Sep 27, 2022

Avaya Loan's Rapid Meltdown Reveals Leveraged Debt Market Risks

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Avaya Holdings Corp. isn’t exactly a household name in US financial circles. It’s a small-ish company in an unglamorous part of the technology business.

And yet it’s possible that years from now, Avaya, a provider of office telecommunications services, will be remembered as one of the first victims of corporate America’s post-pandemic financial reckoning. There are plenty of oddball elements to the story that are specific to Avaya -- like the company’s dramatic earnings revisions and internal investigations -- but in a larger sense, its sudden collapse to the brink of default underscores how quickly the mania captivating Wall Street investors has ended as interest rates soar and the economy cools.

“It’s a crazy situation that you don’t see everyday,” said John Fekete, managing director and head of capital markets at Crescent Capital Group. “There is a lot of litigation risk and uncertainty around liquidity.”

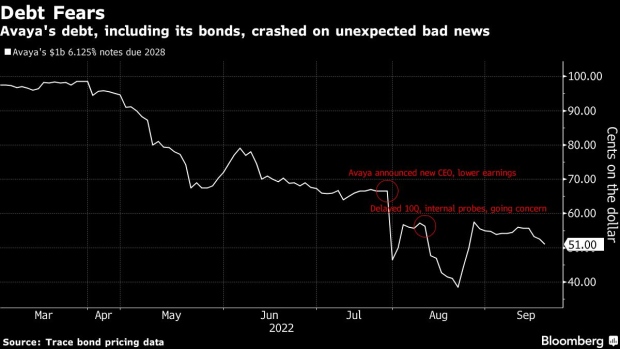

In a matter of weeks, Avaya descended from a highly levered company that could still convince Wall Street investors to lend to it to a deeply distressed company that disclosed “substantial doubt” about its ability to keep operating. It’s something of a cautionary tale of the downsides of the high-risk, high-return leveraged finance world, where, until recently, creditors were eager to lend if it meant a chance at juicy yields.

Alarm Bells

Credit markets were already choppy when Avaya sought to raise new debt in June, but the company didn’t have much of a choice: it had convertible bonds due in 2023 that it needed to refinance. Investors were skeptical of the company’s prospects, and the overall outlook for highly indebted companies. But after being offered a yield of 10 percentage points on top of a benchmark interest rate, they snapped up the new $350 million leveraged loan nonetheless, and the company also sold a chunk of new convertible bonds to private investors.

As is typical, prospective investors were able to speak with Avaya’s executives and bankers Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co., who assured them that the company was on track to reach earnings projections for the year, according to people with knowledge of the discussions.

But weeks after the debt was sold, Avaya dramatically cut its forecasts, and eventually disclosed a significant earnings miss for the quarter through June 30. It fired its chief executive officer and said its prior financial guidance could no longer be relied on. Its debt, including the freshly issued term loan, plunged.

Investors were stuck with millions in paper losses. The newly issued loan was quoted Tuesday at around 66 cents on the dollar, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, while its older convertible bonds were quoted at about 45 cents.

Taking Action

The timing of the debt deal, in light of the later earnings revelations, spurred concerns from investors around Avaya’s governance and internal controls, according to creditors and industry observers. Groups of investors fuming over the debt’s collapse quickly banded together and brought in lawyers to explore their options.

“Whether it’s stupidity, whether it’s simple human oversight, or whether someone did something rather naughty,” said Anthony Sabino, a law professor at St. John’s University and attorney focused on litigation, “then Avaya has to know that as well because they have to be prepared for the allegations that will be launched against them.”

“The creditors are going to get to the bottom of this one way or the other,” Sabino added.

Some of the lenders’ advisers have signed confidentiality agreements to assess the financial health of the company and begin formulating debt plans, the people said.

While the company delayed reporting public results, Avaya last month posted some financial information in a private data room, and said it’s meeting reporting requirements for its term loans, the people added.

“That could set a pretty bad precedent where a company is able to go out and solicit financing with public financial information and then not be able to provide financials,” said Matt Zloto, a senior analyst at CreditSights.

More recently, Avaya’s advisers are examining an exchange offer for the convertible notes due 2023, including swapping into a secured note and extending the maturity, the people said. The company could also transfer valuable intellectual property to an unrestricted subsidiary and use that to issue new debt, they said.

A group of new lenders had asked the company to place some $221 million from the loan sale in escrow in lieu of paying off the convertible notes now. The old unsecured convertible bonds rank below loans in line for repayment in a bankruptcy.

Representatives for Avaya, JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs declined to comment.

Vicious Cycle

Meanwhile, individual equity investor Theodore King emerged as Avaya’s biggest shareholder. King, who owns a roughly 15.4% stake as of Aug. 22, said he believes the company’s new Chief Executive Officer Alan Masarek can execute a turnaround once the company reaches a deal with its creditors.

“The vast majority of creditors are seeking to engage with the company constructively in order to put the issues to bed swiftly,” King said.

Avaya’s move to a cloud and subscription business means it’s booking revenue based on monthly payments, rather than upfront payments. That ostensibly creates long-term stability and dependable revenue, as corporate clients are less inclined to switch to different software or devices with monthly or annual payments.

The company’s last earnings miss was due to lower-than-expected subscription revenues, which could signal customers growing jittery over the company’s near-term debts, Masarek said on the August earnings call.

“Ultimately the question is how much of a mess are third-quarter results, whether it’s a one-time issue or if it indicates future performance,” said CreditSights’ Zloto .

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.