Oct 7, 2021

Boris vs Business: Five Charts Show U.K. Economic Reality

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Boris Johnson’s optimistic vision for the post-Brexit economy in the U.K. is being challenged by big business and some traditional supporters of the ruling Conservative Party.

The prime minister says Britain is seeing a surge in wages and will no longer rely on mass immigration. That, in turn, he hopes will reverse the malaise the U.K. has suffered for years as a slow-growth, low productivity economy.

While his remarks this week drew adulation from the Tory faithful, they landed poorly outside the hall where worker shortages left consumers and businesses struggling to get essential supplies.

“Economically illiterate” was the conclusion of the Adam Smith Institute, a research group usually sympathetic to Conservative free-market policies. The Confederation of British Industry warned of the risks of putting ambition above action.

Here’s a quick appraisal of some of Johnson’s economic arguments:

Wage Growth

“After years of stagnation –- more than a decade -- wages are going up faster than before the pandemic,” Johnson said in a speech to the Conservative Party annual conference on Wednesday.

While Johnson is correct to say that wage growth is picking up, that’s largely due to labor shortages created by the pandemic. If companies are unable to absorb higher wage bills or increase their productivity, the result will be higher prices for everyone. It also ignores the fact that inflation is running at 3.2% and forecast to exceed 4% by the end of the year. That would in effect eat up the wage increase.

Immigration

“We are embarking now on a change of direction that has been long overdue in the U.K. economy. We are not going back to the same old broken model with low wages low growth low skills and low productivity, all of it enabled and assisted by uncontrolled immigration,” Johnson said in his conference speech.

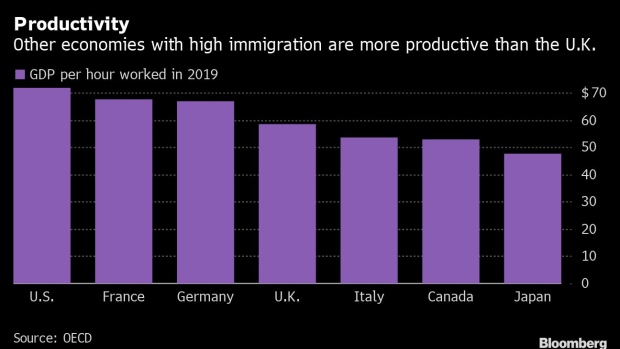

The prime minister is right to flag the U.K.’s stagnant productivity as a problem, but immigration may not be the cause. Countries such as Germany and France also have high immigration levels but have more productive economies. That suggests that it’s possible to boost productivity while still allowing low-skilled migrants into the country.

Investment

“We will make this country an even more attractive destination for foreign direct investment,” Johnson said. “We are already the number one.”

It’s true that the U.K. has historically led on FDI inflows in Europe, but its position is slipping. Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development show that in fact Germany was the number one destination for foreign direct investment in 2019, the last year before the pandemic, after trailing the U.K. for the previous five years.

Johnson also argued that firms have relied too much on a plentiful supply of foreign workers rather than investing in productivity-enhancing technology and equipment. But prior to the Brexit referendum in 2016, overall business investment was in fact growing at more than 5% a year. It’s largely flat-lined since.

Johnson is correct to identify productivity as the economy’s main underlying weakness. On the eve of the pandemic, output per hour was only 5% higher than it was when the financial crisis struck 12 years earlier. Low productivity hampers the ability of firms to increase wages and limits how quickly the economy can grow without triggering faster inflation.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.