Jun 1, 2023

As Asia Strives to Spur Births, Philippines Wants Fewer Babies

, Bloomberg News

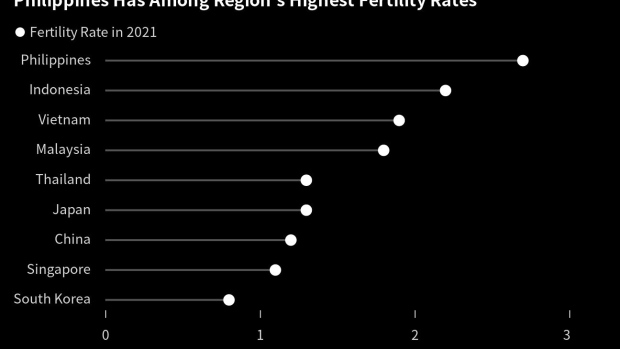

(Bloomberg) -- As birth rates plummet across Asia and beyond, the Philippines stands out for having among the highest fertility ratios in the region.

For years, the Southeast Asian nation has wrestled with a dilemma considered enviable in countries like Japan and South Korea, where governments are offering cash incentives for couples who have children. As many countries record more deaths than births, the Philippines is a bright star for those who believe a young labor force portends greater productivity.

But officials in the Philippines, which has 113 million people, see the issue differently. The government, led by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., warns that the country can’t achieve broad economic success without addressing demographic challenges.

The Philippines, despite sterling growth rates for most of the past decade, still ranks among the poorest in the neighborhood and lowering the birth rate — which is more than twice South Korea’s — is a key strategy for development metrics. Changing attitudes around family planning has proved a tall order in the Catholic-majority country. Elevated fertility rates are intertwined with religious and cultural expectations, and also underscore weak access to contraceptives and health care services.

One-third of the output gap between the Philippines and its well-off Asian peers can be “attributed easily to the fact that we haven’t entered the demographic dividend,” said Arsenio Balisacan, secretary of the National Economic and Development Authority.

Though a smaller labor force might be a problem in wealthy nations, Balisacan said officials in those places have the money to invest in technology and development. In the Philippines, more people are putting great strain on limited resources. The government has made family planning one of its biggest budget priorities this year.

“The most basic, most fundamental problem is to get our poor out of their situation and improve access to services so that everybody’s lifted up,” he said.

The verdict is mixed on what a declining population means for the world. Fertility rates are easing as incomes rise and access to contraceptives improves, on top of changing attitudes among women about having children later in life, or not at all. The United Nations now expects the number of people to peak at 10.4 billion by 2100, a decline from earlier estimates exceeding 11 billion.

Even if shrinking population is good for things like environmental sustainability, graying demographics present challenges, including rising health care and retirement costs. Nowhere is that thesis more testable than in Asia, where fertility rate declines are among the most extreme.

In Japan, where birth rates have dropped for years, the government announced fresh measures to boost the numbers, paving the way for doubling the budget spent on children. In China, the population shrank last year for the first time since the 1960s, and officials are campaigning to change decades-old attitudes about the size of families.

The numbers are even starker in South Korea, which holds the unfavorable crown of having the world’s lowest fertility rate, at 0.78 children per woman. Officials are turning to robots and drones to fill gaps in military recruitment.

The Philippines is among a handful of places that will account for more than half of the projected increase in global population through 2050, according to the United Nations.

Balisacan, a prominent Filipino economist, said the Philippines must capitalize on a “demographic sweet spot” in which population growth is less than the rate of growth of the labor force. The country cannot push up gross domestic product unless enough quality jobs are created.

From that vantage point, Balisacan said it’s relatively easy for policymakers in wealthy nations like Japan to address declining birth rates. “Just relax your immigration policy,” he said. “I’d rather have that problem.”

There are some signs of progress. The Philippines’ fertility rate fell to 1.9 children per woman in 2022, according to preliminary government data, though it’s hard to gauge the impact of pandemic-related restrictions. That’s down from 2.7 five years earlier — and below the 2.1 typically viewed as the level at which a population replaces itself from one generation to the next.

As the Philippines aspires for demographic dividend, it has to pay attention to the quality of the workforce, the participation of women and other minority groups and other factors that tend to breed inequality, said Lisa Grace Bersales, executive director of the country’s Commission on Population and Development.

The population commission is working on a five-year action plan targeted for release this quarter or next, according to Bersales. Aside from addressing reproductive health needs, the action plan will bring issues like education, employment, migration and climate change in a holistic approach on demographics, she said.

Family planning also saw a boost after the passage of a landmark reproductive health law in 2012. The legislation expanded access to contraceptives, fertility control, sexual education and maternal care in the Philippines.

In Manila, the nation’s capital, Junice Melgar said more women in poorer neighborhoods now seek out her organization for advice.

“We discovered there was a great need,” said Melgar, executive director at Likhaan Center for Women’s Health Inc., a nonprofit group established in 1995. Since the pandemic, she said, there’s been “an open clamor” for information about contraceptives.

The uptick in public awareness has paid dividends. About half of today’s married Filipino women don’t want additional children, according to the statistics agency. Women in rural areas — where contraception is typically less accessible — had a higher fertility rate of 2.2 children per woman last year, compared to 1.7 in urban areas.

The Marcos government is giving “prime importance” to its youth labor force by allocating funds to hire graduates for internships and helping them look for jobs, according to the Budget Secretary Amenah Pangandaman.

During a speech before investors at the New York Stock Exchange in September, Marcos underscored that push and touted the youth’s readiness to work.

“We are, I believe, the youngest country in Asia,” he said. “And with the graying of other countries around the region, this gives us an advantage.”

(Siegfrid Alegado contributed to this article.)

--With assistance from Suttinee Yuvejwattana.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.