Sep 3, 2020

BHP’s Road To Reduced Emissions Should Be Electric

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As oil companies flesh out plans to cut carbon emissions, their peers in the mining sector risk being left behind.

BHP Group, Rio Tinto Group and Vale SA are already among the world’s largest emitters, thanks to the vast amounts of carbon spewed out turning their key product of iron ore into steel. Among producers with listings on major developed exchanges, only Royal Dutch Shell Plc sits higher than the big three miners in terms of so-called Scope 3 emissions. (This describes pollution generated when a company’s products are used, such as when gasoline is burned in a car or steel is produced in a mill. It comprises the vast majority of total emissions in the resources sector.(1))

Oil companies are already working to address that issue. Eni SpA, Shell, Total SE and Repsol SA all have plans to reduce the emissions intensity of their products by about a third by the 2030s, with sharper cuts to 2050. BP Plc has signed up to a more ambitious target, reducing oil production 40% by 2030.

The big iron miners, on the other hand, have made do with only the vaguest of promises. Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. refuses to even disclose its easily calculated Scope 3 total. BHP’s announcement of its plans Sept. 10 is likely to set a benchmark for other companies. New Chief Executive Officer Mike Henry has good reason to be bold.

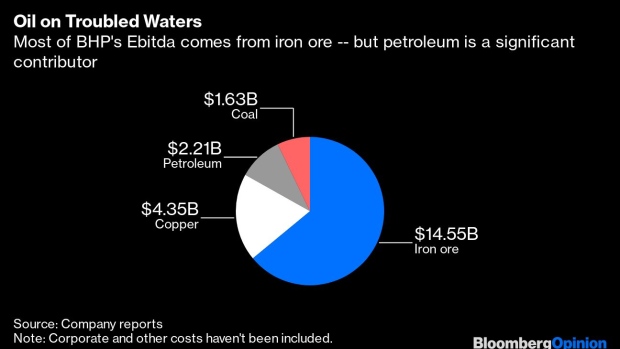

To see why, it’s worth considering what makes BHP unique among big miners. Unlike its peers, the company also has a significant petroleum business, with gas comprising about 55% of its 109 million barrels of annual oil-equivalent output. Producing another fossil fuel might not seem the most obvious way for BHP to decarbonize — but its expertise in the industry could go a long way toward reducing emissions from its steel mill customers.

To make more than a marginal reduction in the 7% to 8% of global emissions that come from steelmaking will involve either a breakthrough in capturing carbon emissions and storing them underground, or a switch from making metal in blast furnaces to using electric arc furnaces. Understanding petroleum geology and engineering will be a major advantage in both cases.

Carbon storage has never lived up to the hype. But to the extent that it’s viable anywhere in the world, it’s where CO2 is injected into underground petroleum reservoirs, usually to drive more oil and gas to the surface. If BHP’s customers are to go down that route, it’s the only major miner that could make money from being part of such a solution.

As we’ve argued, the more likely approach is a switch to arc furnaces, which use electricity rather than coal to melt their metal. A growing mountain of steel scrap in China, combined with likely prices on carbon emissions and greater ability to match output to demand, should see them replacing an increasing number of blast furnaces over the coming decades. BHP itself sees the share of blast furnaces declining from 70% of global steelmaking capacity to between 55% and 60% by 2050.

Mining companies genuinely motivated to halt rather than advance climate change should see a great opportunity in this shift. The key commodity for a world making steel without blast furnaces would be direct reduced iron, which can be produced by burning off the oxygen in iron ore using natural gas or hydrogen — probably in the easily transported form of hot briquetted iron, or HBI. BHP had bad experiences with this product two decades ago, but the technology hasn’t stood still and demand is forecast to rise rapidly.

If the four miners that account for more than two-thirds of iron ore in the seaborne market committed to converting a rising share of their output to HBI, then they’d be nudging customers to decarbonize their steel mills, while selling a product that changes hands for about three times the price of iron ore. So far, though, only Vale has shown much interest.

As a petroleum producer in the North West Shelf off the coast of the iron-rich Pilbara region, BHP is well-placed to provide the power an Australian HBI industry would need — first via “blue hydrogen” made from methane with carbon capture, but ultimately with “green hydrogen” made by splitting water molecules with renewable power and transported via legacy natural gas infrastructure.

Such a switch wouldn’t be good news for BHP’s coking coal business, which is heavily dependent on blast furnaces retaining their market share. Becoming part of the solution, though, would allow the company to manage the decline of coking coal while making money from the technology that will disrupt it, rather than crossing its fingers that the world will fail to address climate change.

The mining industry has played its cards well convincing environmentally minded investors that there’s no alternative to blast furnaces. That’s helped miners avoid the opprobrium, divestment and capital drought that's hit thermal coal of late — but with the world's fossil fuel-free steel mill starting operations this week, it’s becoming an increasingly untenable position.

BHP’s reluctance to accept what was going to happen to the coal power industry in the 2010s cost its shareholders dearly. Is it going to make the same mistake again with steel?

(1) Some oil companies, including Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp., don't declare their Scope 3 emissions. BP would have comparable figures to Shell if it equity-accounted the emissions from its stake in Rosneft Oil Co.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.