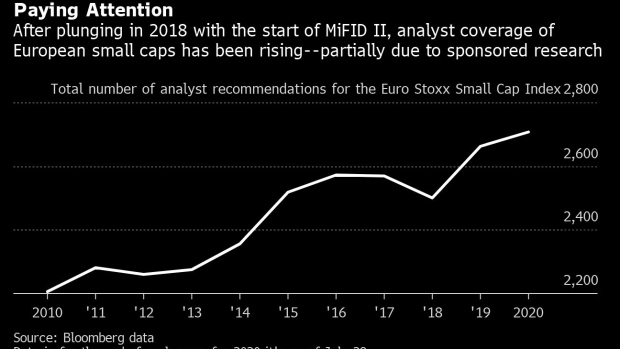

The boomlet has been driven by smaller companies that are typically ignored by sell-side analysts and yet face an urgent need to reach investors. It’s fallout from the 2018 European Union rules that separate research costs from trading fees. Such “unbundling” removed an incentive for analysts to produce research on smaller stocks.

Recognizing the impact, the EU has begun planning to roll back those regulations that were mandated by the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II for companies with a market value of less than 1 billion euros ($1.2 billion).

“It’s too little and too late,” said Andrea Vismara, chief executive officer of Italy’s Equita Group, which offers both sponsored and traditional research. “I strongly doubt that removing unbundling for smaller companies will have any meaningful impact.”

That’s why firms like Edison Group, which has 400 clients paying for their own research, expect the good times keep rolling. While this year should be flat, the business has been growing about 10% annually, according to Shah.

Help Wanted

Likewise, Bryan, Garnier & Co. is hiring health-care analysts, who work on both traditional and company-sponsored research. Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB, or SEB, now has about 60 analysts who do both and has added about 20 companies to its sponsored research coverage since 2018. Kepler Cheuvreux, a French brokerage, has increased the number of such clients to 125 from 60 at the start of 2018.

Data from French market regulator AMF, which tracks the sector, showed 368 sponsored-research contracts in France as of June 2019, up 27% in two years.

About 80% of French companies with a market value below 500 million euros paid for financial research last year, compared with 60% in 2018, according to a survey by Cliff, the French investor-relations society.

It’s “a good opportunity for us to highlight small, higher-quality companies that are not visible in the markets,” said Paul Schneider, deputy head of research at Exane BNP Paribas, which plans to soon roll out the service. At the same time, it’s “very important to have a separate, clearly identifiable product that’ll help investors navigate what’s sponsored research and what isn’t.”

Take Bryan, Garnier’s disclaimer: Sponsored research represents “marketing communication,” where analysts might “have responsibilities to those companies which could conflict with the interests of the clients who receive the research.”

Chris Dyer, director of global equity at Eaton Vance Corp., a U.S. mutual fund company with about $500 billion under management, might be one of those clients. “We would be skeptical of company-sponsored research,” he says. “It would be hard to argue that the research would be truly independent and unbiased.”

Laura Janssens, head of European equities at Berenberg Bank, one of Europe’s biggest mid-cap brokers, says she avoids doing commissioned research because it undermines analyst independence. The Hamburg-based firm has expanded the number of small and mid-cap stocks it covers -- in the classical way -- to about 500 since MiFID II’s introduction as some smaller brokers exited the market.

Against such doubts, the sponsored research firms stand by their work, pointing to the bond market, where Moody’s Investors Service, Fitch Ratings Inc. and S&P Global Ratings are paid by the companies for their credit ratings.

While sponsored-research reports generally eschew recommendations to buy or sell, both SEB and Bryan, Garnier say there’s no difference in the work that their analysts produce on companies that pay for the analysis and those that don’t.

“It’s very important that we don’t separate the two products,” said Nicklas Fharm, head of corporate research at SEB. “For us, everything is just research.”

Edison’s recent sponsored research notes on such companies as Allied Minds Plc, Hellenic Petroleum SA and SUDA Pharmaceuticals Ltd., have disclaimers on the first page and upbeat titles like “A flexible refiner in a turbulent time” and “Improving delivery of existing drug products.” The notes are free on Edison’s website as well as on its LinkedIn page and Edison charges its clients about 50,000 pounds ($65,000) a year for research.

Not all the notes are rosy. While Edison says that the private equity firm Allied Minds is trading at a 62% discount to its net asset value, it also cut Hellenic Petroleum’s valuation by 5% in June to reflect lower global oil demand and industry challenges.

Josina Kamerling, head of regulatory outreach for CFA Institute for the Europe, Middle East, and Africa region, is concerned that some investors may not be able to tell the difference between sponsored and traditional research.

“Who is going to pay for independent and high-quality research if you have free issuer-sponsored research flooding the market,” she said. “You really need to be really experienced to recognize it for what it is.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.