May 20, 2022

Biden Struggles to Woo Asian Nations Wary of Upsetting China

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Joe Biden talked at length as a presidential candidate about the need to focus on China’s rising global power. Yet 17 months after taking office, Asian leaders are still waiting for details on a strategy for more US economic engagement in the region.

Before Biden touched down in South Korea on Friday, many officials in the region have struggled to understand the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework -- the main policy initiative he plans to unveil on the five-day trip. The US ambassador to Japan, Rahm Emanuel, said this week that some governments were asking “What is it we’re signing up to?”

While much of the framework remains vague, one thing is clear: It won’t provide lower tariffs to the US market, which is one of the main carrots for many nations to agree to higher labor and environmental standards that American lawmakers want in any pact. That’s particularly the case if they risk upsetting China by joining a framework seen as countering Beijing.

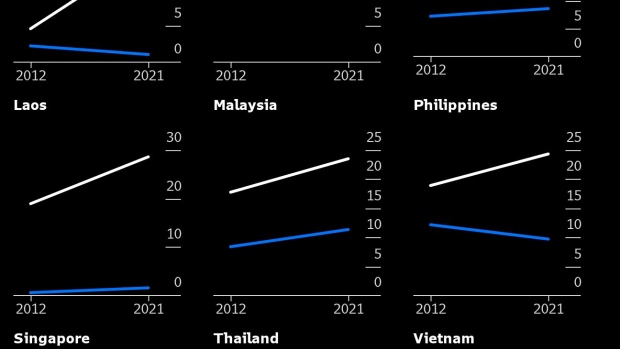

“All of the governments in Asia have China as their number one or number two importer and exporter, so how much do I want to potentially antagonize my biggest economic partner in exchange for unclear, if any, benefits from the US?” said Deborah Elms, Singapore-based executive director of the Asian Trade Centre. “What it looks like is a lot of conditions and not a lot of economic benefits for participants.”

For Biden, the problem is largely domestic politics. The administration knows the US must engage more with Asia to counter China’s growing economic power, but it also doesn’t want to spend political capital making the case for rejoining the 11-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, a regional trade deal that Donald Trump withdrew from in 2017.

Already plagued by low approval ratings, the president’s ability to tackle soaring prices for gas, food and other every day items -- as well as a baby formula shortage -- could determine whether his fellow Democrats hang on to their slim House and Senate majorities in midterm elections six months from now.

So instead the US is trying to come up with something that looks like a big trade deal without risking any domestic blowback. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan described the economic framework as “not a traditional free trade agreement,” while saying it would deal with supply chains, the digital economy, clean energy and investments in infrastructure.

Details so far are hazy. The Financial Times reported Friday that the US had diluted the language in the document in a last-minute move to attract more countries to sign up. An earlier draft had said the nations would “launch negotiations,” the paper said, citing people familiar with the situation and an earlier draft.

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Singapore, which relies on strong open trade, has been an advocate of more US economic engagement in the region even as it has said it was a mistake to pull out of the TPP, now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“I would say you could make this as substantive as possible,” Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in March. “Let us take some baby steps towards market access and trade liberalization.”

Lawrence Wong, who is set to take over from Lee, also said the US framework should be open to China to “build shared interdependencies” and “ensure a path away from a conflict down the road.” Indonesia President Joko Widodo this month also said the initiative “surely must be inclusive.”

Still, the US is no longer having substantive talks with China on trade, even though Sullivan said this week that Biden was set to soon speak again with Chinese leader Xi Jinping. In March, U.S. trade chief Katherine Tai said discussions with China have been “unduly difficult” and said it was time to focus on boosting American competitiveness and working with allies to make supply chains more resilient.

On Friday, Biden visited a Samsung Electronics Co. semiconductor complex in South Korea with newly elected President Yoon Suk Yeol, who said he’d seek to upgrade US-South Korea relations “into an economic-security alliance.”

The US global share of the market has declined to only 12%, and there is room for Taiwan and South Korean manufacturers to step in, said Thomas Byrne, president of The Korea Society.

“The sleeping elephant is semiconductor supply chain resiliency and restoring fab manufacturing in the U.S.,” he said. He also said the administration should “work harder -- wake up? -- with the reconciliation process in Congress” to pass legislation that would free up billions of dollars to boost chipmaking in the US.

In Asia, countries also want to see signs of US staying power in the wake of its withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, said Bill Hagerty, a former American Ambassador to Japan. China has regularly flown military jets toward Taiwan, and asserted its territorial claims in boundary disputes with India, the Philippines and Japan.

“What they are looking for is evidence of America’s resolve,” Hagerty said. “There’s also great concern that America’s attention might be taken away from their region because of what’s happening in Ukraine.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.