Aug 22, 2019

After Auction Fiasco, Nazi Type 64 “Porsche” Fades Into Shadows

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The failed sale rang like a gong throughout the car world on the night of Aug. 17 in Monterey, Calif.

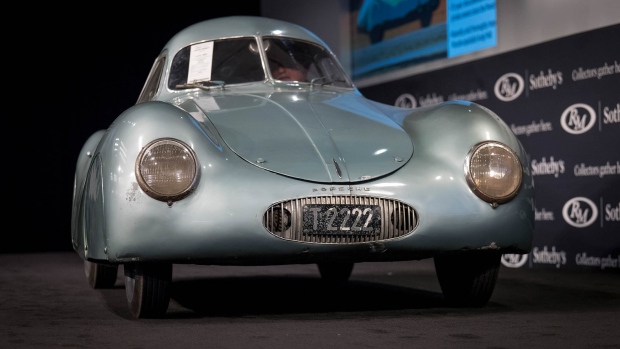

A spectacular auction blunder left the 1939 Type 64, the first automobile to bear the Porsche name, without a buyer. Now, as members of the classic car community try to figure out exactly what happened, the historic coupe is slipping back into the murky shopper’s purgatory where it lingered in recent years.

This was the biggest snafu in recent auction history, caused by confusion at the auctioneer’s podium during the sale of what RM Sotheby’s had billed as a $20 million Porsche. The catastrophe may have been matched only by a 1990 Christie’s fiasco involving a mistaken identity on an Alfa Romeo. But that one didn’t involve Nazi intrigue.

Since Saturday, new discrepancies have emerged, including the fact that while the auction catalogue noted that the Type 64 came with a “Bill of Sale Only,” RM Sotheby’s now says its German owners—since revealed as the billionaire Schoerghuber family active in the beverage, hotels, and aircraft industries—hold a “European title” of ownership, rather than a bill of sale statement declaring proof of a transaction.

In the grand scheme of things, the switch doesn’t affect much. Very old cars, especially race cars, often lack titles. But you didn’t have to be there on Saturday night in Monterey to sense the impact of the scandal; the volume of YouTube views and Instagram comments on the incident quickly reached into the hundreds of thousands. Collectors, enthusiasts, and onlookers alike were shaken.

The Background

After founding his eponymous consulting firm in 1931, Ferdinand Porsche worked as a hired gun for European automakers, including Volkswagen and Mercedes-Daimler, long before he made the Type 64 coupe, which was initially black. He developed the coupe on commission from the National Socialist Motor Corps for Nazi propaganda purposes. That was nearly 10 years before the Porsche brand he later founded produced its first car, the 1948 Porsche 365 Gmuend Coupe.

Though it certainly represents an important bit of history, the Type 64’s failure to sell did not surprise close observers.

The car is known to have been shopped for years at various prices well under the $20 million value RM Sotheby’s assigned it. Several prolific collectors were approached about buying it in the months, weeks, and days leading up to the auction; each declined.

Asked why they passed, they offer different responses to Bloomberg—personally or via brokers—none of which have to do with the car’s Nazi history. Indeed, practically all German-made cars of that era were completed under Nazi duress, with Volkswagen’s Beetle the most famous and best-loved. Instead, they say, the aversion to the Type 64 has to do with the fact that the car is over-exposed: It has been offered for sale for years, an open secret among the few collectors wealthy and interested enough to afford it. This is a tiny, elite group to begin with; they all know each other. At this point, they say, it would be ridiculous to buy the Type 64 at a public auction for millions more than they could have bought it years ago. It doesn’t help matters that Porsche itself has chosen not to give the car any official seal of approval.

The Type 64 also lacks the performance chops of many of its Mercedes contemporaries. With a maximum strength of just 40 horsepower, it is not an exceptionally thrilling car to drive, physically speaking, though it does still run. “It has got a sewing-machine-sized engine at a fire-breathing Le Mans price,” one source puts it.

So What Happened?

RM Sotheby’s scheduling of the lot during the auction evening hinted at the house’s lack of confidence about its allure, according to someone familiar with the company’s practices. Placed at 362 out of 376 lots, which put it late at night on the final day of sales, the Type 64 was virtually buried for what was supposed to be the weekend’s glittering moment. It was positioned in the roster to inflict the least amount of gloom on the crowd if it didn’t sell; auctioneers would soldier on through the rest of the lots.

The surprise lay in just how it all went down. What happened remains disputed.

Here are the facts: RM Sotheby’s auctioneer Maarten ten Holder started the bidding on the car at either $13 million or $30 million, the latter being the sum posted on the screen at the front of the room. RM Sotheby’s has said in statements to Bloomberg that ten Holder stated $13 million, but that his accent was misunderstood by the person running the numbers on the screen, who—perhaps overeagerly—reflected the $30 million figure. (At no other point during the two-day sale did ten Holder appear to have been misheard, however.)

Bidding rapidly climbed from there. While ten Holder declared increments of $500,000, the numbers on the screen went up by $10 million. You can see the rapid series of events in Instagram videos from audience members.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by David Lee-Ferrari Ambassador (@ferraricollector_davidlee) on Aug 18, 2019 at 12:35am PDT

It went from $40 million to $50 million to $60 million in moments, according to the video screen. It was difficult to discern whether ten Holder was saying “fourteen,” “fifteen,” and “sixteen,” but regardless, the general consensus among dozens of people who were in the room and interviewed for this story is that those bids illustrate the practice of “chandelier bidding,” wherein an auctioneer uses phantom bids to raise excitement. The hope is that the imaginary numbers will drive up the dollar amount of bids up to near an item’s reserve value, at which point it’s hoped that an actual human will offer a legitimate bid. (In whipping the crowd into a frosted-icing frenzy, the auctioneer points to faux bids as if he’s pointing to the chandeliers above, hence the elegant name for a shady practice—which is legal, so long as the auction house notifies both buyers and sellers contemporaneously and the ghost bids don’t result in a sale.)

“An auction house can, on behalf of the consignor, effectively bid the car up to its reserve,” says Damen Bennion, a London-based contract lawyer specializing in the collector car market who was present during the auction. “That is what we saw happen. That is not unusual. There is nothing wrong with that.”

Still, it’s unusual in a car auction for the increments to be so large. A $10 million jump is huge at Pebble Beach, where this year’s most expensive car was a 1994 McLaren F1 “LM-spec” Coupe that RM Sotheby’s sold for $19,805,000.

Disaster Strikes

Bennion says he believes that a flub happened when the person controlling the numbers board misheard ten Holder. The amounts of money—and the excitement in the room—expanded like a mushroom cloud. Things then went from bad to worse.

When the figures on screen reached $70 million, ten Holder suddenly stalled the wild bidding, laughing and shouting to the phone bank along the side of the room that the media wall should reflect $17 million, not $70 million.

It’s an understatement to note that the numeric adjustment displeased the crowed. People started booing and yelling “fraud,” “fake,” and “scam.” Others walked out. Bloomberg News covered the blow-by-blow.

If the discrepancy were an honest misunderstanding regarding the thick accent of a native Dutchman (ten Holder is a polyglot), observers wonder why it wasn’t addressed faster.

“I don’t know why [RM Sotheby’s head] Rob Myers didn’t immediately jump up and correct things,” Bennion says. “For a brief period of time, we all thought we were privy to something special.”

“As soon as the bid display screen error was noticed amongst the excitement in the room, the auctioneer clarified the spoken bid, and the display screen was corrected,” a spokesperson for RM Sotheby’s countered in a written statement to Bloomberg.

I spoke with at least 15 people close to the situation, including former employees of RM Sotheby’s, collectors, lawyers, historians, builders, auto brokers, and even a spokesman for Porsche AG. Some point to the fact that at no point during the rest of the sale was there such confusion about ten Holder’s diction, even when dealing with such other high-impact cars as the $19 million record-breaking McLaren F1. They say that, since it was known among insiders that there was no bid to be had, ten Holder either attempted a sort of tongue-in-cheek comic relief that went wrong or deliberately under-pronounced words in order to somehow jump-start live bidding. The spokesperson for RM Sotheby’s vehemently denied the claims.

“My view is there was not one bid at that auction—not one,” Bennion says. “The car has been for sale for a number of years. It has been offered to all the big collectors and to Porsche, and they have rejected it. It was always going to be a difficult sale. RM Sotheby’s pushed the car very hard. There was a lot of media done to raise its profile. If Porsche itself didn’t want it, and that was known in the market, then the likelihood of RM selling it was very slim.”

Why Did It Happen?

Regardless of intent, the shocking turn of events leaves many questions as to how such a snafu could happen, the destiny of the unquestionably historically important car now carrying a black eye, and current and future practices at RM Sotheby’s and other blue-chip auction houses.

Perhaps the overarching motivator on the part of RM Sotheby’s to make the Type 64 into a phenomenal sale was the cutthroat nature of the high-end car auction world. Auction houses such as RM Sotheby’s, Gooding & Co., and Bonhams compete to win the most prized, prestigious, and priciest car consignments from around the world, and the sellers want as much money as they can get from a sale. It’s natural that prospective sellers will go with whichever auction house posted the highest recent sale of a comparable vehicle and can promise them the highest bids.

There’s where the funny business starts.

“I think that has led to some of the competitiveness that RM has exhibited in getting vehicles in their pipeline,” says Paul Zuckerman, a lawyer in Beverly Hills, Calif., and co-host of a well-known podcast about all things cars. “They make crazy deals. They make guarantees. They pay money against auction proceeds upfront. They want to make the numbers work and satisfy whatever targets their corporate masters have over them.” (Founded in 1991, RM Auctions formed a partnership with Sotheby’s in 2015 to become RM Sotheby’s, with Sotheby’s acquiring a 25% ownership stake in the new entity.)

Motivation to win big cars and high sale prices is also what prompts the impulse to save face should such a highly promoted car as the Type 64 fail to garner interest. More than a few observers have suggested that the bidding process on Saturday in Monterey marked an attempt to maintain the perception of prestige and control over what is ultimately a used-car sale, like every classic car auction. Then, as when the curtain was pulled back in The Wizard of Oz, the game was revealed.

“It’s a perfect storm right now,” Zuckerman says. “There are too many auction houses auctioning too many cars. And then you get too many questionable cars. The auction houses—if they’re going to survive in the long run—they really have to double down on curation and careful vetting of what they’re selling. Reputation is everything.”

That environment has already spawned the success of such online auction platforms as Bring a Trailer, which recently introduced a new premium category of cars for sale in order to appeal to better-heeled buyers. Randy Nonnenberg, the founder of BAT, did not respond to requests for comment.

As for the Type 64, it will be “jolly difficult, if not impossible” for the Schoerghubers to win a lawsuit against RM Sotheby’s complaining about the botched sale, Bennion says. “The terms and conditions are very clear.”

It doesn’t help that the industry has little regulation, unlike venues for other commodities that are traded. Auction houses use the proviso “terms and conditions apply” to its fullest extent, allowing them to act as middlemen rather than assuming any culpability for the quality and authenticity of their wares. Witness the drama surrounding the 1958 Porsche 356 Speedster that Jerry Seinfeld commissioned to Gooding & Co. in 2016.

The buyer, FICA FRIO Ltd., claimed that the car’s authenticity was misrepresented and sued Seinfeld to request that the sale be rescinded, with a refund and additional punitive damages. Seinfeld ultimately filed a countersuit against European Collectibles, the company that had restored the car for him before he consigned it. Gooding & Co., meanwhile, emerged scot-free. The moral of the story when buying anything at auction? Caveat emptor.

What’s Next?

When there is no buyer for a particular car at a major auction, the terms and conditions apply again, in this case stipulating that RM Sotheby’s reserves the right to try to sell the Type 64 for 60 business days following the auction. The idea is that the $17 million reserve can be adjusted down to a more realistic number and a deal done with a new buyer, privately.

The car is likely to remain in California for that time period, since the United States presents a plumper buyer’s market. If it finds no quarter with a new buyer, it’ll return to the Schoerghubers, likely to re-emerge in a few years with a new owner after the scandal blows over—if the scandal blows over. (“The car is f---ed,” opines Zuckerman.)

As for RM Sotheby’s, the partnership’s fate remains unclear. Some insiders say Sotheby’s proper is “furious” with the way the sale was handled and particularly with Myers, who has a polarizing reputation. Could the firm take a hard look at continuing the partnership? “There is no change to the RM and Sotheby’s partnership,” a spokesperson for RM Sotheby’s said in a written statement to Bloomberg. Sotheby’s did not respond to requests for comment.

Others say it’ll all be back to business as usual in no time.“These things are generational,” says Zuckerman. “The scandals are never new. The new scandals are the same scandals—just a different year.”

To contact the author of this story: Hannah Elliott in New York at helliott8@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.