Mar 12, 2020

Bear Market Signals Over 80% Chance of Recession Hitting U.S.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- You can search for years and get nowhere, examining stock gyrations for clues about economic growth. But when U.S. benchmarks slide into a bear market, that’s a different story.

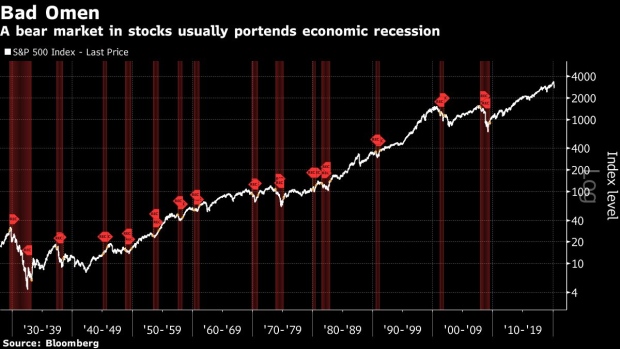

Thirteen times the S&P 500 has completed the requisite 20% plunge in the last 93 years. In just two of those episodes did the American economy not shrink within a year: 1987 and 1966. It works the other way around, too. Among 14 recessions over the span, only three weren’t accompanied by a bear market.

“That’s what people have to be realistic about,” said Jerry Braakman, who helps oversee about $1.9 billion as chief investment officer of First American Trust, in Santa Ana, California. “We are in unknown territory, it could get worse. As the government takes action, people will be thinking about great-financial-crisis situations. People are panicking.”

It’s a common adage: the stock market isn’t the economy. But the saying loses its pull at times like this, both because of the force it takes to knock the market this hard, and the impact of equity losses on consumer psychology. Also: usually the market warns something is awry long before economic growth goes negative.

The spreading coronavirus and historic oil-price shock have ushered in the most volatile period in markets since the financial crisis, and a Bloomberg Economics model places the odds of a recession over the next year at 52%, the highest since 2009.

According to JPMorgan’s John Normand, financial markets across assets have priced in an 80% probability of recession happening -- the highest it’s ever been without the U.S. actually being in one (and we may already be). With the Cboe Volatility Index, known as the VIX, surging to the highest since 2008, and massive swings and market-wide trading halts essentially becoming the norm, investors are questioning what’s to come.

Doug Ramsey, chief investment officer at Leuthold Group, takes the view that a drop in the stock market not only reflects a dire outlook for growth, but also has the potential to hurt American confidence and spending. His firm trimmed its equity exposure last week.

“For many months we’ve argued that fragile consumer and business confidence could be shattered by even a moderate market setback of 8-10%, finally sending the economy into recession,”’ he wrote in a note to clients. “It is very likely this market setback will prove the final death blow to the longest ever economic expansion.”

A Bloomberg Intelligence model shows equities are close to pricing what the average U.S. recession looks like. Down to 17 from above 22, the S&P 500’s trailing P/E ratio has contracted close to 24%. That’s just short of the average drop of 24.5% during the past six growth scares, according to strategists led by Gina Martin Adams -- and above the average of 21% excluding the 2008 crisis.

Forecasters across Wall Street are taking a knife to their predictions. Goldman Sachs’ David Kostin Wednesday called for an end to the bull market and called for earnings to drop at least 12% in each of the next two quarters, just before the Dow closed down 20% from a high, ending the bull run.

The S&P 500 fell 7% to 2,549 Thursday morning in New York, triggering market-wide circuit breakers for the second time in a week. According to Lori Calvasina, the head of U.S. equity strategy at RBC Capital Markets, if 2,700 on the S&P 500 doesn’t hold, the move will likely indicate that investors are pricing in a recession.

During economic downturns going back to the 1930s, the S&P 500 has on average posted a 32% peak-to-trough decline, RBC data show. From the S&P’s record a few weeks ago, a decline of this magnitude would push the index to 2,302.

Still, Calvasina doesn’t see a recession in the U.S. as her base just yet. She lowered her year-end forecast Thursday for the S&P 500 to 3,279 and cut her estimate for S&P 500 EPS by $9 to $165. That would imply a gain of about 1.5% for the benchmark this year and a second straight year of zero profit growth. The most recent rout has been reminiscent of post-Financial Crisis growth scares, such as those in 2011 and 2018, and a rebound later in the year could be “fast and powerful,” she wrote to clients.

UBS strategists led by David Lefkowitz also cut their profit forecast for companies in the S&P 500, estimating no growth this year. They reduced their year-end target to 3,200 from 3,400, about in line with RBC’s Calvasina’s. But they too said a deeper hit to the economy can’t be ruled out with containment measures in the U.S. “behind the curve.” In the case of a mid-year recession, S&P 500 EPS could fall to $145, resulting in a year-end price target of 2,500.

“We have less confidence in our forecasting abilities this year than in any in recent memory,” Lefkowitz wrote in a note.

He’s not alone.

“Investors are really dealing with the unknown as far as how long this lasts -- That’s the key element,” said Chris Gaffney, president of world markets at TIAA. “The risks continually rise and the impacts widen -- the worst is yet to come.”

--With assistance from Vildana Hajric and Elena Popina.

To contact the reporters on this story: Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net;Lu Wang in New York at lwang8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.