Aug 3, 2021

Brazil Set for Biggest Rate Hike Since 2003 as Economy Reopens

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

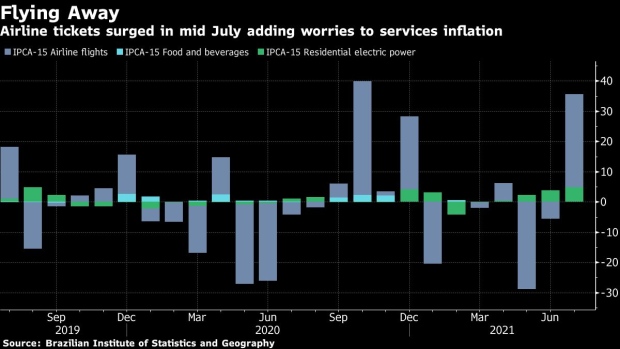

A new front is opening up in Brazil’s war against inflation amid surging costs for services from airline fares to appliance repairs, sparking speculation that one of the world’s most aggressive central banks may this week deliver its biggest interest rate hike in almost two decades.

Food and energy have been leading price increases in Brazil, with imports and other tradable goods close behind amid global supply-chain issues and a weaker currency. But now, with the Covid-19 vaccination rate slowly creeping up in a population eager to get back to restaurants, nightclubs and beach trips, services inflation is quickly accelerating: The annual rate is now more than double what it was less than a year ago.

Overall consumer-price increases are already running at more than twice the central bank’s target, leading economists to predict that policy makers will boost the Selic rate a full percentage point Wednesday to 5.25%, which would be the biggest increase since 2003.

The risk is that a surge in services inflation combined with the painful price increases already seen will require interest rate hikes so steep that the higher borrowing costs will sap economic growth.

“This is a dangerous moment,” Bruno Serra, the central bank’s monetary policy director, said at an online forum last month. “This is the most critical time for us to understand how the economy will react in the post-pandemic era.”

Brazil was already the most hawkish central bank in the region this year, with its 2.25 percentage points of interest-rate increases, second only to Angola worldwide. The median estimate of economists surveyed by the central bank is for the benchmark rate to end the year at 7%.

While faster inflation is a worldwide phenomenon a year-and-a-half into the pandemic, Brazil’s price increases began to take hold earlier than in most developed countries. It’s among the few nations in the world to have boosted interest rates to pre-pandemic levels, and economists say its struggles to mute inflation could be a sign of what’s to come in the rest of the world.

Accelerating Fast

For now, one measure of Brazil’s services inflation shows prices rose 2.3% in June. That’s still far below the overall inflation rate of 8.35%, but compares with services inflation of less than 1% in August 2020. That rapid acceleration is what’s worrying economists.

Only about one-fifth of the population is fully immunized, and yet the economy is almost fully reopened at this point. Airline fares surged 36% in the most recent data set from the statistics institute, while food outside home jumped 7.2%. Appliance repairs were 11% more expensive, while eyebrow waxes climbed a more modest 6.2%.

“We are seeing some segments of the services sector bouncing back faster than expected,” said Silvia Matos, an economist at the economic researcher Getulio Vargas Foundation.

Mobility isn’t back to pre-pandemic levels, but either out of exhaustion or boredom, Brazilians are taking their chances and traveling. After eight months of isolation, Joao Victor de Medeiros, a 28-year-old from the city of Natal who works at a startup, decided to go to the beach with his friends in early January. No one was vaccinated.

“Back then I was still very fearful, wearing masks everywhere, using tons of hand sanitizer,” he said in an interview. He’s loosened up since then, and is planning a trip to Sao Paulo a month from now.

The central bank began raising interest rates from a record low in March, increasing the benchmark by 0.75 percentage point three times. Both economists and traders are now signaling they expect a full percentage point increase on Wednesday, with more to come in upcoming meetings. That could drag on economic growth that analysts estimate will reach 5.3% this year.

Analysts surveyed by the central bank are optimistic that inflation will slow to 6.79% by December. But that’s still significantly above the bank’s 3.5% target, and pundits predict inflation will near 3.8% in 2022. Things could get worse if prices for services continue to climb at a fast clip.

“It’s a cause of concern,” said Daniel Karp, an economist at Banco Santander SA’s local unit. “Food, energy, gas -- they are all rising. Business owners can’t keep their margins so low anymore. So we have a spread of primary inflationary shocks.”

Services inflation could be particularly hard for the central bank to fight because some of the price increases are tied to higher wages. To Karp, the main problem with inflation now is not the pace, but its composition.

“Once services prices begin to accelerate, it’s pretty difficult to take them back where they were,” he said.

For now, economists predict that the central bank will leave rates unchanged in 2022 after raising the benchmark to 7% by the end of this year. But of course that could change if pressure builds in the services sector and neither food nor energy prices ease.

“The central bank has to monitor this because it could complicate the dis-inflationary story,” said Tony Volpon, who served on the central bank board from early 2015 to late 2016 and now works as an investment strategist for Wealth High Governance. “We really don’t know what the dynamic will be in Brazil. Models haven’t done great anywhere. We are flying blind.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.