Aug 12, 2022

Banks Balk at Biden Team’s Anti-Redlining Plan, Teeing Up Clash

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Banks are pushing back on key parts of Washington’s latest bid to get them to boost lending to lower-income communities, setting up a policy clash with key Biden administration regulators and Democratic lawmakers.

Two of the industry’s top lobbying groups have come out against a proposal to change how firms are judged on efforts to provide credit to historically under-served groups. The stakes for tweaking the decades-old standards are high because weak scores could potentially hamstring expansion and critics say banks have been graded too easily.

The issue is also fraught politically. Top Democrats in the House and Senate want regulators to take a tough stance to ensure that lenders comply with the Community Reinvestment Act, a 1977 law that was intended to address redlining which historically kept Black and Latino communities from getting loans.

The proposal represents “a major change” because bank regulators haven’t been seeking big overhauls beyond responding to the 2008 financial crisis, said Mehrsa Baradaran, a University of California, Irvine law professor and author of “How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation and the Threat to Democracy.” “The CRA has been needing to be updated for a long time,” she said, adding that the plan could go further but was a good first step.

The rule rewrite effort, which was in part driven by Federal Reserve Vice Chair Lael Brainard, has been billed as a necessary reboot for an age of online banking. Before taking office, Michael Barr, the central bank’s new vice chair for supervision, said in May that he was “very encouraged” by the plan.

But, the American Bankers Association and the Bank Policy Institute, two of the most powerful financial trade groups in Washington, say parts of proposal might actually make things worse. The industry is also confronting a push by Democratic lawmakers and progressive groups to get regulators to expand the proposal to include the demographics of communities as part of its assessments.

Advocates of that approach point to data showing that many non-White communities remain under-served more than four decades after the passage of the CRA. For example, Black borrowers in low- and moderate-income areas in most major US cities receive disproportionately few loans, according to a 2022 analysis from the Urban Institute, a DC-based non-profit.

The ABA and BPI say that they’re concerned the proposal could make it so difficult for banks to achieve a high rating in evaluations that some lenders may pull back on their efforts. The groups also say a key component of the suggested standards would be weighted too heavily, potentially skewing banks’ service offerings. BPI added that it was concerned that aspects of the plan “would be needlessly sweeping, complex, and punitive in its application.”

Federal regulators last significantly updated the rules for implementing the CRA during Bill Clinton’s presidency. After failing to agree on an overhaul during the Trump administration, the Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. jointly proposed changes in May. All three declined to comment on individual feedback they have received.

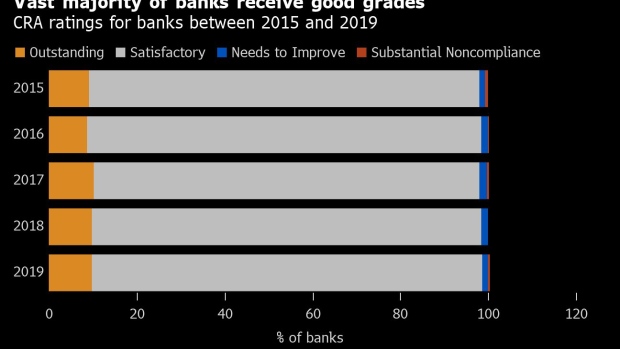

When the plan was announced, Rohit Chopra, a FDIC board member who also leads the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, derided “grade inflation” in banks’ scores for complying with the CRA. Critics have also pointed out that many communities continue to be under-served, despite banks’ high passing rates.

The BPI and ABA reserved some of their strongest objections for how the government plans to evaluate big lenders with at least $2 billion or more in assets. While banks with more than $600 million in assets would face a range of new metrics under the plan, lenders with $10 billion or more in assets would also face an additional slew of new data collection and disclosure requirements.

The groups said regulators were eyeing a “one-size-fits-all approach” for large banks that ignores differences across the industry. At a minimum, they want the government to give banks two years instead of one as was proposed in May to comply with the new requirements.

The period for groups to submit comments on the plan ended Aug. 5. The Fed, FDIC and OCC will now review feedback, make changes and then vote again to finalize the plan. After that, if industry groups are still unhappy, they could sue.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.