Nov 18, 2020

Boeing's 737 Max is coming back. Ready to board?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Boeing Co.’s 737 Max is back. Is the world ready for it?

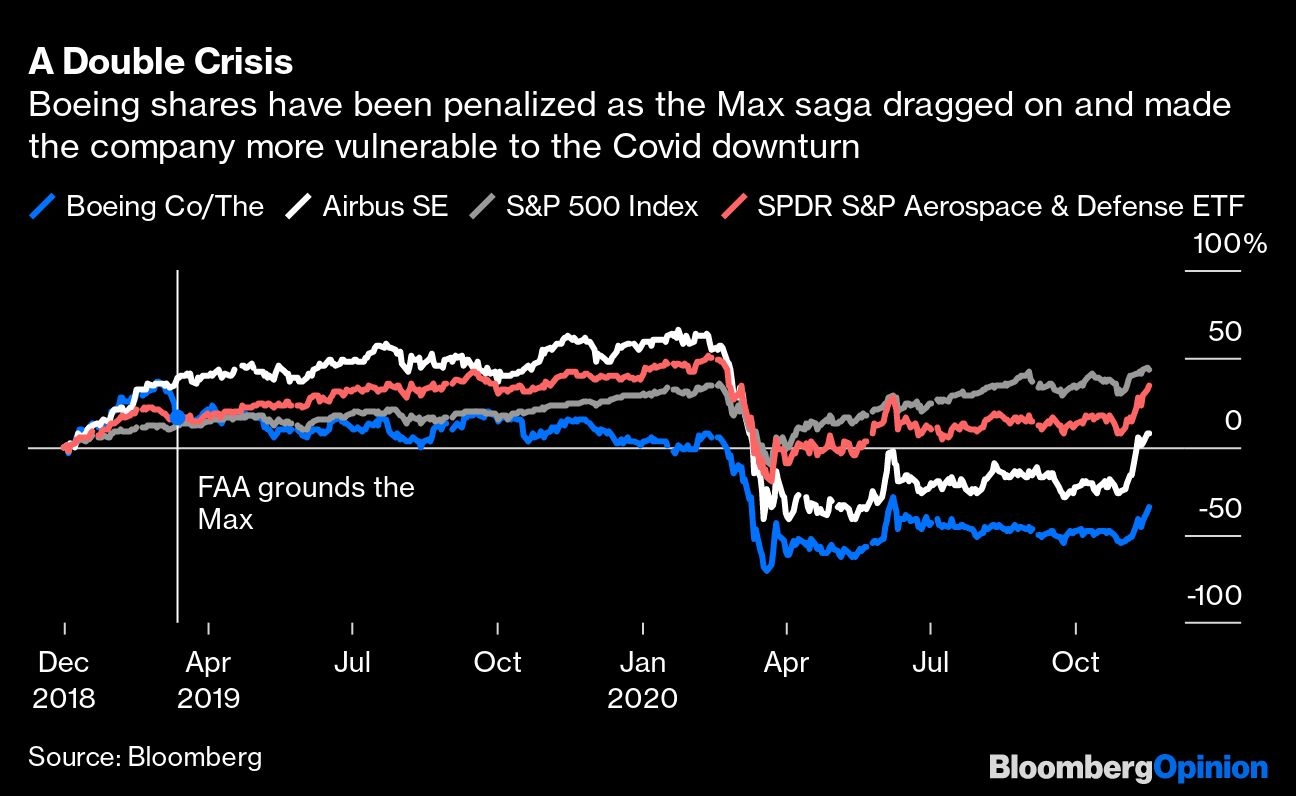

The Federal Aviation Administration is expected to finally approve the Max to resume commercial flights on Wednesday, about 20 months after a pair of fatal crashes forced regulators around the globe to ground the once top-selling jet. European regulators are expected to follow suit in coming weeks. This is a major milestone for Boeing and a turning point for a company that somehow repeatedly managed to make an already devastating crisis worse for itself — remember the overly ambitious timelines for the Max’s return? Financially, securing the FAA’s blessing will allow the company to finally make money off the roughly 450 Max jets it has built but not yet delivered because of the grounding order. These days, though, getting regulators’ approval is only half the battle for Boeing.

The company is also contending with a global pandemic that’s made airlines more prone to cut back their orders than to take new planes. Nearly a quarter of the 450 Max jets in storage are “white tails” — planes whose original buyers have backed out, so their tails are unmarked by airline logos — Bloomberg News reported. In total, more than 1,000 Max jet orders have either been canceled this year or deemed doubtful under accounting rules.

For those airlines that already have Max jets, there will be a lag before the planes actually ferry passengers. Many have been parked in the desert and need to be brought back into flying condition. The airlines also have to implement the FAA’s required upgrades and retrain pilots. The Max’s biggest operator, Southwest Airlines Co., has said it expects this process to take three to four months and isn’t planning on using the jet for passenger flights until at least the second quarter of 2021. Your first chance may come with American Airlines Group Inc., which has said it will fly the Max on a Miami-New York route starting on Dec. 29. What better way to close out 2020.

The natural question, after the longest grounding of an aircraft in modern U.S. history, is whether the plane is safe. The answer is yes, in part because this has been the longest grounding and also because the FAA’s proposed fixes go beyond the specifics of the software that was blamed for the catastrophes. This software — called the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) — was originally added to the Max to guard against an aerodynamic stall, but it instead repeatedly forced the planes to nosedive and set off a cacophony of alerts that overwhelmed the pilots. Boeing will now make the system dependent on two sensors, rather than just one, to avoid erroneous readings. MCAS also will only activate once, reducing the amount of power the system can exert on the nose of the plane. (1) The FAA has also backed a broader overhaul of the plane’s computers to improve reliability and separate bundles of electrical wiring that had the potential to short circuit.

Whatever the risks were around this airplane, it seems likely that the FAA has found and evaluated them at this point. Why the agency didn’t do this in the first place is a different question that features prominently in a congressional push for reforms to the FAA’s relationship with the companies it oversees. The House of Representatives on Tuesday passed bipartisan legislation that requires an independent expert panel to review Boeing’s safety culture; extends whistleblower protections to manufacturing employees; and gives the FAA more oversight over company workers who conduct delegated certification work, among other things. A similar bill is being considered by the Senate’s Commerce Committee. Boeing has already indicated that the approval process for its 777X widebody jet is taking longer than it had previously expected amid the heightened scrutiny and the pandemic.

Perhaps the most consequential change from a symbolic standpoint is the expected requirement that pilots undergo simulator training before flying the Max again. One reason Boeing decided to build the Max variant of its 737 model in the first place rather than start from scratch with a new design was that it wanted to keep training costs down for airline customers. The goal was to avoid putting itself at a competitive disadvantage relative to rival Airbus SE’s models, which lent themselves more easily to upgrades with larger, more fuel-efficient engines. Boeing can no longer make the same sales pitch on training costs and it’s now fallen behind its European rival anyway.

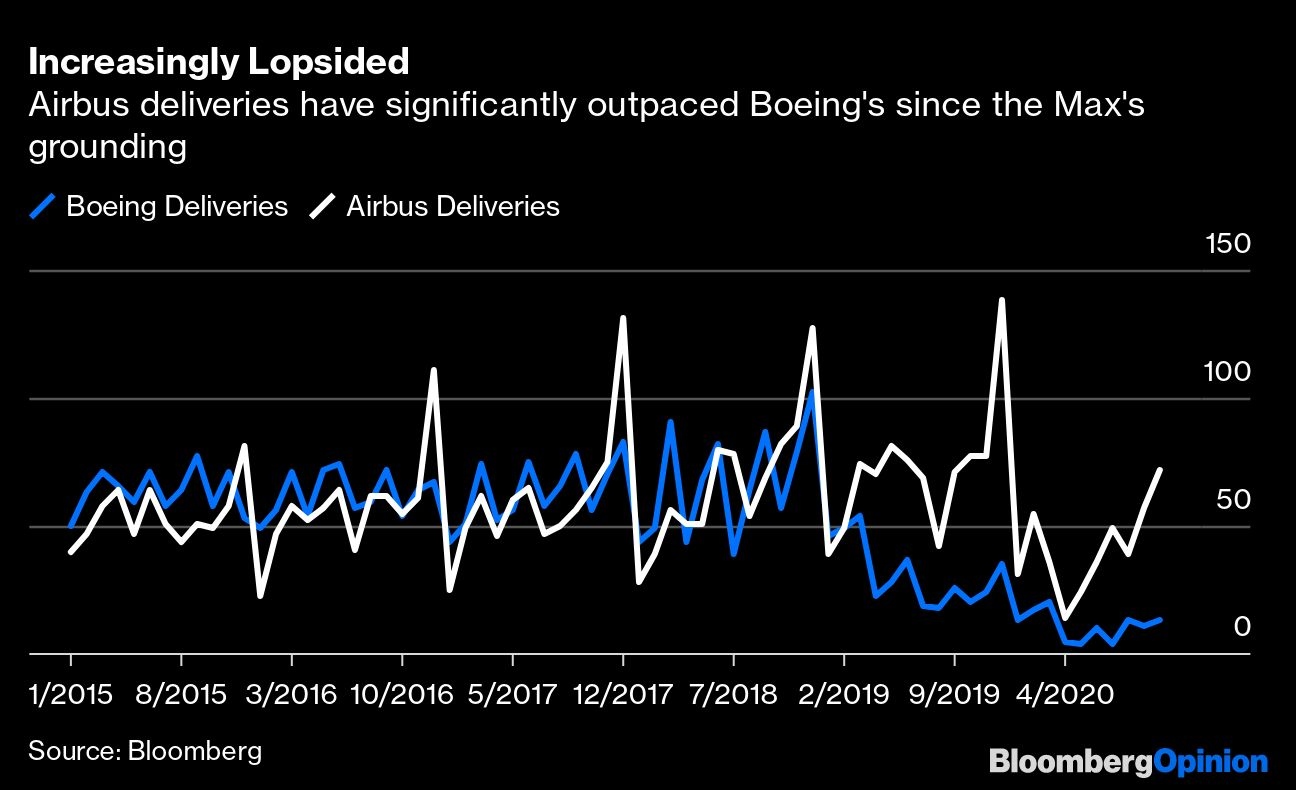

Airbus certainly hasn’t been immune to the fallout from the global pandemic but the fact that its planes haven’t been grounded for more than a year has made it comparatively harder for airlines to abandon their orders. In fact, Airbus has told its suppliers to be ready to ramp up production on its A320neo family of jets to 47 a month by the second half of 2021, compared to 40 currently. The company had 11 new orders in October across its portfolio, compared to zero at Boeing. The narrow-body jet market is expected to recover faster from the pandemic because the planes tend to be used on shorter-haul flights. As of the end of the third quarter, Airbus had a commanding 64 per cent share of that market, according to Vertical Research Partners analyst Rob Stallard.

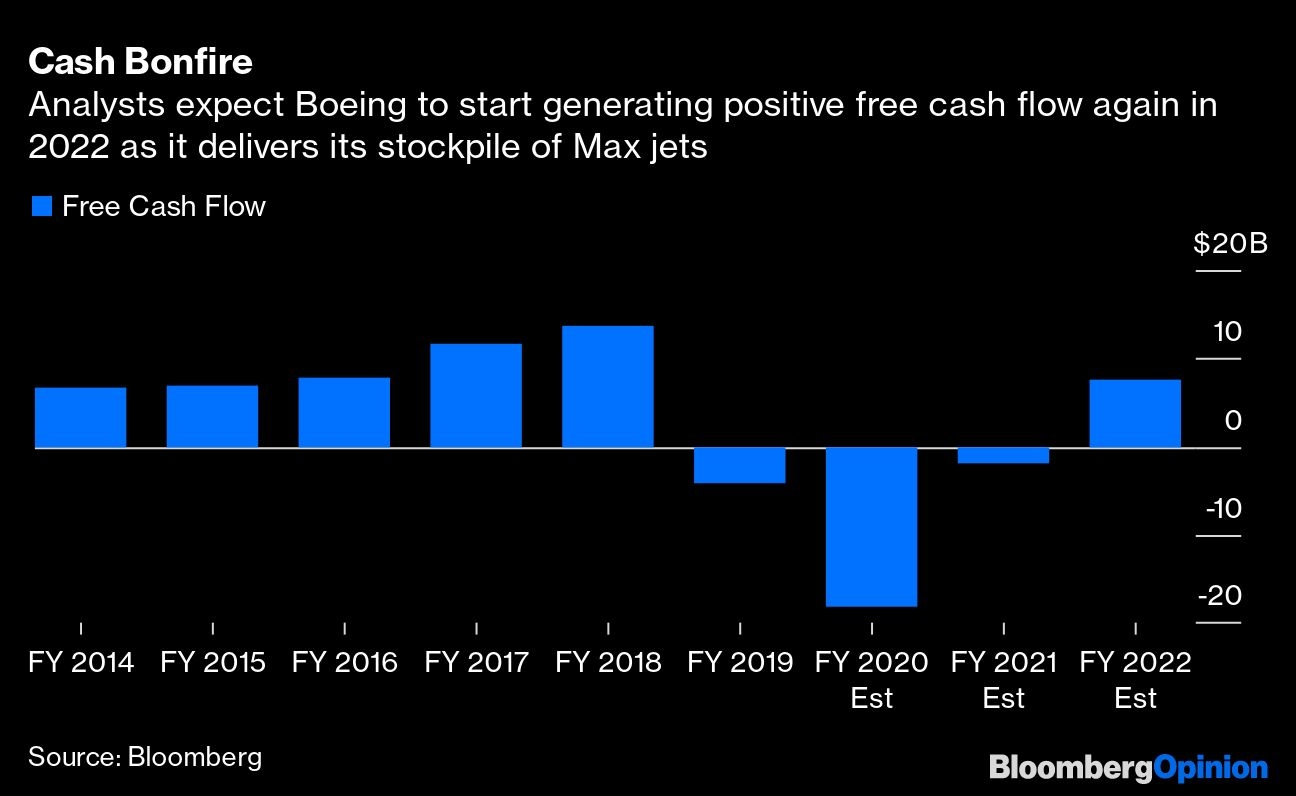

It’s not clear how Boeing rectifies this problem. Reuters reports that the Max brand name may be phased out over time, but what the company really needs is a new jet that's better than anything Airbus has on offer. The Wall Street Journal has reported that Boeing is gauging interest in a new commercial aircraft that would bridge the gap between the Max and the company’s larger 787 Dreamliner. But Airbus is already selling longer-range versions of its A320 model that fill this niche to some extent. It's unlikely that the technology exists yet to make significant enough improvements on Airbus's designs; that may require advancements in hybrid or electric engines, which could take decades to come to fruition. But all of this is moot until Boeing starts bringing in cash again. It’s burned through more than $15 billion so far this year and had $61 billion of debt at the end of the third quarter.

The key to addressing this cash crunch is delivering those 450 parked Max jets; that won’t be easy. Recent positive news on COVID-19 vaccines may signal a more optimistic path for an air travel recovery than the 2023 or 2024 time frame outlined by most members of the sector. But the best-case scenarios have a vaccine becoming widely available in the spring, still months away, and some travel — particularly lucrative business trips — may never return.

It doesn’t help that the plane has gotten more expensive for European buyers; the European Union this month moved to apply a 15 per cent tariff to U.S.-made planes as part of a broader retaliation in a long-running spat with America over illegal aircraft subsidies. Ireland-based Ryanair Holdings Plc has said it won’t pay tariffs on Boeing jets. This suggests that absent an intervention and resolution of the standoff by U.S. President-elect Joe Biden, Boeing would have to step in and shoulder the extra cost. (2)

So good luck to Boeing and the Max. They’re going to need it.

(1) The European Union Aviation Safety Agency has said it will go a step further than the FAA and also require Boeing to develop a suite of virtual sensors that can act as a backup to the traditional angle-of-attack vanes whose erroneous readings triggered a nosedive in the Max crashes. But given the complexity of developing this synthetic air-data system, the regulator has signaled it won’t hold up the recertification of the Max over this issue. Instead, itmay issue its own airworthiness blessing this month, with the expectation that Boeing will make the additional upgrades over the next two years.

(2) Airbus has avoided corresponding U.S. tariffs on certain A320 and A220 models by building jets for U.S. customers at a plant inAlabama.Delta Air Lines Inc. found a loophole by basing European-built jets overseas and using them for international travel.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.