Dec 9, 2022

Biden’s Labor Cred Risks More Cracks Over Pacific Ports Fight

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- President Joe Biden celebrated avoiding a disaster when the government stopped a railroad shutdown, but another economy-threatening labor dispute looms on the West Coast.

Dockworkers at some of the nation’s busiest ports have worked without a union contract since July 1 and there has been little progress toward a new deal. Negotiations resumed after Thanksgiving and both sides have vowed to stay at the bargaining table until a new pact is reached.

A new agreement might not happen until January or early February, Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka, who isn’t a part of the talks, said in a recent interview with Bloomberg News, adding he is “optimistic” about avoiding a service disruption.

But a collapse in talks between the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, representing 22,000 workers, and 70 companies comprising the Pacific Maritime Association would risk a work stoppage that could snarl US supply chains still reeling from pandemic-era disruptions and fuel inflation.

The Biden administration believes there would be serious economic consequences if negotiations go south, according to a senior official.

Key West Coast maritime hubs have already experienced cargo slowdowns in anticipation of disruptions, and a complete shutdown of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach alone could cost the US economy about $500 million a day in lost trade, according to the National Association of Manufacturers.

Political Challenge

The situation presents a political challenge for Biden, who frustrated key union and Democratic allies by signing legislation to stop a potential rail strike with an agreement that did not include paid sick leave, a key labor demand.

Unlike the rail dispute, in which federal law empowered Congress to prevent a strike, the president could avert a work stoppage without lawmakers’ involvement if port negotiations break down by invoking the Taft-Hartley Act, a Cold War-era law allowing the government to call for an 80-day cooling off period to end labor impasses.

But doing so could spark further criticism of Biden from the left, which questioned his pro-union bona fides during the freight-rail dispute. The last time a president invoked the law’s emergency provisions was 2002, when President George W. Bush used them to end a lockout that resulted in an 11-day shutdown of 29 West Coast ports from Washington State to San Diego.

One industry official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said Biden would likely have to rely on his moral authority, rather than ordering dockworkers to stay on the job using controversial powers that could antagonize union allies.

“Both parties have been working hard to reach a deal and they have made it clear that they are committed to staying at the table and negotiating in good faith,” said Erika Dinkel-Smith, the White House director of labor engagement. “The administration is in close contact with each side and we’re confident in their ability to reach an agreement.”

Given the complexity of the contract and the number of different ports and jobs involved, the negotiations may still take months to come to a head or reach a resolution, said Larry Cohen, former president of the Communications Workers of America.

Cohen, who chairs Our Revolution, the political organization of Vermont Independent Senator Bernie Sanders, said Biden’s team has reason to closely follow the talks, but stepping up involvement might be counterproductive at this point.

“I’m not sure their intervention is welcome. If it’s not welcome, it’s not useful,” he said.

‘History of Militancy’

The Biden administration is encouraged that negotiations have resumed, and officials believe the situation does not present the same kind of immediate threat the freight-rail crisis did, which required the president and Congress to step in.

“These are collective-bargaining negotiations happening at the table as they appropriately should,” top White House economic adviser Brian Deese told reporters on Tuesday.

Biden has received regular updates on the talks and Cabinet officials — including Labor Secretary Marty Walsh and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg — have monitored the bargaining process and communicated with labor and management representatives, according to a senior administration official. Officials believe they are in a better position to prevent a full-blown dispute than they were with the freight-rail negotiation.

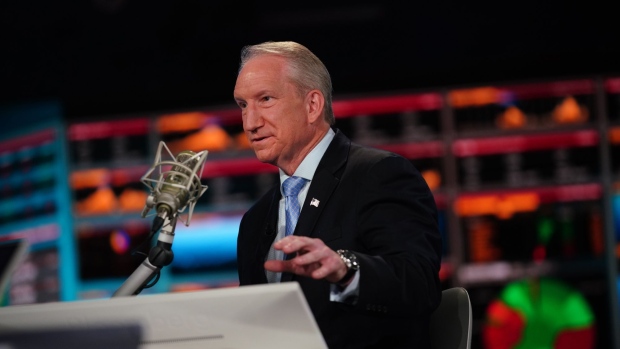

“Unfortunately for the rail unions, I did not get involved until they were 80% through negotiations, meaning they were not able to get deals done,” Walsh said on Bloomberg Television. “On the port negotiation, I have been in it from the beginning.”

A dispute over the assignment of work at a terminal in Seattle is among the reasons that contract negotiations have dragged on for months. Jurisdiction, wages, benefits and automation are key contention points in the talks.

The parties haven’t unveiled any progress since a tentative health-care deal was reached in July, and shippers are finding themselves diverting cargo to other parts of the country as anxiety builds. Flashbacks of the last contract negotiation, which began in 2014 and only ended nine months later when the Obama administration got involved, are contributing to the trend.

The Los Angeles-Long Beach port complex in Southern California has lost cargo in recent months in part due to the uncertainty around the dockworker talks. Volumes moved by Port of Los Angeles — traditionally the nation’s busiest — have declined for three straight months and plummeted 25% in October from a year earlier.

“Our members are most afraid of any disruption that happens as a result of these ongoing negotiations. They want certainty. The fact that this isn’t happening right now doesn’t make them feel better. They want a new contract in place,” said John Drake, vice president of transportation, infrastructure and supply chain policy at the US Chamber of Commerce.

If sufficient progress isn’t being made in the contract talks, the ILWU could cause significant disruption on the West Coast just by hewing more strictly to rules governing areas like safety, slowing down output, Cohen said.

“This is a union with a long history of militancy,” said Cohen.

The ILWU did not respond to requests for comment, while the PMA declined to provide one.

Biden Leverage

A slowing economy leading to a drop in imports could play into Biden’s hand. Maritime-area employers until just recently have enjoyed strong profits. But the sharp drop in volumes to West Coast ports could work as a bargaining chip in their favor, and against longshoremen.

As West Coast container volumes have fallen, the East Coast has handled more business, according to the National Retail Federation. The Port of New York and New Jersey, which for the past few months has held the crown as the country’s busiest, attributes at least 85% of its growth this year to diversion trends from the Pacific Coast.

During the 2014 dispute, President Barack Obama sent his secretaries of Labor and Commerce to mediate and Biden could use the same tactic if the situation reaches a breaking point.

Biden spoke about the union’s leverage during a December 2019 ILWU board meeting, saying, “if every piece of cargo in the back of a ship stopped dead in the water, the world would come close to an end.”

“Not a joke. You have enormous power,” Biden concluded.

--With assistance from Josh Eidelson, Jenny Leonard, Sarah McGregor and Brendan Murray.

(Adds White House comment in 11th paragraph)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.