Feb 17, 2022

Americans are paying more for worse stuff, study finds

, Bloomberg News

The cost of everything is going up fast, and we're in it for the long haul: Derek Holt

Measured by consumer prices, U.S. inflation is the highest in 40 years. Look at what Americans are actually getting for their money and the rate may be even higher, according to researchers at the University of Michigan.

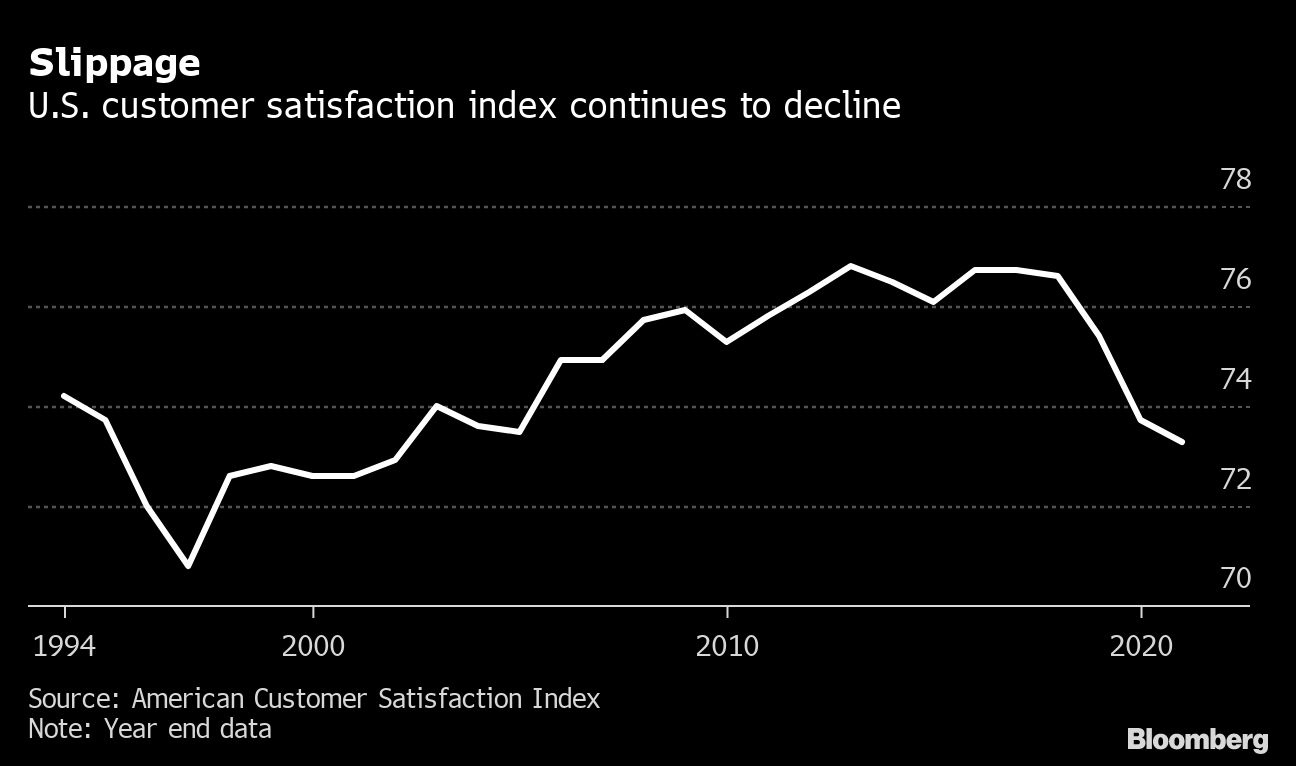

The academics publish a quarterly American Customer Satisfaction Index, which seeks to measure how happy consumers are with the goods and services they spend on. The latest edition, released earlier this week, found that there’s been a 5.2 per cent decline in quality since 2018, with the bulk of it coming in the pandemic years.

The question of quality is an important and difficult one for statisticians trying to measure inflation. They have to account for cases where the price of a product -- a laptop computer, say -- hasn’t changed very much but its quality has improved, because technology allows faster processors and better screens. That means that in a sense, the computer is cheaper. And conversely, if the price is unchanged and the product has gotten worse, that effectively means it’s become more expensive.

The experts at the Bureau of Labor Statistics who calculate the headline U.S. inflation gauge, the consumer price index, try to incorporate a quality adjustment -- known in the jargon as “hedonic changes.” But they do it for fewer than 40 of the 273 items whose prices they monitor, or about 13 per cent of the CPI basket.

The Michigan researchers attempt to measure quality across all the industries they track. Their latest findings “suggest that actual annualized inflation is probably about 10 per cent” if prices were “fully adjusted for quality decline,” the report says. The January CPI showed consumer prices rose 7.5 per cent from a year ago.

The dropoff in satisfaction is “most pronounced in services,” says Claes Fornell, founder of the ACSI and a professor emeritus of business administration at the University of Michigan. “Due to the pandemic, the problem has been amplified by a lack of product availability, supply issues and labor shortages.”

The ACSI report highlights a few examples of COVID effects. It found that some of the worst declines in quality came in consumer electronics, hit by supply-chain issues; at hotels, where a lack of workers means nightly room-cleaning is no longer available in some cases; and in video streaming, where system overloads occurred because more people were stuck at home trying to watch the same shows all at once.

One caveat to the ACSI: The index is based on surveys, making it a sentiment gauge of perceived quality. The respondents’ opinions are more loosely defined than the specific characteristics associated with each item that the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks for prices.

How people feel about a product or service may be reflected by their own personal experience with dealing with a company than in how quality has changed.