Feb 13, 2022

Biotech Money Shock: Investors Unwind Speculative Bets as Pandemic Fears Fade

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The first year of the Covid-19 pandemic fueled a frenzy for biotechnology stocks. Now, with vaccines in millions of arms and the omicron variant on the wane, there are signs investors are ready to move on.

After cresting at nearly $5 billion a month in early 2020, inflows into health-care funds have slowed to a more modest $800 million a month, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence. While that suggests that a healthy appetite for the shares of vaccine makers and other drug companies remains, the excitement — and fear — stoked by the early days of the pandemic has subsided.

What's more, those who embraced the shares of riskier drugmakers have taken their lumps of late.

The Nasdaq Biotechnology Index, the most widely watched gauge of the sector's performance, has fallen 25% since hitting a 52-week high on Aug. 9. The SPDR S&P Biotech, or XBI, an exchange-traded fund that specialists use to track the industry’s performance, has plummeted 44% over the past year. Over the same span, the broader market has been climbing, with the S&P 500 up 13%.

Holding risky and oftentimes slow-developing biotech companies suddenly seems less exciting, less promising, and far more unnerving, especially with the prospect of rising interest rates.

“The market last year was fairly crazy, to be honest, because it was really overheated,” said Ipsen SA Chief Executive Officer David Loew. “We observed that some of the companies were able to raise money on projects where we looked at them and we said, ‘This doesn't make sense.’”

For biotech investors in for the long haul, the landscape is starting to take on a more recognizable configuration. The current level of inflows suggests the industry is far from collapsing. More likely, these investors say, is that it is following its long-established pattern of fast growth followed by abrubt contractions, shaking out some of the pandemic hype but sparing and possibly strengthening companies with solid science and deep pockets.

“A year ago, companies were being valued as exciting ideas,” said Brad Loncar, chief executive officer of Loncar Investments. “When the market corrects like it has, I think we’re going back to valuing them as businesses.”

That means the smart money isn’t abandoning the sector, said Piper Sandler analyst Chris Raymond, who analyzes biotech money flows. But those who remain are taking a harder look at the companies they’re willing to back. Some are shying away from companies that are years away from producing data that proves their ideas could translate into medicine.With interest rates and inflation on the upswing, investors generally prefer later-stage assets that have proven to be less risky than ideas many are willing to bet on during boom times, according to Brian Coleman, global head of capital markets at Locust Walk, an investment bank and advisory firm specializing in life sciences. There’s still plenty of appetite for companies based on early ideas and scientific advances, he said, but in the current economic climate they tend to thrive more in privately financed firms flush with cash. Health-care venture firms raised $28.3 billion in 2021, compared to $3.7 billion in 2011, according to Silicon Valley Bank.

“The bar is always pretty high but it’s higher in uncertain times,” Coleman said.

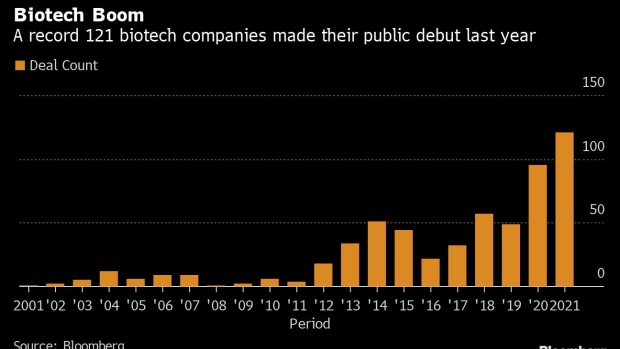

A record 121 biotech companies went public in 2021, topping the record 95 set only the year before, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. With investors hungry to break into the space, even companies that were years away from testing their ideas in humans enjoyed a welcome reception.

Many early-stage companies are now watching their stocks fall precipitously because they were priced unjustifiably high, said Stelios Papadopoulos, chairman of Biogen Inc. and a former investment banker.

“The problem is not too many science experiments,” said Papadopoulos, who has tracked biotech IPOs since 1979. “The problem is too many highly priced science experiments with a very significant amount of risk associated with them.”

People searching for what they hope will be “the next Moderna” may be sorely disappointed. After a long and tortured development history and billions of dollars in investments, Moderna Inc.’s first product was its Covid-19 vaccine. Still the perception persists that Moderna was an overnight hit, even though the backstory involved “10 years of homework ,” said Christiana Bardon, who leads public market investing at MPM Capital, a biotech-focused private-equity firm.

Broader market factors are hitting biotech especially hard. After years of near-zero interest rates, even small upticks can make it too expensive to fund companies that are many years away from an approved product, said Patrick Nosker, director of research at Affinity Asset Advisors LLC.“The rug was pulled out from underneath a lot of these companies that went public that may not have a drug on the market maybe even before 2030,” Nosker said.

People also tend to assume higher growth stocks, including biotech, perform worse in inflationary environments. But that’s not what the data show, said Raymond, the Piper Sandler analyst. Those macro trends give biotech investors and analysts hope that this downturn, like those before it, will pass.

Experienced investors and analysts say they’ve lived through plenty of painful periods before. Bardon and MPM co-founder Ansbert Gadicke compare the experience to hibernating bears: The companies that are well prepared will survive to see the spring and the older bears, the experienced investors, who have experienced winters before know that this one will eventually end as well.

“If you’re a good company with good science with a good business model, you’ll make it through,” said Brad Loncar, the Loncar Investments chief executive. “If you’re just based off a PowerPoint deck that’s hopes and dreams, you might be in some trouble.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.