Dec 15, 2018

Bandits Twin With Floods to Shatter Nigeria's Food-Export Dreams

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Nigeria dreamed of a farming renaissance that would slash food bills and rival oil as its top export. It didn’t count on gun-toting herdsmen, heavy floods and a persistent Islamist insurgency.

That perfect storm of insecurity and poor planning has hobbled one of President Muhammadu Buhari’s flagship pledges -- to cut an annual $22 billion in food imports -- just as he gears up for elections in February. It’s prolonging the West African nation’s reliance on crude revenue, a downturn in which sparked a 2016 recession.

There’s a “lack of strong public governance and political will to take important decisions in the areas of security,” said Femi Soneye at Mount Olive LLC, a Maryland-based company that advises Nigeria’s agriculture ministry. The government has also struggled to provide the support promised to farmers, he said.

Reviving wheat and rice production would help restore farming to the economic primacy it had before Nigeria’s 1970s oil boom. As crude revenue grew and the country became Africa’s top producer, large-scale agriculture languished. Today in Africa’s most populous nation, petroleum accounts for 90 percent of foreign-currency earnings and two-thirds of government income.

Turnaround Promised

Buhari’s 2015 election and the dramatic fall in crude prices the previous year fueled plans for a turnaround. New varieties of wheat and cocoa -- already Nigeria’s largest export after oil and gas -- were to be introduced; farmers were promised better access to credit, inputs and equipment.

But agricultural data show little has changed.

The world’s 10th-largest wheat-buyer, Nigeria pledged to cut imports by 60 percent by 2025 by bringing in varieties that can thrive in warmer climates. Output, though, hasn’t shifted from an annual 60,000 metric tons. That’s dwarfed by the more than 5 million tons it shipped in 2017 from Russia and the U.S., according to the Agriculture Ministry.

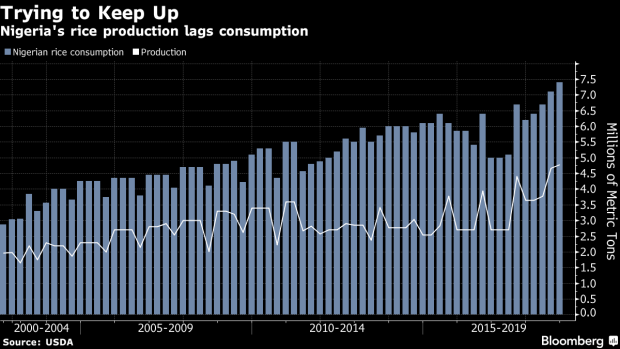

Processed-rice production is more disputed. The ministry forecast 38 percent growth this year to 6.5 million tons and officials say foreign rice arriving at ports has dropped 95 percent because of new levies. Central bank governor Godwin Emefiele this month said $21 billion has been saved, without giving a time period.

Rice Smuggling

A U.S. Department of Agriculture report in November said different, estimating 2018 rice output at 3.7 million tons, with imports jumping 12 percent. Rice-smuggling has also become big business for Nigeria’s neighbors such as Benin.

The main reason for the failed revival: insecurity.

Central Nigeria, the country’s breadbasket, has been roiled by more than two years of conflict as herders who traditionally grazed their cattle on plains in the semi-arid Sahel zone move south, clashing with farmers. About 1,300 people were killed in the first half of 2018, prompting the Brussels-based International Crisis Group to dub it the nation’s biggest security threat.

The northeast -- a major wheat producer -- is plagued by violence by Boko Haram. The Islamist group’s nine-year campaign to impose religious law has killed thousands of people, forced others into the cities for refuge and taken a heavy toll on farming.

“People who are supposed to enhance agriculture are continuously migrating from areas where they can get killed,” said Wale Adeboye, coordinator of the Terrorism Research Initiative in Maiduguri, a northeastern city.

Natural disasters played a part too. Heavy rains since 2016 have washed away rice, corn, wheat and sorghum planted beside Nigeria’s major rivers.

Cocoa Losses

Cocoa took some of the biggest losses. In 2014, authorities planned to quadruple output to more than 800,000 tons per year by introducing hybrid seedlings. After farms were ravaged by rains and disease, the government’s 2018-19 forecast is just 300,000 tons.

Most farmers have lost at least half their crops to disease, according to Solomon Williams, coordinator of the Cocoa Farmers Association of Nigeria. Adding to their woe, growers now have to pay full-price for seedlings, fungicides and herbicides that the government formerly subsidized, he said.

Farmers have broadly welcomed the government initiatives, but many say they falter at implementation. The central bank-backed Anchor Borrowers plan, for instance, is pledging 220 billion naira ($605 million) in loans for rice and wheat farmers.

“The problem we are facing as farmers is that we don’t get money on time,” said Sanni Musa, a rice farmer in Kebbi in the north.

Unreliable electricity supplies and poor transport links have also hit harvests and discouraged investors.

“There are good policies in place for the growth of the agricultural economy,” said Victor Iyamah, president of the Federation of Agricultural Commodities Farmers Association of Nigeria. “The lack of growth has to do with policies which get scuttled at the implementation stage.”

--With assistance from Paul Wallace.

To contact the reporters on this story: Ruth Olurounbi in Abuja at rolurounbi4@bloomberg.net;Tolani Awere in Lagos at tawere@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Karl Maier at kmaier2@bloomberg.net, Dulue Mbachu, Michael Gunn

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.