Apr 11, 2021

Brexit Britain’s Biggest Test Might Be the Ability to Survive

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has a fondness for grand projects, but few are as eye-catching as the proposal for a physical link over the Irish Sea between Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Whether a multi-billion-pound pipe dream or a token of ambition befitting the post-Brexit era, a feasibility study is underway as part of the government’s review of how to better bind the United Kingdom and its four constituent nations. A more immediate concern may be whether the link could one day connect two independent states that are no longer part of the U.K.

As Britain marks 100 days since turning its back on the European Union, tussles have broken out with the continent over issues from customs checks to vaccination shots and financial services.

Tensions at home are raising the specter of a more existential conflict, however, one that will determine whether Johnson’s aim to strike out in the world under the banner of a reinvigorated “Global Britain” will need to be downgraded to a more humble “Global England.”

Scotland will hold elections on May 6 to its parliament in Edinburgh that are being cast as a vote on whether the nation has the right to—or the need for—another say on its constitutional future. Polls suggest the pro-independence Scottish National Party could sweep to a majority, a high bar given the proportional electoral system, and press its demands for a second referendum on splitting from the U.K.

In Northern Ireland, grievances are being nursed over its separate treatment from the British mainland in the Brexit deal struck between London and Brussels, and the province’s bitterly divided past is resurfacing as a result. More than 70 police officers were injured in a week of rioting by pro-British loyalists hurling petrol bombs. Polls suggest a remarkable shift in sentiment for a region for so long dominated by its Unionist community, with a majority now saying they want a vote on reunification with the Republic of Ireland within five years.

Even in Wales, which unlike Scotland or Northern Ireland voted with England in favor of Brexit, support for independence has risen during the coronavirus pandemic. Wales holds elections to its regional assembly on May 6 also, and there’s a chance the governing Labour Party could have to share power with the nationalist Plaid Cymru party. Plaid has pledged to hold a vote on Welsh independence within five years.

The breakup of the three-centuries-old union has been speculated over for decades, certainly long before Brexit became part of the vernacular. On their own, the developments in each of the three nations don’t necessarily spell revolutionary change, but speak to shifting cultural identities and varying degrees of political dissatisfaction with the center of power in London.

Taken together, it’s hard to ignore a growing sense that things are inexorably coming to a head, whether to diminish the union or reinforce it, and that Brexit has lent those forces greater agency.

“But for Brexit, the union would be relatively safe, but I’m not so sure now,” said Matt Qvortrup, a professor of political science at Coventry University who served as a special adviser on U.K. constitutional affairs. Change “won’t be the day after tomorrow, but give it 10 years.”

The challenge for Johnson, who was the driving force behind the successful campaign to ditch the EU in what was styled as a bid to reclaim British sovereignty, is how to cauterize the political wounds at home. His dilemma is sharpened by the fact that his Conservatives govern at Westminster, but not in Belfast, Edinburgh or Cardiff, where separate parties hold sway, reflecting the differing regional preferences of voters under a process known as devolution.

Read More: 100 Days of Brexit: Was It as Bad as ‘Project Fear’ Warned?

The most powerful of these devolved governments is in Scotland, where it runs most of the policy fields that matter in daily life, from health and education to transportation and justice. The U.K. controls areas including foreign affairs, defense and macroeconomic policy.

Johnson has thus far refused to grant the SNP-run government the legal permission it needs for another referendum to be watertight, saying the 2014 ballot was a once-in-a-generation event. Scots voted 55% to 45% to remain in the U.K. then, though at that point there was no inkling the U.K. could be about to leave the EU.

The focus now, Johnson says, should be to rebuild out of the pandemic together and that constitutional matters are an unwanted distraction. The leader of Johnson’s Conservatives in Scotland, Douglas Ross, says that “it’s recovery or referendum. We can’t do both.” He’s called on other opposition parties to team up in some election districts to stop the nationalists.

The election campaign was suspended on Friday after the death of the Queen’s husband, Prince Philip.

Another SNP landslide—the party has been in power since 2007—would escalate the standoff with London and, should Edinburgh ramp up demands, investors could take fright and the pound take a hit. There’s division within Johnson’s party over whether his government should simply continue to ignore Scotland’s calls for another shot at independence or seek to buy time and offer enough money or more powers in the hope that the issue will fade away.

The risk is that it festers instead. And the longer the dispute drags on, the greater the chance it’s resolved by demographics. Support for independence is highest among young people and the Scottish voting age is 16.

Scots in any case have never warmed to the Eton-educated Johnson, whose bumbling upper-class bearing palls beside the down-to-Earth matter-of-factness of the Scottish leader, Nicola Sturgeon.

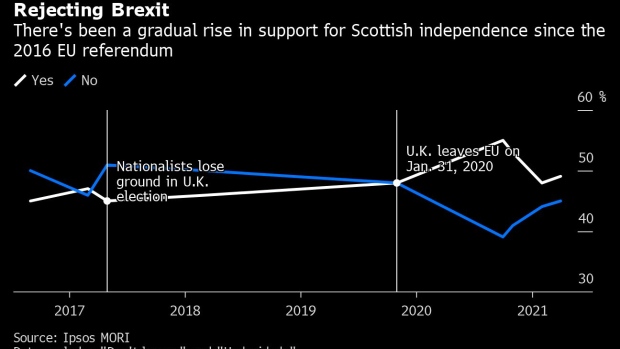

The crux of Sturgeon’s argument for another independence vote is typically direct: Brexit has changed the game. Not one district of Scotland voted to quit the EU in 2016, but it had to leave along with the rest of the U.K. anyway. The years of wrangling leading up to Brexit on Jan. 31, 2020, only hardened divisions, with the devolved administrations all claiming they were sidelined.

Some of that anti-Brexit sentiment has been converted into support for the independence cause. According to a strategy document prepared for the Conservatives and seen by Bloomberg in October, the concern is that there aren’t enough pro-Brexit voters who could counteract them.

Emily Gray, who runs pollster Ipsos MORI in Scotland, says Brexit was critical to the gradual rise in support witnessed for independence. The result is “significant doubts in Scotland about the future of the union,” she said. “Over half of Scots expect that the U.K. won’t exist in its current form in five years’ time.”

Johnson would seem to have a strong argument for the union in the shape of the U.K.’s successful vaccine rollout to date. Yet Sturgeon, not Johnson, is the face of the pandemic fight in Scotland, and the first minister says Johnson’s handling of Covid-19, recording the highest death toll in Europe, has highlighted the need for full autonomy.

The latest Ipsos MORI poll, taken between March 29 and April 4, projected the SNP would take 70 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament. With the pro-independence Greens seeing a jump in support, the momentum for a referendum looks to be growing. Some other polls have shown the SNP coming up short, but none has predicted a pro-union majority.

The situation in Northern Ireland is more complicated given its history of sectarian violence. Nationalist party Sinn Fein is stepping up its campaign for Irish reunification, saying a referendum is achievable and winnable. Polls indicate a lead for the pro-U.K. side against uniting with the south, but a slim one.

A group called Friends of Sinn Fein, once the political wing of the Irish Republican Army, placed ads in the New York Times and the Washington Post in March under the banner “A United Ireland – Let the people have their say.”

Putting such a vote in motion now would be “dynamite,” according to Bertie Ahern, the former Irish Prime Minister who played a key role in the 1998 peace agreement that largely ended decades of tit-for-tat terrorism in Northern Ireland. But that doesn’t mean it won’t happen at some point, he said in an interview last month with Bloomberg Radio. “My personal view is that it will be toward the end of the decade,” Ahern said.

That feeling of inevitability is fed by the realities of Brexit. Just along the southwest Scottish coast from where any future bridge or tunnel would be built, a new customs post is being set up to inspect goods arriving from the EU via Northern Ireland. There’s now a border in the Irish Sea.

The problem for Britain is that Scotland has become less attached to England just as Northern Ireland is gravitating more toward the republic, according to Qvortrup at Coventry University. “Socially, the U.K. is becoming less of a family,” he said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.