Jun 4, 2019

Bank of Canada's lessons for the Fed: Bar to change is high

, Bloomberg News

What the Fed could learn from the Bank of Canada

Don’t bet on Federal Reserve officials to overhaul how they target inflation if the experience of counterparts at the Bank of Canada is anything to go by.

As Fed policy makers meet in Chicago to debate whether to change their inflation target, they have been sharing notes with counterparts north of the border where mandate reviews have been regularly undertaken over the past two decades.

The lesson they’ll learn is that the bar to change is high.

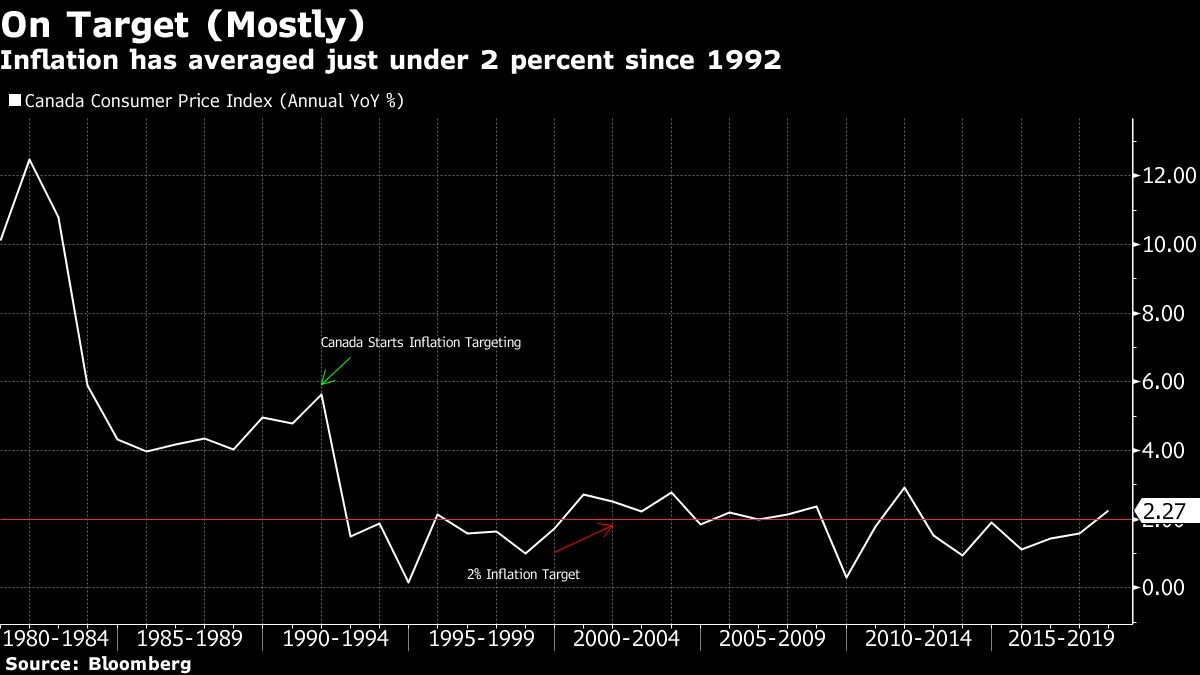

Every five years, the Bank of Canada reassesses its monetary policy guidelines, not unlike what the Fed is currently doing, including a conference this week on alternatives. While the research surrounding Canada’s reviews has been serious, the end result each time has only been minor changes.

The biggest tweak, made in 2011, gave the Bank of Canada more time to reach its target. The underlying objective -- to focus exclusively on price stability and use 2 per cent inflation as an operational guide -- has been largely untouched.

So why hasn’t the case for change been more compelling?

Officials at the Bank of Canada, whose next mandate renewal takes place in 2021, boil it down to a few things:

- The system is not perfect, but the framework has been largely successful even with the recent difficulties in hitting the target. Price pressures and inflation expectations are stable, and economic cycles over the past two decades have been less volatile than has been historically the case

- One of the biggest benefits of inflation targeting is it’s much easier to communicate, and for people to understand, than more complex approaches

- Perhaps more importantly is an acknowledgment that there is a false precision to the whole business of inflation targeting. Economics isn’t an exact-enough science to really allow them to get it perfectly, which is why Canadian policy makers are happy to allow inflation to move within a range -- 1 per cent to 3 per cent -- and would become worried only if they see a real risk of the band being breached. The 2 per cent “target” is simply the midpoint.

“For now what we’ve got is the inflation target and it’s done a good job for us,” is how Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz recently put it.

On the idea of average inflation targeting being touted widely, for example, Poloz says it makes a lot of sense theoretically “but in practice, I’d need to be persuaded myself.”

“The ability to let it cruise above 2 and know exactly when to prevent it from continuing on towards 3 is a lot harder than rocket science,” said Poloz. It’s “really hard to pull off and risky on the upside.”

Open to Change

That doesn’t mean things won’t change. Poloz and his main deputy overseeing the review, Carolyn Wilkins, seem to be open to new ideas, particularly given how monetary policy is becoming increasingly constrained by low interest rates and inflation. That’s a world where the central bank has limited firepower to fight a recession, even as cheap money threatens to fuel the financial imbalances that led to the last global crisis.

As a result, the latest review underway at the Bank of Canada seems to be the most ambitious yet. Alternatives under consideration include raising the inflation target, targeting the price level, developing a dual mandate, targeting nominal GDP and even average inflation targeting.

Yet, Canadian monetary policy makers are also quick to point out that there are limits to what central banks can do to solve all the economy’s ills. Government policy too, they point out, has an important role, particularly in tackling structural issues.