Jun 1, 2023

Brazil’s Economic Growth Bounces Back Under Lula and Defies High Interest Rates

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s economy roared back in the first months of 2023, lifted by bumper harvests that outweighed the drag of double-digit borrowing costs.

Official data released on Thursday showed gross domestic product expanded 1.9% in the January-March period from the previous quarter, much more than the 1.2% median estimate of analysts surveyed by Bloomberg. From a year ago, the economy grew 4%.

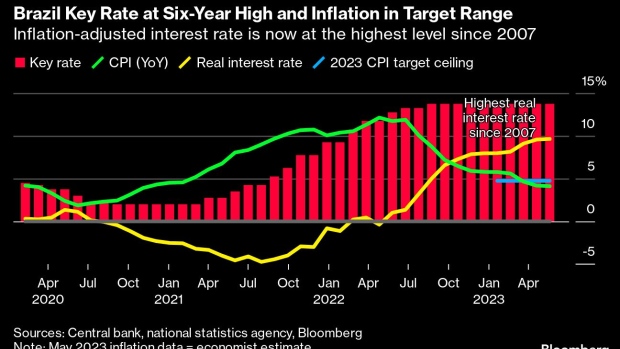

A rebound in Brazil’s agriculture and a strong labor market helped deliver far better results than economists had forecast at the start of 2023, though few see it lasting. The highest interest rates in six years are weighing on business and consumer confidence — and have President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva clamoring for drastic changes in monetary policy.

“Looking ahead, if we stop having the effect from agriculture and we expect that monetary policy remains contractionary, GDP should turn negative in the second half” of the year, said economist Gustavo Arruda, head of Latin America research at BNP Paribas.

An agricultural powerhouse, Brazil is the world’s top exporter of goods including beef and soybeans. After being hit by adverse weather in recent years, the country saw its biggest ever soybean harvest for the 2022-2023 season, while crops like coffee and corn are expected to hit records.

The agricultural sector surged 21.6% and services advanced 0.6%, representing the main drivers of quarterly growth. Meanwhile industry fell 0.1%, the statistics agency said.

Caution

Three years since the coronavirus crashed the world’s economy, Brazil is proving resilient. Real activity is now 6.4% above pre-pandemic levels but worries abound about growth fizzling.

What Bloomberg Economics Says

“Brazilian growth impressed in the first quarter, led by a surge in agriculture and livestock, but the breakdown warrants caution on the outlook. With agriculture boost fading, we expect growth to slow significantly over the rest of the year.”

— Adriana Dupita, Brazil and Argentina economist

— Click here to read the full report

A similar story is playing out across the region as the weight of high borrowing costs saps momentum from Latin America’s top economies.

The GDP reading is the first since Lula, as the 77-year-old leftist is known, took office for his third term. He has staked his presidency on fighting hunger and bringing back the glory Latin America’s biggest economy enjoyed when he led Brazil during the commodities bonanza of the 2000s. More than a few political observers doubt the he’ll take comfort from the positive print.

“Lula will claim that the results could have been even better if interest rates were lower,” said Mario Braga, a Sao Paulo-based political analyst for the consulting firm Control Risks.

Read more: Lula Lashes Out and Sends Warning to Central Bankers Everywhere

Since returning to power in January, Lula has clashed regularly with central bank President Roberto Campos Neto and cast current levels of borrowing costs — the benchmark Selic stands at 13.75% — as the country’s main obstacle to growth.

2% Growth

Following the data release, Brazil’s Planning and Budget Minister Simone Tebet told journalists in Brasilia that the economy could expand more than 2% this year, and there was no reason why interest rates shouldn’t start falling. Credit Suisse revised up its year-end GDP growth forecast to 2.1%, while Capital Economics lifted theirs to 2.3%.

But the monetary authority, which is autonomous from the executive branch, has brushed off Lula’s demands and offered no indications about possible easing.

After fighting back a surge in inflation that followed the end of pandemic lockdowns, policymakers are concerned that prices will pick up again later this year. Annual inflation has eased from last year’s peak of over 12% to 4.07%, near the central bank’s targets of 3.25% for 2023 and 3% for 2024, but Campos Neto has called for “patience and serenity” amid the slowdown.

Brazilians seem tired of waiting. Credit card rates and household defaults are surging. And businesses big and small are struggling as financing has been put out of reach for many shoppers.

“Today we are in a very difficult situation in this sector, because today nobody buys a car anymore,” Ciro Possobom, president of Volkswagen AG in Brazil, said in an interview.

Read more: Lula Cuts Car Taxes to Revive Brazil’s Ailing Auto Sector

The government has tried to cushion the impact of high borrowing costs with measures such as tax breaks and cash relief for the poor. But Lula is struggling to navigate a divided congress, potentially putting his more ambitious legislation to overhaul the economy at risk.

Meanwhile, many Brazilians are still feeling the pinch. Selma Fuentes, 48, a single mother who manages supplies for a construction company in the city of Mogi das Cruzes in Sao Paulo state, says she’s cutting back on groceries like beef and sweets.

“Today it’s like a balancing act with money to manage the bills,” she said.

Solange Srour, chief economist for Brazil at Credit Suisse, says that the GDP data would ultimately serve to cement the central bank’s position, and that the economy would face higher rates for longer.

“A lot of people have set this resilience aside or want to see a glass more full than empty,” she said. “The truth is that when we celebrate that the economy is doing well, we have to be worried about inflation.”

--With assistance from Leonardo Lara, Giovanna Serafim, Guilherme Bento, Rafael Gayol and Tatiana Freitas.

(Updates with with year-end GDP revisions in 12th paragraph. A previous version corrected lanning and budget minister’s GDP forecast in 12th paragraph.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.