Sep 14, 2021

Biden’s Allies Shy From Taxing Rich, Eroding Inequality Promise

, Bloomberg News

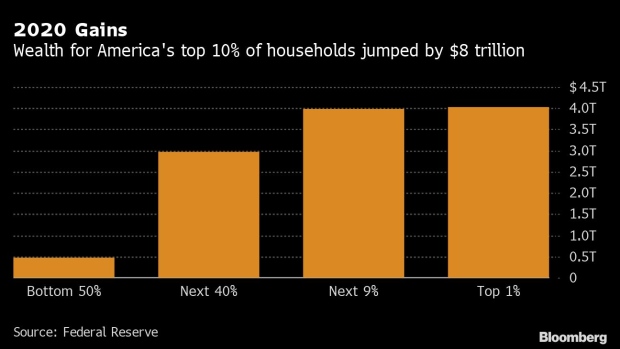

(Bloomberg) -- Joe Biden’s push to ramp up taxes on the wealthy is getting diluted by his Democratic allies in Congress, undermining the president’s chances of fully delivering on his 2020 campaign pledge to curb America’s widening inequality.

A blueprint that the House Ways and Means Committee will begin voting on Tuesday, prepared by Democratic members and staff of the panel, scaled back some of the most ambitious elements of the Biden administration’s pitch released in May.

The changes reflect the political reality of a Senate that requires moderate Democrats to vote en masse for the final package, given the razor thin margins of the party’s control of the chamber. The cost: support from progressives needed to fire up the electoral base in 2022, and a more concerted effort to address inequality that evidence shows is damaging the U.S. economy.

Biden’s move to tax rich families on inherited assets at the time of transfer -- ending the so-called step-up in basis measure -- is absent from the House plan unveiled Monday. His top capital gains tax rate of 39.6% gets weakened to 25%. There is a 3% surtax on incomes exceeding $5 million, but the principle of bringing levies on investments more into line with wage-earners’ incomes is eroded.

While Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden hinted at addressing step-up in basis, such a gesture faces opposition from moderate Democrats in the upper chamber. Farm-state lawmakers have voiced particular concern about doing away with tax-free transfers of inherited assets, even though family farms were specifically marked out as an exception by Biden.

Remaining ‘Hole’

“The biggest area where it falls short compared to Biden is changing the capital gains tax base, which is key to making sure billionaires pay taxes on those gains and making sure those gains don’t go un-taxed entirely,” said Seth Hanlon, who served as a tax policy adviser in the Obama administration. “There is still this hole in the tax code that allows wealthy people to avoid taxes on their gains entirely.”

Hanlon, now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, said the House plan, which includes increases in a range of levies on companies, does mark a “very large step forward.”

Inequality is also addressed through strengthened programs to aid middle-class and lower-income households, all part of a giant bill currently valued at $3.5 trillion over 10 years. Congressional panels are now crafting the legislative text for the various components, which include expanded child tax credits and enlarged outlays on health care and education.

Biden’s Build Back Better plan, dating to the presidential campaign, expressly promised to reverse the Republican tax cuts from 2017 and ensure the wealthiest Americans paid their fair share.

One White House official said that the administration expected many twists and turns in the coming weeks as congressional Democrats debate the best way to raise revenue, and pointed out that the Senate Finance Committee has its own own proposal coming.

The official declined to specify what alternatives it would back to address raising taxes on the ultra-rich if the administration’s proposals on step-up in basis and a 39.6% top capital gains rate don’t make it through the lawmakers’ discussions.

The criteria the administration is using to evaluate lawmakers’ ideas are whether they reverse what Democrats regard as the worst parts of the 2017 tax overhaul, and whether they force larger companies and the highest-income Americans to pay more.

That marker is something short of what progressives want. Even Biden’s proposals excluded the kind of annual wealth tax that Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders endorsed on anyone with more than $50 million in assets.

“Democrats still have not gotten religion on the tax fairness issue,” said Frank Clemente, executive director of the left-leaning group Americans for Tax Fairness. “If we can’t pass a tax bill that strikes a modest blow at the accumulation of dynastic wealth, what does it say about the Democratic Party and whose side are they on?”

Raising levies on powerful, well-connected constituents has always been a tough battle -- the last comprehensive set of tax increases, in 1993, was enacted with a vice presidential tie-breaking vote in the Senate. Lawmakers this time are facing an intense lobbying effort from a raft of major business groups and newly formed coalitions to weaken proposal.

Even though Biden’s plan to eliminate step-up in basis included exemptions, opposition from groups including the National Corn Growers Association has been vocal. The administration’s package exempted from taxation any family business or farm passed down to heirs and would tax the increase in the value of the business or property only when it is sold, or stops being run by the family. Biden’s plan also exempts the first $2.5 million in gains from family farms from taxation.

One outside coalition, run by former Heidi Heitkamp, a former Democrat senator from North Dakota, argues that the proposed tax changes would still hit ordinary Americans like farmers or those who run smaller family businesses. She said the Biden proposal has generated deep skepticism among farm owners and rural business owners who fear the provision would erode land values or that the exemptions could later be weakened.

“When you think about this in the long run, is the revenue that would be raised commensurate with the political liability you’re taking on?” Heitkamp said in an interview. “To think there is no political liability, that may be true in downtown Queens, but it’s not true in states like North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, in rural districts, in swing districts.”

‘Smoke Screen’

Senator Jon Tester of Montana, a Democratic moderate, said through a spokesman that none of the inheritance-transfer tax proposals he has been offered so far are acceptable and he will continue to oppose them on behalf of family farms, ranches and small businesses.

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, however, wrote in a recent opinion piece that lobbyists were using “American farmers as a smoke screen to keep a system that allows the rich to pass on their wealth tax-free.”

The tax increases pitched by the House committee would raise revenue by $2.1 trillion over 10 years, according to Congress’s official scorekeeper. If those increases get further diluted, the spending side of the so-called reconciliation bill -- which bypasses a filibuster, allowing for it to be approved without Republican support -- may also have to be trimmed. Senator Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat from West Virginia, has already warned he won’t vote for a $3.5 trillion bill.

“It’s still a very significant change -- just how significant depends on the political bargaining,” Jason Furman, a senior economic adviser to former President Barack Obama, said of the tax provisions under consideration. Furman, now a professor of economic policy at Harvard University, predicted in the end “something very large will come together” on the tax-fairness front that would amount to “the most significant effort to reshape inequality in generations.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.