Jan 25, 2023

Architect of Brazil’s Inflation Target Says It’s Time to Ease It

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has rattled financial markets by criticizing the central bank and Brazil’s inflation target for being too restrictive. The main architect of the system that keeps consumer-price growth in check agrees — it’s long past time to relax the goal.

Sergio Werlang, an economist who designed the inflation-targeting regime more than two decades ago, says the goals of 3.25% for 2023 and 3% for next year are far too low. In trying and failing to reach such levels, he adds, the central bank is sacrificing growth and as well as its own credibility.

Policymakers “put themselves in a corner and they don’t know how to get out of it,” Werlang, a former director of economic policy at the central bank, said in an interview on Tuesday.

While Werlang represents a minority view in Brazil’s financial circles, many in government would agree with him. Since Lula took office on Jan. 1, a debate has been reignited over whether the central bank’s inflation policies are too stringent for a developing nation with outsized debts and large susceptibility to swings in commodity prices.

The fracas over Brazil’s inflation goals follows a growing discussion among prominent economists and investors about the 2% target adopted by the Federal Reserve and other central banks in developed nations, which critics say cause economies to run too cold.

Read More: Lula’s Jab at Central Bank Puts Traders on Edge Across Brazil

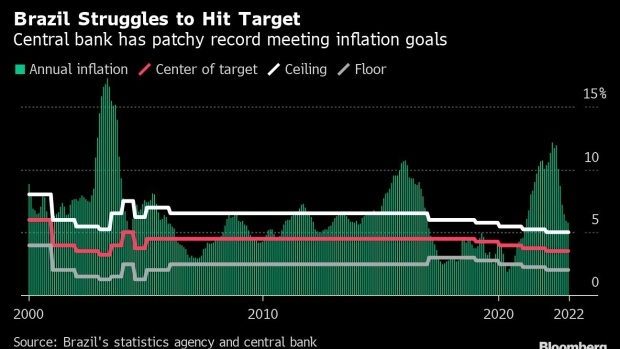

Lula, 77, is beefing up the state’s role in the economy in his quest to spur growth and fight poverty. Investors have balked at the plans. They come as annual inflation is running well above target at 5.79% and after the central bank, under the leadership of Roberto Campos Neto, blew past its goal for two consecutive years as it copes with the effects of Covid-19.

“We are proving it right now that minor or major shocks, like the pandemic, may upset the system so much that in order to go back to 3% it’s gonna be extremely painful in terms of GDP,” he said.

Hyperinflation Past

Werlang, 63, knows better than most how the system works. In 1999, then central bank chief Arminio Fraga invited Werlang, a former classmate from Princeton University, to join the bank to develop and implement inflation targeting in Brazil.

Latin America’s largest economy suffered various bouts of hyperinflation in recent memory. Under the system Werlang created, a government body known as the National Monetary Council sets an annual consumer-price increase goal with a certain leeway — currently of plus or minus 1.5 percentage points. If the central bank fails to hit it, it must explain to congress in writing what went wrong.

The council, comprised of the central bank president plus the ministers of finance and planning, is slated to meet in June to discuss 2026 inflation goals, and could change or reaffirm previous years’ targets.

Werlang, now a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, has criticized the government’s decision to lower its inflation goal from 4.5%, which he believes is the ideal target. After holding steady at that level for more than a decade, the government began reducing the target by a quarter percentage point a year, starting in 2019.

Werlang argues that, unlike Chile and Mexico who target 3% price growth this year, Brazil faces far too many spending commitments that are difficult to adjust quickly — something he calls “fiscal rigidity.” The only way to get around these outlays, barring constitutional changes, is through inflation slowly eroding entitlements and wages.

Indeed, payrolls, social security and other mandatory spending account for about 79% of the federal government’s total expenditures, according to Brazil’s Treasury.

In the wake of coronavirus and the reopening of the economy, the central bank embarked on a monetary tightening campaign that took the benchmark interest rate to a six-year high of 13.75%. It has pledged to hold it firm as concerns over Lula’s spending plans push up inflation expectations.

Analysts, though, expect the bank to keep missing its goals through 2025, even as economic growth is forecast to slow to less than 1% this year.

With such little fiscal space to work with, “it’s going to cost society a lot to lower inflation to around 3%,” he said. “Why not just accept that we need a higher target?”

Campos Neto has so far rejected the notion of adjusting price-growth goals, saying it would do little to boost the bank’s credibility.

Werlang said that if the target isn’t changed carefully, the transition could end up damaging the bank’s reputation. But, he added, so does repeatably missing the mark.

--With assistance from Maria Eloisa Capurro, Mariana Durao and Shawn Donnan.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.