Mar 13, 2019

Boeing crash isolates FAA as China leads push against 737 Max

Bloomberg News

The second fatal crash of a Boeing Co. (BA.N) 737 Max aircraft in less than five months is creating a new hierarchy in aviation safety. Thrusting to the top: China.

Three days after an Ethiopian Airlines jet crashed, killing all 157 people on board, country after country ignored assessments by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration that the plane is safe to fly. Canada agreed it was too early to act but many fell into line in growing numbers behind the first major nation to ground its 737 Max fleet -- China.

In doing so, long-time American allies including the U.K. and Australia broke convention by snubbing an authority that has defined what’s airworthy -- and what’s not -- for decades. New Zealand, the United Arab Emirates and Vietnam on Wednesday became the latest countries to block the 737 Max, helping legitimize China’s early verdict on March 11 that the plane could be unsafe.

"The FAA’s credibility is being tested," said Chad Ohlandt, a Rand Corp. senior engineer in Washington. "The Chinese want their regulatory agency to be considered a similar gold standard.”

One day after the Ethiopian Airlines flight plunged to the ground, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) drew a possible connection between the crash and Lion Air’s in October. A preliminary report into the earlier disaster, which killed 189 passengers and crew, indicated pilots struggled to maintain control following an equipment malfunction. Both flights, on almost brand new planes, ended minutes after takeoff.

Ethiopian Airlines CEO Tewolde GebreMariam told CNN that the latest crash and the Lion Air tragedy had substantial similarities. Separately, the Wall Street Journal reported that Ethiopia wanted to send the flight-data and cockpit-voice recorders to the U.K., causing U.S. investigators to hold intense behind-the-scenes talks to bring the parts to America.

Meanwhile, the CAAC asked domestic airlines to ground their 737 Max 8 fleets. "There needs to be reason for us to change that decision," said CAAC’s deputy head Li Jian. Domestic carriers including China Southern Airlines Co. and Air China Ltd. account for about 20 per cent of 737 Max deliveries worldwide through January, according to Boeing’s website.

To be sure, Chinese aviation regulators do tend to be conservative. They banned the use of cellphones on aircraft until 2018, years after regulators in developed countries gave them the green light.

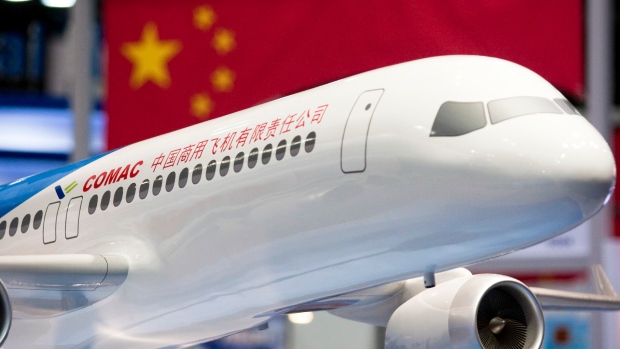

But China is gaining influence. As an air travel market, it’s on track to surpass the U.S. as the world’s biggest around 2022. It’s also seeking some degree of self-sufficiency through its national champion: Commercial Aircraft Corp. of China Ltd., which is known as Comac.

As a regulator, recent events indicate China is on its way to attaining the level of authority enjoyed by the FAA and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, giving the country global recognition for its ability to determine when an aircraft is safe to fly.

In a deal signed between CAAC and FAA in 2017, aviation regulators from China and U.S. agreed to recognize each other’s airworthiness standards, paving the way for Chinese-made aircraft to win FAA certifications to sell in the global market. A similar deal is also being finalized with their European counterpart.

China’s first homemade commercial aircraft C919, which state-owned Comac has developed to break the duopoly held by Airbus SE’s A320 and Boeing’s 737 in the narrow-body market, is trying to get airworthiness certification from both CAAC and EASA.