Nov 9, 2022

A Tiny Lab Finds Danger on Drugstore Shelves While the FDA Lags Behind

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- David Light can’t wait to show off his tchotchkes. The curly haired scientist lights up with boyish enthusiasm when he picks up a black coffee mug from the endless array of memorabilia in his office. It’s emblazoned with the trademark lettering of Zantac, the blockbuster heartburn drug. He quickly moves on to a Zantac wine glass from 1983, when the heartburn drug was approved for sale in the US, and then a white and blue Zantac Swiss army knife. A globe, then a t-shirt, next a hat — all stamped with the drug’s branding.

One floor above his office is the lab where groundbreaking Zantac research took place. But Light didn’t create Zantac — he nearly destroyed it. In the process, he’s also become a stand-in, protecting the American public from cancer-causing chemicals in place of a federal regulator that’s failed to do the job.

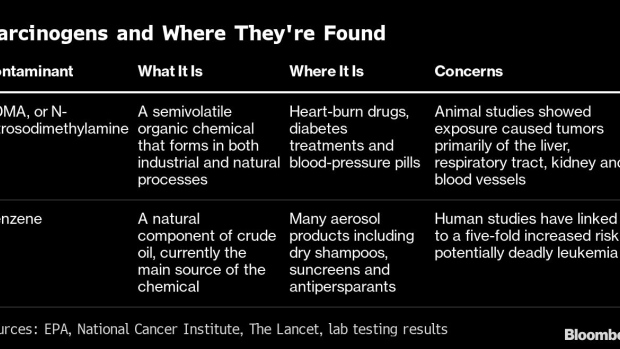

Light is the co-founder and chief executive officer of Valisure, the independent testing lab that first released research showing that Zantac and its generic forms were contaminated with a toxic chemical known to cause cancer. The findings, published in 2019, helped lead to massive recalls and eventual market withdrawal. Some two dozen companies were selling versions of the drug at the time.Valisure truly shot into the public eye last year when it was the first to warn that some widely used hand sanitizers had high levels of carcinogens. Next came the lab’s evidence of leukemia-causing benzene in sunscreens. Then Valisure alerted consumers to dangerous chemicals in spray antiperspirants, and, more recently, dry shampoos. The lab has also warned of contaminants in a popular diabetes treatment. Procter & Gamble Co., Johnson & Johnson, Unilever Plc, CVS Health Corp. and Beiersdorf AG have all issued recalls or halted sales following Valisure’s findings.

In the course of just three years, Valisure’s quest to hunt down cancer-causing chemicals in everyday products has impacted pharmaceuticals and consumer goods in markets worth an estimated $9 billion that touch the lives of tens of millions of Americans.

“I feel that we’ve already saved many lives,” Light said. “When such big numbers of people are exposed, years of exposure with a well-defined carcinogen, there is no doubt there’s unacceptable risk.” On every step of that journey, the Food and Drug Administration, the agency responsible for safeguarding consumers from these problems, has lagged behind the small lab.

Zantac is a case in point.

The drug had been on the market for about 35 years and been taken by millions worldwide — adults with ulcers and heartburn, teenagers with indigestion and even babies suffering from reflux. But it wasn’t a stroke of genius that first led Valisure to test the drug for carcinogens. Concerns over the drug had been raised for more than a decade in academic literature. By the time Valisure started its research on the medication, there had also been some recalls for contaminated blood pressure pills for the same chemical contamination that had already been suspected in Zantac, adding to the urgency.

The FDA sets minimum testing standards drug companies must follow and relies on those manufacturers to ensure their products are safe, Audra Harrison, a spokeswoman for the agency said. Once a problem with a product arises, the FDA “works swiftly to protect the public from potential harm,” she said. The agency has also released guidance to help drugmakers navigate new contamination issues in the last few years. While the FDA views its oversight of drugs, including products like sunscreen and antiperspirant, as robust, Harrison said Congress hasn't updated the agency's ability to oversee cosmetics, such as dry shampoo, “despite rapid expansion and innovation in the industry.”

“The FDA’s highest priority is protecting public health and keeping unsafe products out of the US market,” she said. “Manufacturers are responsible for preventing unacceptable impurities and contaminants in their products.”

Impurity Testing

The testing done by Valisure is routine and can be run by any company that makes pharmaceuticals. On a recent visit, a scientist in a white lab coat replicated the experiment on an older version of Zantac at Valisure’s lab in Connecticut. A vial of milky pink liquid disappears into a machine that costs more than some luxury cars. The liquid is vaporized and separated into its various components. After several minutes, there’s a readout on a nearby computer screen: There’s a tall peak, like an irregular rhythm on a heartrate monitor. The figure indicates high impurity levels.

Valisure first released its Zantac findings to the public in September 2019. It took roughly seven months for the FDA to finally force the drugmakers to pull Zantac products off the market.

GSK Plc, the creator and original seller of Zantac, maintains that there is “no consistent or reliable evidence” the drug “increases the risk for any type of cancer,” the company said in an emailed statement. Sanofi, the most recent seller of the non-prescription version of the drug, said it “stands by the safety of the medicine today.”

Powerful Regulator

As problems with carcinogen-laden medications and consumer products continue to fall through the cracks, the FDA maintains it is up to companies to ensure their products are safe. The situation highlights one of the biggest challenges at the agency: It doesn’t conduct much testing for these types of contaminants.

“FDA doesn’t do routine testing,” said Scott Knoer, who served as the CEO of the American Pharmacists Association for two years before stepping down in June.

“I had always believed anything in the US was safe,” Knoer said. “It was not as thorough as I guess previous perception was.”

The FDA takes a risk-based approach to quality testing, said Harrison, the agency spokeswoman. Each year it focuses on analyzing a few dozen products with already known issues. For example, the agency tested many hand sanitizers in the year that ended Sept. 30, 2021.

Pharmaceutical Fees

The FDA has an enormous purview, overseeing not just food and drugs, but also medical devices, tobacco and cosmetics. Despite that, its budget is just half that of the Environmental Protection Agency or the Internal Revenue Service. And about two-thirds of the funding the FDA receives for its drug activities comes from user fees paid by pharmaceutical companies. Since the early 1990s, the FDA and drugmakers have negotiated a deal every five years that Congress then approves. That agreement between the FDA and drugmakers dictates what the FDA can then do with those user fees.

It costs a drug company more than $3 million in fees to submit a new drug application to the FDA for review. In exchange, the agency has to meet review deadlines to help speed up the application process. This all means the regulator has far fewer funds to put toward making sure drugs already on the market are safe. It also means the industry gets a lot of deference.

“User fees provide access to FDA decision-makers in ways that foster a cozier relationship between FDA and industry,” said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, a think tank that focuses on the safety of medical and consumer products.

The agency has taken heat in the last year and a half for approving an Alzheimer's disease drug that wasn't fully proven to work, leading to accusations that the body is too beholden to the drug industry. The FDA also let clear signs of problems at an Abbott Laboratories' infant formula plant slip by for almost five months before overseeing a recall and temporary closure of the factory in February, which ultimately led to a national formula crisis. These fiascoes have consumed the agency at a time when it’s been overwhelmed by the race to approve Covid-19 treatments and vaccines. All the while, recalls of sunscreen, antiperspirants, hand sanitizers and dry shampoo keep piling up.

When the FDA required Zantac be pulled from the market, it was a rare move. Typically, the agency allows companies to fix problems on their own.

“Manufacturers are the most familiar with their own processes, facilities and supply chains, and are therefore best positioned to quickly assess a safety risk,” the FDA’s Harrison said.

GSK “routinely tests its products to ensure safety and consistency throughout their lifecycles,” Lyndsay Meyer, a spokeswoman for GSK, said in an emailed statement. “However, prior to 2019, registered testing specifications for Zantac did not require testing for NDMA.” NDMA, or N-Nitrosodimethylamine, is the contaminant found in Zantac.

Zantac Recalls

Valisure alerted the FDA to troublesome findings on Zantac and its generic versions early in the summer of 2019, Light said. The lab then officially filed a petition with the agency that September, making the information public and asking for recalls and for drugmakers to suspend sales of the drug. It appeared from Valisure’s testing that the active ingredient in Zantac can form the probable carcinogen NDMA. Novartis AG's Sandoz unit recalled its generic version of Zantac several days later. Sanofi recalled all over-the-counter Zantac a little more than a month later and the recalls continued to roll in through February, including generic versions made for CVS, Walmart, Rite Aid and Target private-label brands.

Rather than embrace Valisure as a partner in protecting the public, the FDA instead turned combative.

On May 24, 2021, Valisure released its findings showing cancer-causing chemicals in sunscreens. Two days later, two FDA inspectors showed up at the lab, according to agency documents. They brought an FDA lawyer with them for three of the 11 days they were at Valisure. The three FDA employees were deployed to the Valisure lab at a time when the regulator was focused on conducting its most critical inspections amid a pandemic backlog.

Valisure has about 20 employees who work in an office space of about 6,000 square feet in New Haven, Connecticut. The FDA, to compare, operates in 3.1 million square feet of office and lab space on a sprawling campus in Silver Spring, Maryland. It has 18,000 employees and a $6 billion annual budget.

FDA Inspection

When the FDA inspectors came knocking, they demanded access to Valisure’s records and lab space, the inspection documents show. They showed up claiming they had proof Valisure was running tests to help pharmaceutical companies gain US approval for their drugs, which the lab maintains it has never done.

Light remembers the lead inspector repeatedly saying he didn’t really understand why they were there and that he wasn’t able to produce the proof the FDA said they had.

The FDA said as a matter of policy that the agency “does not comment on regulatory evaluations including inspections until there has been a final determination,” adding that it has “confidence in the training and qualifications of our investigators to conduct the inspectional work they are assigned.”

“The FDA’s inspectional activities are a core part of the agency’s safety work,” Harrison said.

Eventually, the inspectors wrote up a report listing violations they say Valisure committed by not operating with all the controls a drug manufacturer would, something not necessarily needed by a small testing lab that isn’t making drugs. The agency has left the inspection hanging open for more than a year.

In the meantime, the pharmaceutical giants that Valisure has been policing are going after the lab as well.

Consumers have sued drugmakers like GSK and Sanofi over the Zantac contamination. In response, the pharmaceutical companies are attempting to prove a conspiracy theory. As part of their defense, they claim that Valisure schemed with plaintiffs’ lawyers using faulty testing methods to profit off the companies that sold the medications.

The FDA said Valisure's original testing method inflated the amount of NDMA found in Zantac because its experiment used heat. Since the lab was on the frontlines of this problem, there was also no universally agreed-upon test, and the FDA has since worked to come up with one. The method the agency developed also found elevated NDMA levels in Zantac, though the levels weren't as high as what Valisure found.

“While attempting to replicate Valisure’s test results, FDA testing revealed an overall disparity between our testing results and Valisure’s testing results on the same product lots,” Harrison said.

Legal Entanglements

Plaintiff's lawyers have also gone after Valisure for meeting with members of Congress to discuss the need for independent testing, saying they've tried to exert undue influence on the scientific process. In some cases, concerned members of Congress came to Valisure to ask for briefings. In others, Valisure has pushed for legislation to require independent testing of products — a mandate that would likely boost the lab’s revenues, but also a normal tactic for a business.

Valisure has so far spent about $500,000 in legal fees producing more than 1,600 documents and emails related to the Zantac case. A judge rejected another subpoena request from drugmakers for more documents in an attempt to further their conspiracy theory defense against Valisure. The plaintiff’s lawyers in the Zantac case have said they don’t even plan to use Valisure’s testing in trial. (Valisure itself hasn’t been sued.)

It’s high-stakes litigation. Damages from the Zantac lawsuits could possibly reach $10.5 billion to $45 billion, analysts at Morgan Stanley said in August.

For its part, GSK said it will "vigorously defend" itself against any claims Zantac increases cancer risk, said Meyer, the company spokeswoman. Sanofi said it is “fully confident in its defenses to the litigation.”“Sanofi began marketing Zantac in 2017 based on the medicine’s more than 30-year track record of providing patients safe and effective heartburn relief,” the company said in an emailed statement.

The FDA did its own testing of Zantac and its generics in 2019, following Valisure, and found tablets with as much as 860 nanograms of NDMA, nine times the amount the agency has determined is allowed in drugs. The agency later said it also determined NDMA levels in Zantac and generic forms can grow over time and in higher room temperatures.

Sanofi brought Zantac back to the market in April 2021, replacing the active ingredient ranitidine with famotidine, the same active ingredient in another heartburn medication, Pepcid.

Connecticut Offices

Valisure’s New Haven offices are less than a mile from Light’s alma mater of Yale University, where he studied molecular biology. Light, who often dresses in trim, tailored suits, comes across as equal parts businessman and scientist. Valisure started in 2015, when co-founder Adam Clark-Joseph convinced Light there was a gap in the pharmaceutical industry they could fill by testing drugs beyond what the FDA handled. The idea was sparked after Clark-Joseph had suffered severe complications from a bad batch of medicine. Then in 2018, they began operating as a pharmacy that tested its drugs for impurities before dispensing them to customers.

Pretty soon, Valisure found itself rejecting 10% of the drugs it purchased because of contamination or other concerns, such as a lack of active ingredient.

As its testing business took off and it found more and more products contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals, the company sold its pharmacy last year to focus on the analytical lab experiments.

The company’s goal is to eventually make money picking up where the FDA leaves off, offering makers of consumer goods reliable, independent contaminant testing. Already, a large drug purchaser that Light says has asked to remain anonymous has partnered with Valisure to check the quality of certain products. Gojo Industries, which makes Purell hand sanitizer, has also partnered with the lab.

Valisure’s largest investor is Realist Ventures, also based in Connecticut, and the company has raised funds from individuals, mainly doctors and lawyers, Light said. The company is planning a series A funding round soon but declined to disclose the amount of funding it’s seeking.

While Light was pointed toward analyzing Zantac because NDMA was already top of mind in the pharmaceutical industry given the recalls for blood pressure pills the year before, he directed Valisure toward testing sunscreens and deodorants on more of a “hunch” by his chief scientific officer.

So far, no other independent labs have followed Valisure’s testing on the personal-care products. But the best evidence to support the lab’s findings comes from the product recalls. Both Unilever and P&G, for example, cited benzene contamination in recent recalls for dry shampoo.

Aerosol Sprays

The common thread between many of the carcinogen-laced cosmetic and grooming products is that they’re delivered through aerosol sprays that use propellants made from petroleum products, such as propane and butane. Many experts think it’s the propellants used in the aerosols, rather than the products themselves, that are the problem. It’s a peculiar twist because the industry only started turning to petroleum-propellants after an older technology was found to be hurting the ozone layer.

Valisure has so far only tested a tiny percentage of the cosmetic and grooming products that could end up being linked to carcinogens. There’s no telling how deep the problem goes — the market for personal-care products made with aerosols is worth about $3 billion.

Despite his battles with the FDA and giant corporations, Light seems determined to keep digging.

“I always love doing exciting, impactful things that make a difference in some way,” Light said. “It’s been very impactful science. You can argue my methodologies all day, but they’re still right.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.