Aug 28, 2020

Abenomics Era Ends With Japan’s Economy Back at Square One

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The almost 8-year era of Abenomics draws to a close with Japan’s economy right back at square one.

Prices are flat lining and the deflationary mindset seems as entrenched as ever. Many of the women who entered the labor market under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s tenure are losing jobs as Covid-19 batters the economy. Households and companies are in saving mode again amid the pandemic, forcing the government to borrow heavily to cushion demand.

It wasn’t meant to end this way. Abe, who announced on Friday afternoon in Tokyo he would step down due to health problems once his ruling party decides on a successor, came to office with grand plans to snap Japan out of its two decades of stagnation. What would become known as Abenomics relied on “three arrows”: monetary easing, fiscal policy and regulatory reforms.

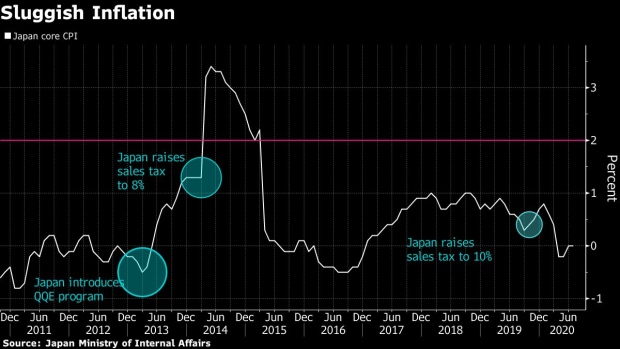

There were quick successes. Newly-appointed Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, hand-picked by Abe, pleased markets with ultra-low interest rates and bond-buying that drove a rally in stocks and sent the yen lower, boosting exporters. Inflation even started to perk up and officials were able to declare Japan had clawed its way out of the deflation that had plagued its economy for so many years.

Japan’s Longest-Serving Premier Abe Resigns Due to Health

As companies reported record earnings, Abe repeatedly urged them to raise wages so that workers would be more willing to spend. While pay did rise, it was never quickly enough to spur the sustained pick up in spending that was needed to drive inflation securely to the BOJ’s 2% target.

Also at Abe’s urging, the female labor participation rate steadily climbed, reaching a record high. That’s helped the economy continue to expand, albeit at a modest pace, despite Japan’s aging workforce. Tourism boomed, helped by a weaker yen and regulatory changes. The Tokyo Olympics, which were to have been this summer, fueled investment and were meant to be a highpoint for the nation’s economy.

Kathy Matsui, vice chair of Goldman Sachs Japan, who has long advocated a shakeup of Japanese society to better harness women in the workforce, said Abenomics will be remembered for, on balance, growing the economy, creating jobs and keeping deflation at bay. “The question going forward is will the next successor be able to tackle the remaining reform agenda items, and will the successor be able to bring Japan once and for all out of deflation,” she said.

The clear wins of Abenomics end there.

Even before this year’s massive rescue package worth about 40% of GDP, the budget remained deeply in the red, despite the fact that Abe raised the sales tax in 2014 and 2019. Regulatory reforms to cut red tape failed to really overhaul the system or initiate enough innovation to notably boost productivity. One example: aged administrative systems delayed the distribution of payments to households in recent months, weighing on recovery prospects.

The impact of monetary easing also weakened as the years rolled on, with a turning point being the BOJ’s introduction of a negative interest rate in 2016. That led to concerns that the policy was weighing on the profitability of financial institutions -- particularly small rural lenders.

Abe’s second sales tax hike in October 2019 turned out to be spectacularly ill-timed. First, major typhoons hit the economy. Then, the coronavirus put everything into tailspin. The BOJ has had to shift its focus from trying to revive inflation to throwing lifelines to businesses with new lending programs and yet more asset purchases.

The upshot: domestic demand continues to rely heavily on government spending and the prospect of a robust expansion that can generate a sustained acceleration in inflation appears distant -- just like it did before the start of Abenomics. And after the Covid-induced second quarter slump, the economy has shrunk back to its size after the 2011 tsunami and nuclear disaster.

What Bloomberg’s Economist Says

“In the short term, we don’t anticipate any significant changes in macro policy. The Bank of Japan, under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, is set on supporting Japan Inc. during the pandemic and has a flexible policy framework in place under which it can scale stimulus as needed. Fiscal policy is basically set for now with massive stimulus packages in place.”

-- Yuki Masujima, economist

Click here to read more.

“Every time the global economy takes a turn for the worst, Japan gets dragged down by it,” HSBC Holdings Plc global chief economist Janet Henry told Bloomberg Television. “As much as I think the history books will treat him well in terms of trying to deliver some transformational changes, it shows what happens in an economy that can still be quite export dependent and still has a number of domestic challenges.”

It’s unclear what comes after Abenomics. But economists don’t see any imminent change in the direction of monetary policy, since Kuroda’s term doesn’t end till April 2023. The bank will continue with its current monetary easing despite Abe’s resignation, people familiar with the matter said. Still, stocks fell earlier Friday as news of Abe’s resignation began to emerge.

In his press conference Friday, Abe acknowledged that the pandemic has had a “major economic impact,” but said his government has managed to contain the damage relatively well compared with other developed nations. As to his legacy, “it’ll be decided by the people and by history,” Abe said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.