Mar 29, 2023

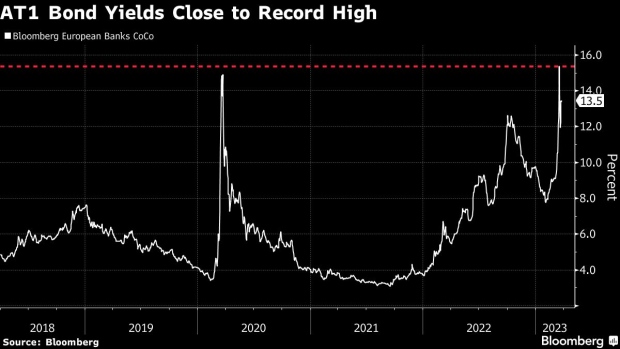

AT1 Yields Near Record Show Lasting Damage From Credit Suisse

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The $256 billion market for additional tier 1 debt is still reeling from Credit Suisse Group AG’s debt wipeout.

For all the soothing words from bank regulators and politicians, the controversial writedown of risky debt as part of the Swiss bank’s emergency rescue has caused big ripple effects. Yields have stayed near record highs and concern is growing that the market convention of buying back AT1s will be broken in the coming months, leaving investors stuck with the debt.

“It’s doubtful that banks will be able to issue new AT1 anytime soon,” ING credit strategist Timothy Rahill wrote in a note. “The AT1 market remains in limbo and the question around the actual value of this product — and subsequently the rest of the liability structure — lingers.”

An index of contingent convertible bonds, or AT1s, issued by European banks had a yield of 13.5% as of Tuesday — down slightly from the record seen after the Credit Suisse wipeout. Yields were as low as 7.8% in February.

“Over the short-term, dollar-denominated AT1s will be a tough sell,” Scott Kimball, chief investment officer at Loop Capital Asset Management.

Banks with AT1 debt face a tough decision balancing the interests of creditors, equity holders and regulators. Given the high cost of refinancing, it may be cheaper for them to skip the first call date — the point at which they normally replace an AT1 bond with a new one — and pay the coupon on the outstanding note.

But that risks angering AT1 holders, who buy this type of debt expecting to be able to switch to a new note at the call. At the same time, calling at any cost may lead to a backlash from shareholders, due to the higher interest. It’s also a sensitive issue for regulators, who can block a refinancing.

About $18 billion contingent convertible notes in Europe have first call dates this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“We still expect most benchmark AT1s in 2023 to be called,” Barclays analysts led by Soumya Sarkar wrote in a note on March 28. “Issuers and regulators will want to follow a more investor-friendly approach given current heightened investor sensitivity.”

Permanent Damage

For US banks, investors are largely shielded from the writedown pain because the big banks generally sell preferred equity, which counts as additional tier one capital but doesn’t have writedown or conversion-to-equity clauses, according to Arnold Kakuda, a bank analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. There’s about $230 billion of institutional and retail preferred debt from US banks outstanding, according to BI.

For investors, there’s still a sense of apprehension about the market. Private wealth may reassess its involvement in AT1s — something that could “permanently impair” demand, according to Barclays’ Sarkar.

“Even if there will be no contagion, the stress and fear will be here,” said Sebastien Barthelemi, Kepler Cheuvreux’s head of credit research. “It will take some time for the market to digest CS and be fully reassured.”

Others, such as Natixis’s co-head of financial institutions debt capital markets Caroline Bryant, expect the AT1 market to come back, but with investors becoming a lot pickier about which bonds they buy.

“Many investors have a short memory and if Russia, Argentina and Venezuela can issue debt, globally systemic banks can sell AT1s,” said Loop Capital’s Kimball.

Adjustments to subordinated bond features are not unusual, and banks will still want to issue the debt for loss absorption, said Nicholas Elfner, co-head of research at Breckinridge Capital Advisors.

“Tier 1 securities have existed in various forms since the mid-1990s,” said Elfner. “Quality of bank capital matters and a thicker common equity cushion is preferable relative to other forms of tier 1 capital.”

--With assistance from Abhinav Ramnarayan.

(Adds US commentary in paragraphs 5, 10, 14-16.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.