Jul 28, 2021

Boeing advances on first profit since 2019 as troubles ease

, Bloomberg News

Boeing 777 engine failure prompts groundings in U.S., Asia

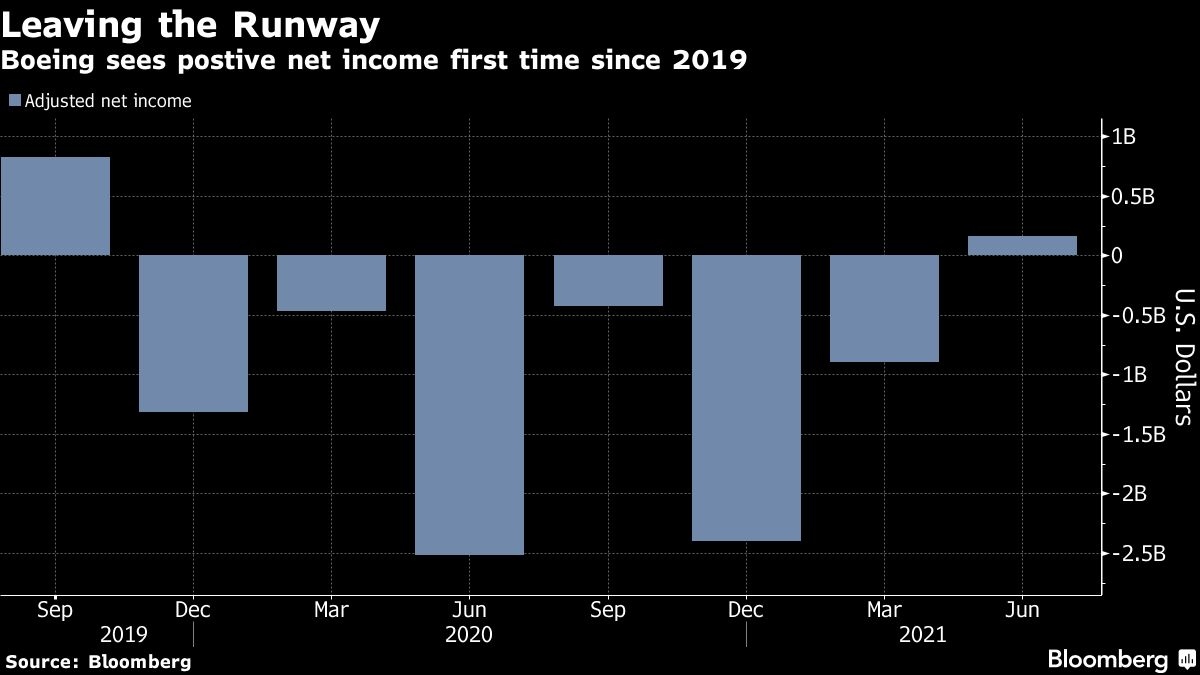

Boeing Co. earned a profit for the first time in nearly two years, surprising Wall Street and hinting at a budding turnaround after one of the worst financial crises in the planemaker’s century-long history. The shares jumped.

Adjusted earnings of 40 cents a share weren’t the only sign of progress in the company’s second-quarter financial results. In addition, the manufacturer burned through just US$705 million in cash, better than the US$2.76 billion outflow that analysts had predicted.

Wednesday’s results suggest that Boeing is starting to emerge from a deep slump caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the company’s own quality lapses, which were tied to two deadly crashes of its best-selling 737 Max plane. With its business stabilizing, Boeing has halted large-scale job cuts well short of earlier plans to eliminate nearly 20 per cent of its payroll as it gears up for a production increase over the next few years.

“We are turning a corner and the recovery is gaining momentum,”Chief Executive Officer Dave Calhoun said on an earnings call. “I’ve said before that we view this year as a critical inflection point, and it’s providing to be just that.”

Boeing jumped 4.5 per cent to US$232.20 at 1:49 p.m. in New York after advancing as much as 6.8 per cent, the biggest intraday gain in four months. The shares had climbed 3.8 per cent this year through Tuesday, trailing the 15 per cent gain for the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

The company plans to hold employment steady at 140,000 jobs, representing a 13 per cent reduction from pre-COVID levels, as its finances recover. The surprise second-quarter profit compared with an average loss of 81 cents expected by analysts surveyed by Bloomberg. Revenue rose 44 per cent to US$17 billion. Analysts had predicted US$16.5 billion.

“Today could be seen as a tactical victory for Boeing, but the strategic challenges remain,” said Robert Stallard, an analyst at Vertical Research Partners.

Indeed, the Chicago-based company faces a long road ahead. The Max is still banned from the skies in China, its biggest foreign market, eight months after U.S. regulators allowed flights to resume. Boeing is also wrestling with manufacturing flaws that have halted deliveries of its 787 Dreamliner, another key source of cash.

Meanwhile, Boeing faces a powerful rival in Airbus SE, which is looking to capitalize on its larger order backlog. The European planemaker is slated to report its results on Thursday.

China, Dreamliner

But Boeing is advancing on key fronts, Calhoun said. The company is making progress in discussions with regulators in China and expects the 737 Max grounding to be lifted there and in other hold-out nations this year, he said.

The company has largely resolved technical issues raised by China’s aviation authority, Calhoun said. And while the U.S. and China are deadlocked on trade talks, they don’t need a bilateral agreement for mutually beneficial areas such as Max deals. Boeing is counting on Chinese orders to help fill its production schedule, while the country’s airlines need the Max to handle an influx of travelers with next year’s Winter Olympics.

As for the Dreamliner, the company has temporarily slowed output of the marquee wide-bodies as it searches for and repairs structural imperfections that are about the width of a coat of paint. While the mushrooming inspections grabbed headlines, Boeing has used the COVID-induced lull in long-range travel to address other shortfalls in its factory and supply-chain.

The company is addressing nagging issues with 787 production now, in anticipation that output will start to pick up in the second half of 2022 as borders reopen, Calhoun said.

“When we get to that moment, we have to be perfect,” the Boeing chief told CNBC earlier Wednesday.

The balance of deferred production costs still on Boeing’s books from the Dreamliner’s troubled start rose by US$124 million in the second quarter to US$14.9 billion, reversing years of declines.

But the company didn’t take the steep accounting charges that some analysts had predicted after executives had warned that cutting production below a pace of five jets a month could clip margins and force the 787 program into a reach-forward loss.

Still, Calhoun and Stan Deal, Boeing’s Commercial Airplanes chief, face a difficult juggling act as they try to get production running smoothly without adding to the stockpile of hundreds of undelivered planes, mostly wide-body 787 jets and narrow-body Max aircraft.

The jetliner division pared its operating loss to US$472 million from a deficit of US$2.76 billion a year earlier, when the company wrestled with the worst of the COVID-19 crisis. Commercial revenue more than doubled to US$6.02 billion as deliveries rose.

Boeing is now manufacturing sixteen 737 Max jets a month and still plans to increase output to 31 a month by early next year. Inventories for the division declined by about US$330 million to US$70.7 billion during the quarter.

But the cash that would typically be generated by the Max has been depressed by low production volumes since U.S. regulators cleared the plane’s return last year after a 20-month grounding.

Boeing isn’t netting much cash by clearing its inventory of the aircraft, either. Airlines are mostly using credits, both for advances already paid to the planemaker and compensation for the grounding, Agency Partners analysts Nick Cunningham and Sash Tusa said in a Tuesday report.

Bloomberg Intelligence analyst George Ferguson expects Boeing’s revenue to be affected in the near-term by a spate of 737 Max deliveries to Southwest Airlines Co., which used credits to lower its cash payments. So even with the jetliner business gaining steam, Boeing will have to continue relying for a while on its defense and services businesses.

“The big picture is: Defense, global services make up for commercial,” Ferguson said.