Oct 6, 2021

Al Gore’s $36 Billion Fund Sees New Urgency to Cut Off Oil Money

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Five years. That’s roughly how much time the investment universe has left to stop feeding capital to greenhouse-gas emitters before it’s too late, according to the co-founder of Generation Investment Management LLP.

David Blood, a long-time top executive at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s asset-management unit before starting an investment fund with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore more than 15 years ago, says that efforts over the past two decades to fight climate change are “not going to be enough.”

“The urgency of the challenge will require us to think differently around capital allocation,” Blood said in an interview. “And we don’t have 15 years or 18 years to get there. We have probably five years.”

With that timeline in mind, the idea of providing capital to a whole range of so-called transition assets -- fossil-fuel businesses that pollute a lot now but say they won’t in the future -- is hard to defend, according to Blood. And not just from a climate perspective, but from a financial standpoint. They’re “poor investments,” he said. So Generation Investment Management has blacklisted hydrocarbon securities for more than a decade.

For investors committed to fighting climate change, quitting fossil fuels may seem like an obvious thing to do. But many -- in fact, most -- in the industry argue that it’s better for investors not to pull their capital and instead help carbon emitters reform themselves. Time will tell which strategy is wisest. But for now, there’s a growing body of research to suggest that the financial industry as a whole is failing in the fight against global warming.

A recent study by EDHEC Business School concludes that “de facto, the investment industry, in spite of its promises, does little to reallocate capital in a direction and in a manner that could incentivize companies to contribute to the climate transition.” At the same time, a recent United Nations study found that without more ambitious national plans, emissions will continue to rise.

Unless wealthy nations commit to tackling emissions now, the world is on a “catastrophic pathway” to 2.7 degrees Celsius of heating by the end of the century, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently warned.

Some of the biggest polluters on the planet are the largest oil producers, most of which have enjoyed double-digit share-price increases this year. Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp., Royal Dutch Shell Plc, BP Plc and TotalEnergies SE together emitted 8.5% of the world’s total carbon dioxide in 2020, with Exxon Mobil standing out as the worst among them, according to estimates from Bloomberg Intelligence. The majority of U.S. oil majors so far haven’t set net-zero targets that encompass so-called Scope 3 emissions, which include those of end users.

For years now, the price of fossil-fuel securities hasn’t reflected the “stranded asset risk,” Blood said. “And so we have made a very clear investment decision based on the urgency of the transition.”

When Generation Investment Management was founded, Gore was doing the rounds delivering speeches on global warming. After the former vice president’s 2006 documentary, “An Inconvenient Truth,” became a box-office hit, the issue of climate change was forced onto the awareness of the general public.A year later, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its fourth assessment, which alarmed those who read it but didn’t really move governments to embrace meaningful change. In its latest report, the IPCC makes clear human activity is driving temperatures up much faster than previously feared, and the only way to save the planet is to dramatically cut CO2 emissions.

Generation Investment, which now has about $36 billion of assets under management, will be among the participants at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties in Glasgow, Scotland, in November, widely seen as a make-or-break moment for humanity to avert an irreversible climate catastrophe. Blood says he hopes those attending will agree to a “higher price for carbon.”

Another concern is whether governments do their bit amid growing evidence that pledges aren’t being met. The UN is urging all nations to submit more ambitious emissions plans by the time COP26 gets under way, if the planet is to avoid temperature increases above 1.5 degrees Celsius.

There needs to be “better government signals and regulation” to steer capital away from old energy, said Blood, who wants to see a “series of guardrails” imposed over the next three to five years.

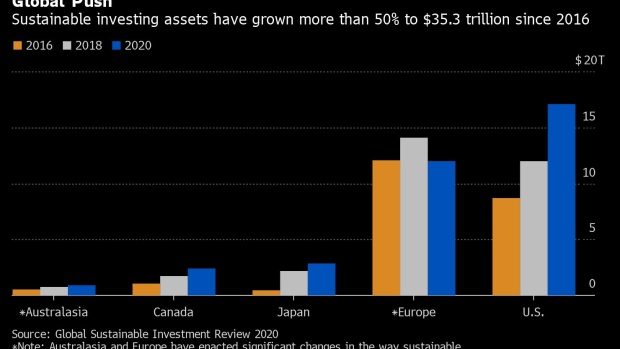

As Blood tries to convey the sense of urgency he feels around the need to fight climate change, he acknowledges there’s also a growing sense of skepticism toward the notion that the financial industry can help. The increasingly lucrative market for environmental, social and governance investing -- estimated to exceed $50 trillion by 2025 -- has drawn criticism and even scorn from some ex-industry insiders. Most notable among them is Tariq Fancy, a former sustainability head at BlackRock Inc., who’s since published a series of exposés that he says prove how shallow many ESG promises are, and how pointless much of the industry is.

And there’s more and more evidence he might be right. In Europe, where ESG regulations are much further advanced than in other jurisdictions, the financial industry has been forced to strip the label off $2 trillion of assets, suggesting much of that amount had been greenwashed. The expectation is that a similar reckoning faces investment managers in the U.S. and Asia once their regulations catch up with those in Europe.

Blood, who declined to comment on Fancy, says some skepticism is understandable. But he says he’s worried that too much cynicism might ultimately hamper genuine efforts to steer capital away from polluters.

“To simply say that sustainability and ESG is not relevant, I think that would be unfair,” he said. “We know that what we’ve been doing over the last 50 years is unsustainable. What we need to do is use whatever tools we can to fundamentally change capital allocation.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.