Jun 27, 2022

Budget-Busting Inflation Relief Forces Asia Into Narrowing Aid

, Bloomberg News

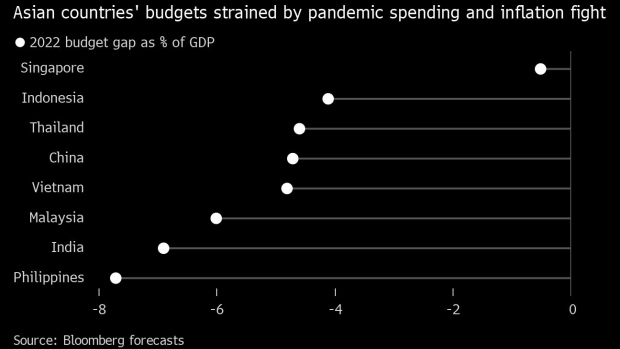

(Bloomberg) -- Asian economies that have shielded their citizens from surging energy and food prices through subsidies and other fiscal support are being forced to narrow their aim to the most-needy to ease the strain on their pandemic-battered budgets.

Indonesia and Malaysia are refocusing subsidies to ease the financial burden after two years of big spending to weather Covid-19. The Philippines’ incoming president has proposed a similar plan, while Thailand is asking its oil industry to help fund fuel subsidies, and even India is warning of the need rein in some spending. China remains an exception given muted gains in consumer prices.

Waning fiscal support couldn’t come at a worse time for the region. Inflation is yet to peak in Asia, according to economists Nomura Holdings Inc., which sees risks from global supply chain snarls and protectionism, as well as continued Covid-19 lockdowns in China and weaker harvests in India. That threatens disposable incomes and consumption, which are already under pressure from economy-cooling, inflation-fighting interest rate increases.

Authorities are “trying to address inflation pressure with a greater sense of urgency, but also being very careful with the limited fiscal resources that they have,” said Euben Paracuelles, chief Asean economist at Nomura.

Here’s a look at how governments are reorienting their policies amid shrinking fiscal room:

Indonesia

Indonesia is trying to balance between the need to extend subsidies and a commitment to bring its fiscal deficit back below the officially mandated 3% of gross domestic product by 2023. The government raised this year’s budget for energy subsidies by more than half, to 209 trillion rupiah ($14 billion), while payments to state-owned oil company PT Pertamina and state utility PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara, which help keep fuel and electricity costs steady, surged 15-fold to 294 trillion rupiah.

To avoid a blowout in the fiscal deficit, Indonesia is tapping the revenue windfall its earned from exporting in-demand commodities such as coal and palm oil. It’s also concentrating its retail and wage subsidies on low-income households, while raising prices of electricity and gasoline on typically used by higher-income consumers.

That’s expected to keep the budget deficit at 4.5% of GDP this year, a sizable jump from the 4% it initially estimated but still narrower than the 4.65% in 2021. The move has also helped cool consumer prices in Southeast Asia’s largest economy, with inflation settling at just 3.55% in May, much lower compared to its neighbors.

Malaysia

Malaysia is facing a subsidy bill for this year that’s estimated to reach a record 77.3 billion ringgit ($17.6 billion), compared with a budgeted 31 billion ringgit, a situation that may worsen as food prices rise at the fastest pace since October 2011.

A recent flip-flop over chicken prices highlights the tension between helping consumers and bolstering the budget. After earlier pledging to ditch price caps on chicken and eggs by the end of this month, which it said had caused market and supply distortions, authorities last week reversed course and pledged to keep poultry costs in check. It also held off on raising electricity and water prices.

The government, however, stuck to its plan to end subsidies on some palm oil sales from July 1, and is also considering restricting relief from elevated oil prices to lower-income groups. Currently, for every 1 ringgit of fuel subsidy, 53 sen goes to the top 20% of the population, while only 15 sen is utilized by the bottom 40% comprising low-income earners.

“The priority now is to ensure prices of essential goods are stable,” said Mohd Afzanizam Abdul Rashid, chief economist at Bank Islam Malaysia Bhd. “Removing the subsidies now would aggravate the inflationary pressure. Yes, it will cost the government, and therefore it will have to be tactful in removing the subsidies and make them more targeted instead.”

Thailand

Thailand is struggling to keep retail fuel prices in check after running up a bill of almost a $3 billion to subsidize diesel and cooking gas prices. It now expects to collect as much as 25.5 billion baht ($711 million) through a profit-sharing deal with oil refiners and gas separation plants as the nation taps new sources to fund its energy subsidy program.

Thai fuel, cooking gas and electricity tariffs are targeted at low-income groups and welfare card holders. The government said Tuesday it would only subsidize 50% of diesels price above 35 baht per liter, even if it manages to get the planned profit-sharing program going. That will ensure taxi drivers get fuel at subsidized rates and welfare-card holders get rebates on cooking gas.

“Leaning heavily on fiscal support worsens fiscal positions and still is limited in its ability to keep the lid on inflation,” Trinh Nguyen, a senior economist at Natixis SA in Hong Kong wrote in a note, while pointing that Thailand’s inflation accelerated to 7.1% in May despite subsidies while the baht weakened. “Energy remains its big Achilles’ heel,” she said.

Philippines

The Philippines has delivered a raft of subsidies to the transport and farm sectors. The initial tranches were in the form of fuel vouchers and was followed by performance-linked subsidies to public-transport drivers, based on trips made. Free rides on some rail routes were also implemented to ease consumers’ pain.

President-elect Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who takes office on June 30, has said that he prefers targeted support toward most-affected sectors instead of suspending an excise tax on oil, citing limited funds. Marcos also appointed himself as agriculture secretary to lead efforts to boost food supply, after a commodities-price surge bloated the nation’s import costs.

Singapore

The Southeast Asian business hub last week announced a S$1.5 billion ($1.1 billion) package to shield some households from surging costs of living, focused on low-income households and local businesses as inflation climbed to the highest in almost 14 years.

Even for Singapore with vast reserves and better-than-expected revenue, its support measures are “still calibrated toward helping the lower-income and vulnerable groups more,” said Brian Lee, an economist at Maybank Securities Pte. “Ultimately, it’s more efficient and bang for buck.”

India

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration last month unveiled an inflation-blunting aid package estimated to cost $26 billion, including higher subsidies as well as lower fuel taxes and import levies. That raised speculation the government would need to top-up its record borrowing plan for this year, which totals 14.31 trillion rupees ($183 billion) as revenue from other sources misses targets.

While the government has stuck to its borrowing plans so far, it indicated some belt tightening may be needed across federal agencies as it prescribed paring back non-capital expenditure.

The concern is that a further drain on the budget may cause the current account deficit-- the broadest measure of trade -- to widen, which can weigh on the rupee and make imports costlier, the government said in its monthly economic report.

“Rationalizing non-capex expenditure has thus become critical, not only for protecting growth supportive capex but also for avoiding fiscal slippages,” it said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.