Mike Cagney’s Figure Technology Taps Tannenbaum as Its New CEO

Figure Technology Solutions Inc. tapped Michael Tannenbaum as its new chief executive officer, ahead of the financial-services firm’s potential initial public offering.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Figure Technology Solutions Inc. tapped Michael Tannenbaum as its new chief executive officer, ahead of the financial-services firm’s potential initial public offering.

Sales of new homes in the US bounced back broadly in March as an abundance of inventory helped drive prices lower.

Hong Kong developer Lai Sun Development Co. is considering options for a planned office tower in the City of London, including a potential sale of a stake in the project.

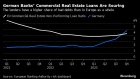

Germany’s financial regulator BaFin is taking a closer look at the real estate used by lenders to secure covered bonds known as Pfandbriefe, a €400 billion market traditionally considered among the safest in credit.

Taylor Wimpey Plc is failing to see lower mortgage rates translate into higher levels of home sales and is maintaining its forecast for fewer deals in 2024.

Dec 23, 2016

BNN Bloomberg

It was Dec. 11, 2015. Bill Morneau had been on the job for barely a month, having been appointed to the key role of finance minister by newly-elected Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in November. Morneau accepted the post, which came with a mandate to deliver on Trudeau’s campaign pledge to bolster Canada’s middle class. For many in that bracket, home ownership was becoming an increasingly out of reach aspiration. Just a week earlier, new data from the Toronto and Vancouver real estate boards underscored that reality. Home sales across the Greater Toronto Area hit a new high for the month of November, helping propel the average selling price to $632,685. Three time zones away, sales surged 40.1 per cent in Metro Vancouver, helping send the benchmark price almost 18 per cent higher to $752,500.

So, in one of his first major policy announcements since he transitioned from Bay Street executive to minister of finance, Morneau stepped in. Taking a page from the previous Conservative government’s playbook, he announced tougher down payment rules for new insured mortgages. Effective Feb. 15, 2016, the minimum payment would rise to 10 per cent for the portion of a home’s price above $500,000.

“The actions taken today prudently address emerging vulnerabilities in certain housing markets,” Morneau said that day.

But the new rule failed to rein in the country’s most scrutinized markets. Vancouver and Toronto notched record home sales in February, and it wasn’t just a stampede of buyers ahead of the new down payment rules. “Sales were up strongly from the 15th day of the month onward as well, despite the new federal mortgage lending guidelines,” said Mark McLean, then-President of the Toronto Real Estate Board, in a release on March 3.

In the months that followed, Toronto routinely broke monthly sales records while double-digit price increases continued as the norm in Vancouver, sparking concern from one of the country’s top bank executives.

“It is not sustainable and I don’t think it is healthy, there is a bit of an aberration here,” Bank of Nova Scotia CEO Brian Porter told BNN in an interview in late May. “I know OSFI [Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions] is concerned about it, the CMHC [Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation] is concerned about it, the Department of Finance is concerned about it… so I think there [are] more things the government can do."

What ensued was a year replete with warnings, bubble fears, surprise moves by various levels of government attempting to guide the market to a soft landing, and an inescapable reality that many Canadian households were stretched too thin and the economy was increasingly dependent on a sector that was raising red flags around the world.

"There is no investment as valuable -- both monetarily and emotionally -- as one's home. In 2016, the Canadian housing market went from high simmer to boiling over in almost an instant. The result was panicked buyers and sellers, sudden policy solutions and a story that dominated conversation around the dinner table, water cooler and among BNN viewers."

Even the Prime Minister acknowledged during an interview with BNN that the stakes are high for Canada’s economy.

"Rising home prices, uncertainty around being able to buy your first home or upgrade as you want to grow your family is a real drag on our economy and a real drag on Canadian’s opportunities,” Trudeau said in early June.

Housing-related activity generates about $120 billion in federal, provincial and municipal taxes, according to a report from National Bank. That covers about 17 percent of their total revenue.

With the energy sector still struggling and the Bank of Canada’s long awaited export-led recovery failing to materialize, housing has taken on a bigger role. Home construction and real estate services now contribute about 15 per cent of Canada’s total gross domestic product, and they have accounted for more than 40 per cent of Canadian economic growth over the past two years.

Politicians and housing watchdogs spent most of 2016 on the sidelines. This was despite warnings from organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development that Canada’s economy was relying too much on an “overheated” housing sector. One of the most dire warnings came from our own backyard.

“The rapid pace of price increases seen over the past year also raises the possibility that prices may be supported by self-reinforcing expectations, making them more sensitive to an adverse shock to housing demand,” the Bank of Canada cautioned in its June Financial System Review.

Politicians in Toronto and Ontario have yet take action to try and slow skyrocketing home prices. British Columbia, however, has imposed a new tax on foreign homebuyers and raised the prospect of levying a tax on homes left vacant by real estate speculators.

Morneau launched another wave of intervention in the fall, enacting stringent stress tests on new insured mortgages, closing tax loopholes used by foreign homebuyers nationwide, and launching consultations that could lead to a new risk-sharing agreement with the banks.

Home ownership is still a pipedream for most Vancouver residents, however, with home prices among the least affordable in the world. A typical detached Vancouver home is still a whopping $1.5-million. According to RBC Economics, 92 per cent of household income went toward servicing home ownership costs in that city during the third quarter – making it the least affordable market in the country, by far. Those prices, tight supply and round after round of new rules have slowed what was once a white-hot market. According to the most recent data from the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, sales in November plunged 37.2 per cent year over year.

To help residents get into the market the provincial government is now offering first-time homebuyers up to $37,500 in loans. No interest or principal payments are required in the first five years of the 25-year loans, as long as the home remains the buyer’s main residence.

Critics warn that the program will drive up prices and could increase risk for young homeowners who are already carrying crippling debt.

While homebuyers will be watching to see if Canada’s hot housing markets cool in 2017, the rest of Canada is waiting to see if the measures taken will take a toll on the overall economy.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misidentified Mark McLean as former CEO of the Toronto Real Estate Board.