Apr 8, 2020

Australia’s Huge Household Debt Threatens to Worsen Recession

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Thuy Pham has run two jobs for much of her working life, and a little over two years ago all that effort paid off when she realized a dream of buying her own home. As the coronavirus shutdowns have deepened, that’s started to unravel: first she was stood down from one job, then the other, and now she’s registering for welfare to help meet mortgage payments.

“I’m scared,” said Pham, who found out she was among the rapidly swelling ranks of unemployed people on the very day she was due to meet her mortgage broker to take advantage of lower interest rates. “Everyone is saying it’ll be six months, but it could actually be longer. I never thought I’d ever be on Centrelink. I’ve always worked my guts out.”

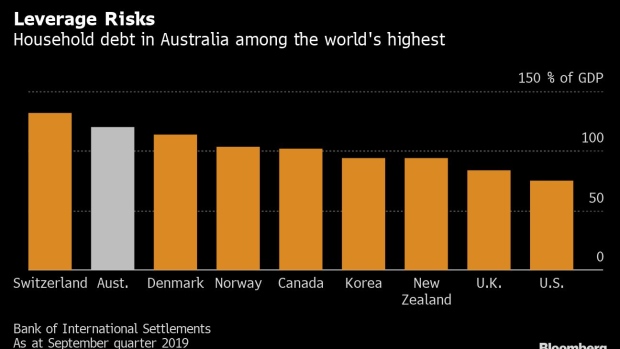

Like many in the workforce, Pham has never really experienced recession due to Australia’s enviable record of almost 30 years without one. But that has come with a less desirable record of highly indebted households and sky-high property prices. This raises the risk that the recovery could taker longer and could increase financial stability concerns if people can’t cover their loans.

Household debt is almost double disposable income, twice the level of the U.S., and well over a year’s annual output. Mainstream economists and the central bank have long argued that while people have jobs and can service those loans, the risk of a hard landing is slim.

Centrelink, which manages welfare payments for the unemployed, has seen queues snaking down streets in recent weeks as tens of thousands people seek support, while others are heading out to the bush in the hope of finding work on farms. It’s reminiscent of 1930, but it’s 2020, and a phenomenon being replicated worldwide.

Australia’s central bank governor is warning of a “very large economic contraction” and unemployment increasing “to its highest level for many years,” an unusually blunt assessment from typically optimistic Philip Lowe.

Job Destruction

“There’s no doubt that we’re going into the greatest job destruction period ever,” said Bob Gregory, a professor at Australian National University in Canberra who specializes in the labor market and has studied the economy for more than half a century. “This looks like the most serious recession-depression we’ve had since the 1930s, and there’s going to be a big income loss in the next six months.”

This is why Australia, together with other high household-debt economies like Denmark, the U.K. and Canada, is offering subsidies to ensure workers have an income and keep them connected to firms. Banks Down Under are offering repayment holidays to help tide homeowners over.

The government last week pledged A$130 billion ($80 billion) in a rescue plan that will subsidize workers’ pay to about 70% of the median wage. While this is positive and important for firms and workers, at about A$1,500 a fortnight, it isn’t going to go a long way in major metropolises like Sydney and Melbourne.

No Panic

Shad Hassen, a 25-year veteran of Sydney real estate, said the government plans have prevented housing spiraling into the chaos of panic selling.

“There’s definitely been a drop in terms of inquiry, and a drop in activity,” said Hassen, a co-founder of The Agency, who sells in Sydney’s inner west. “But without panic selling, prices aren’t going to drop significantly in the very near-term. What happens after COVID, from an economy perspective, that we simply don’t know.”

The unemployment outlook is a center of conjecture. The government’s aim to keep employees tied to their firms, even if they’re not working, will help to suppress the official unemployment number. Still, a number of economists are predicting the rate will surge beyond 10%; more worryingly, few expect a rapid rebound.

Those most directly impacted by a lack of tourists, empty beaches and no activity on the streets are waiters, bar staff, baristas and so forth. While many in such professions are young and probably without mortgages, those that do have loans will probably have little in the way of buffers.

Analysis from the RBA found around two-thirds of home-owner debt is held by the top 40% of income earners. Yet, if the downturn is prolonged and there is a broadening of job losses across other sectors, this would have larger impacts on the housing market.

“Australia’s high household debt was never going to be a cause of a recession, but it would quite possibly magnify the impact of anything else that caused a recession,” said Saul Eslake, an independent economist who has analyzed the Australian economy for 40 years.

“The risk isn’t so much to the financial system that there will be a wave of defaults,” he said. “But rather the risk was to the economy arising from what highly indebted households would do to avoid defaulting, which is substantially cut back their spending.”

And while Australia’s banks are allowing some to defer repayments, they aren’t actually foregoing interest during the period. So it will be added to a borrower’s outstanding principal, which will then require either higher repayments or a longer repayment term by the mortgagee.

No Sub-prime

The nation’s prudential regulator recently conducted a stress test on banks based on a scenario of unemployment reaching 11%. Under this, lenders incurred significant losses and a substantial reduction in capital, but the latter was sufficient to remain above the regulatory minimum.

On top of that, last year’s Royal Commission into misconduct in the banking system didn’t uncover widespread lax lending, easing concerns Australia would be at risk of a U.S.-style sub-prime crisis.

Indeed, two-thirds of Australian mortgagees are also ahead of repayments, as many people kept handing over the same amount even as interest rates fell sharply in recent years.

Slow Recovery

Still, Gregory and Eslake see little chance of a V-shaped recovery. Both expect higher unemployment to persist and key industries like international tourism and education -- accounting for 5% of GDP -- taking time to return to previous levels, if they ever do.

Paul Parks, owner and co-founder of The Bondi Brewing Co., a craft brewer, says the ban on social gatherings and shuttering of venues have brought keg sales “to a complete halt.” Loyal customers have been still been buying his beer at bottleshops and he’s taken to doing deliveries himself.

“Everyone will be doing it tough until they find their own groove and settle into this new way of life,” he said. “So drink local and support local businesses!”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.