Nov 13, 2021

Belarus Strongman’s Economic Lifeline Turns Out to Be Europe

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Belarus strongman Alexander Lukashenko has faced more than a year of condemnation from the West for his post-election crackdown at home, including sanctions from Europe. For all of that, trade is booming.

Exports to the European Union have almost doubled, rescuing the economy from recession and helping keep Lukashenko afloat. The bloc in June targeted petroleum products and potash, a substance mostly used in fertilizer and which Belarus produces in abundance, but stopped short of a full ban.

Lukashenko is now upping the ante with Europe, threatening to block the transit of natural gas supplies from Russia to Poland and beyond. He’s deployed migrants from the Middle East as a political weapon, ferrying them to his western borders and creating havoc with neighbors like Poland and Lithuania.

The EU is weighing further penalties as a result, but those are unlikely to include hefty restrictions on trade.

The feud is part of a broader tangle between the bloc and Vladimir Putin. The Russian president has backed Lukashenko against allegations he rigged his election win last year, and the two put meat on the bones of plans for economic and political integration in a Nov. 4 deal.

Poland has accused the Kremlin of masterminding the border chaos. The U.S. meanwhile is warning European officials it believes recent Russian troop movements could presage a renewed invasion of neighboring Ukraine. The Kremlin has dismissed both claims.

U.S. Warns Europe That Russia May Plan Ukraine Invasion

EU-Belarus trade data belie the tensions and sanctions.

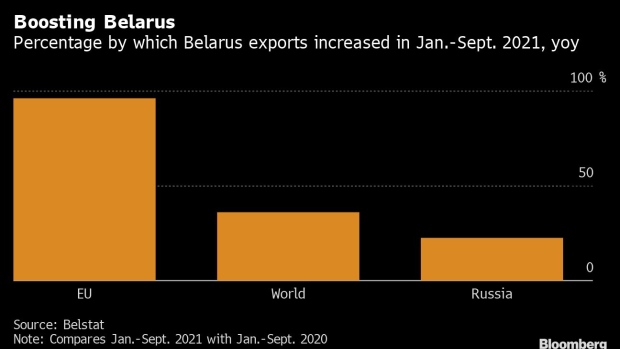

In the first three quarters of this year, the bloc imported 96.1% more from Belarus than in January-September last year, according to Belstat, the official Belarus statistics agency.

The EU’s statistics agency Eurostat doesn’t have a full set of comparable figures. But according to its data, imports from Belarus to the 27 EU states grew 58% in the year to August, compared to the same period in 2020. Any disparity is likely due to different methods each uses for counting exports, such as goods passing through European transit hubs to third countries.

Exports from Belarus to Russia have grown too, but at less than a quarter of the pace the Belarus data show for the EU. It’s likely — if hard to prove as the Belarus government has classified the data — that sales of refined petroleum and potash, singled out by current EU sanctions, contributed to the boom.

The net result: An export-led recovery for Belarus that produced 5.8% growth in gross domestic product in the second quarter, compared to a year earlier, and 2.7% growth in the first three quarters.

Other economies in the region are also bouncing back from the hit they took in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the turnaround for Belarus is bigger than expected. After last year’s political turmoil, economists including at the World Bank were predicting a deepened recession.

Crowds, at times in the hundreds of thousands, had for months been protesting Lukashenko’s claim to have won the August 2020 election. When he cracked down, throwing thousands into jail, the EU and U.S. threatened sanctions. Added to the challenges from the pandemic, it all spelled bad news for the economy.

Instead, says Dzmitry Kruk, senior fellow at the Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Center, Belarus is among the few countries “where exports of most product items have fully recovered from the pandemic shock between end-2020 and early 2021.”

In one sense, there’s no miracle required: Lukashenko has survived by wiping out opposition at home, securing Russian backing and – when it comes to economics – luck.

The U.S. and EU sanctions only took effect in June and were less punitive than billed. Restrictions on EU imports of potash from Belarus, for example, were crafted to exempt the grade it mainly produces. Belarus is the world’s third-largest supplier, after Canada and Russia, according to Canadian government data. In negotiations around further sanctions, according to an EU diplomat familiar with the talks, Belgium and Italy are blocking any expansion on potash, as well as petroleum measures. The focus is on grounding Belarus’s national airline, Belavia, already blocked from the EU, and pressuring other airlines to stop carrying migrants to Minsk from the Middle East.

Turkey Agrees to Curb Migrant Flows to Belarus Under EU PressureLike other commodity exporters, Belarus benefited from the boom in global demand and prices that followed 2020’s Covid-19 related lockdowns, including for fertilizers and refined petroleum. Its biggest exports to the EU are wood and metals, also in high demand.

In addition, Belarus gained from supply chain disruptions that reduced competition from Asia, boosting demand for Belarus products, including furniture and machinery. It didn’t hurt that the International Monetary Fund decided in August to give Belarus its almost $1 billion share of a special distribution, propping up the nation’s foreign currency reserves. Even Lukashenko’s pandemic-denying refusal to impose lockdowns may have supported growth, according to a World Bank report. That sequence of events surprised pretty much everyone, says Kruk. Domestic demand and investment did decline this year, but the surge in exports outweighed those losses. Worldwide, exports rose 36.1% in January to September, compared to the same period in 2020, according to Belstat. Much of the population continues to contest Lukashenko's legitimacy and there's no guarantee his luck on the economy will last. As sanctions begin to bite, the World Bank now forecasts the economy will shrink by 2.8% in 2022.

The weak outlook may help explain Lukashenko’s attempt to get sanctions lifted. With few other cards to play, he’s flying in migrants from war-torn countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan, with the sole aim of forcing a political crisis at the EU’s border that he can then offer to end, according to Pavel Slunkin, a former Belarus Foreign Ministry official who is now a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. The EU is unlikely to agree, but that won’t stop Lukashenko, says Slunkin.

“Lukashenko is the kind of guy who never steps back,” he said. “He tries to do what worked before, and when he tried to manipulate the EU before, it always worked.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.