May 30, 2020

Without fans or high-fives, baseball plays on in Korea

The Kia Tigers were down by two runs to the visiting Doosan Bears on a recent Sunday, when Preston Tucker came up to bat. The former Atlanta Braves outfielder was on a hot streak, batting .475 in the first two weeks of the season. He didn’t disappoint, going deep into the “Kia Home Run Zone” in right field.

Tucker hadn’t just put the Tigers on the board, he’d won an SUV, only the fourth player in the history of the Korea Baseball Organization to claim the promotional prize. Under usual circumstances, the crowd would have gone wild with cheers, songs, and choreographed dances. But the stands were empty, so Tucker rounded the bases with only his teammates to applaud him.

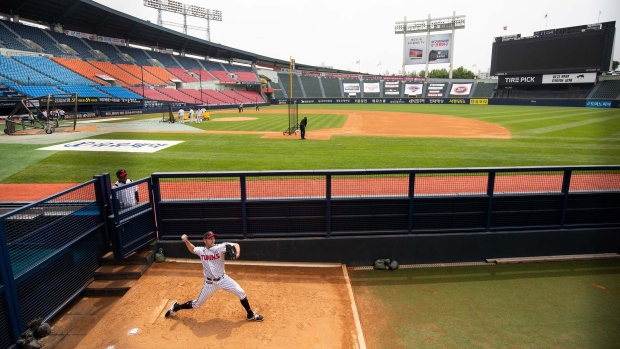

This is pandemic baseball. To comply with social distancing protocols, the KBO is playing in empty stadiums. The players don’t wear masks, but everyone else does, including the cheerleaders and the mascot. High-fives and spitting are forbidden. Canned crowd noise pumps through the speakers, and still players on the field can hear what TV commentators in the press box are saying about them.

But at least they’re playing. The world’s two bigger leagues, Major League Baseball and Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball, suspended play before their seasons began. ESPN turned to South Korea to fill the void, initially asking the foreign league to give the network its games for free. The KBO declined, and while the terms of the agreement aren’t public, the two struck a deal the day before the season began. Now sports-starved viewers in 130 countries around the world have been getting up early, or staying up late, for a baseball fix, and a glimpse into a future of fan-free contests.

Korean baseball isn’t the first sporting event to operate “behind closed doors,” as global soccer calls empty-stadium games, but it might be one of the more glaring omissions. Longtime sportswriter Heo Koo-youn describes the usual Korean game as “the world’s biggest karaoke,” a three-hour sing-off between the fans of the home team and those of the visitors, each occupying one-half of the stadium. Every player has a song, and the fans know all the words. The singing and dancing and drumming starts with the first batter and doesn’t end until the last out.

“It was actually a little distracting at first,” says the Tigers’ Tucker, who moved to Korea midseason last year. “You got to learn to hit while people are singing and cheering, just being very loud. Once you get used to it, it becomes just as normal as anything else and you start to really enjoy it.”

ESPN viewers got a glimpse of typical Korean fan behavior when Jeon Sanggyu, an LG Twins devotee, joined an LG Twins-Samsung Lions broadcast via videoconference. Sanggyu cheered, chanted, and even sang songs written for each player; his wife, also a fan, danced in the background. ESPN announcer Jon Sciambi and color commentator Eduardo Perez could only laugh, unable to interrupt the madness.

“American fans will see true passion from fans here,” says Matt Williams, a former Washington Nationals manager who’s now managing the Kia Tigers and one of four Americans on the team. Each KBO team is allowed to have three foreign players — two pitchers and a position player. “Generally in the States, folks sit there and watch the game and it only gets loud when someone hits the ball into the gap. It’s loud from the first pitch to the last.”

With the stadiums empty, the American audience hasn’t gotten the full picture, though it has seen lots of bat-flipping and plenty of home runs. The global sports drought has put Korean baseball in the spotlight. ESPN says more than 10 million people have tuned in to at least one of the Korean games it’s airing daily. Local sportscasters across the U.S. are picking up highlights for the nightly news, giving the KBO more than US$9 million worth of airtime, according to an estimate by Apex Marketing, a Michigan-based firm that tracks media exposure.

“It’s introducing the brand in local markets, places they never otherwise would be in,” says Eric Smallwood, chief executive officer of Apex. “There’s no sports, and sportscasters are still employed — they’ve got to talk about something.”

The pandemic did delay the start of Korea’s baseball season, but only by a month. South Korea has largely brought its early coronavirus outbreak under control; fewer than 270 people have died in the country of 52 million. A massive testing campaign and contact-tracing effort helped flatten the curve without requiring stay-at-home measures or bans on travel. Last month, the country became one of the first to resume international air travel to China.

The empty seats aren’t the only evidence of the global pandemic at the ballpark. Anyone entering the stadium has their temperature taken and must sign a health-declaration form, testifying that they haven’t had contact with an infected person or traveled to a country with an outbreak. Player temperatures are checked twice a day, and the league requires masks for everyone except players on the field. Reporters can’t interview players face-to-face. Players now take postgame showers at home or, if they’re on the road, at the hotel, and are urged to stay indoors after the game.

“If the situation settles, I expect we can start opening the stadiums and receive crowds, about 20 per cent to 30 per cent of the seats, from early June,” says Ryu Dae Hwan, secretary general of the KBO. “It may be hard to open 100 per cent of seats within this year.”

Meanwhile, ESPN says it plans to show KBO games through the end of the season, regardless of what happens with other U.S. sports. The broadcast is considered a marketing boon for the league and the companies that own the teams. Eight of the 10 teams are owned by South Korea’s largest conglomerates, or chaebol, including Samsung, LG, Lotte, and Kia; the other two are owned by Seoul-based online brokerage Kiwoom Securities and online game developer NCSoft. Player wages are modest compared with MLB salaries, and unlike in the U.S., there’s been no discussion about whether the athletes should bear some of the cost of lost ticket and concession revenues.

“The ESPN broadcast is a tremendous opportunity for Kia Tigers and the Kia brand,” says Hwa Won Lee, the Tigers’ president. “All in all, we believe Kia Motors will be recognized freshly in the minds of Americans, thanks to the added exposure.”

KBO baseball is often compared to the American minor leagues — Triple-A on a good day — with some Korean players hoping to play in the U.S. Chan-ho Park joined the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1994, followed by two dozen more players, including Toronto Blue Jays pitcher Hyun-jin Ryu and Arizona Diamondbacks all-star Byung-hyun Kim.

The Korean game also offers plenty of drama. Home runs are up 10 per cent this season, giving rise to unsubstantiated allegations that the KBO has “juiced” the balls. “There have been no changes at all,” says Secretary General Ryu, who attributed the improvement to new analytical tools.

The Tigers’ Tucker has slumped since winning the car, but he’s still one of the league’s top hitters, which he credits in part to the delay of opening day. “It’s been a long spring training,” he says. “You’re going to be better at the start of the season.”

Either way, more than two dozen players have started hot, batting above .300. It’s not unusual for games to feature double-digit scores and wild swings in which a team could post 10 runs in an inning.

“The idea of Korean baseball is manufacturing runs,” says the Tigers’ Williams. “Teams equip themselves with speed and guys that can handle the bat. Runners are in motion a lot. Lots of sacrifice bunting to get guys in scoring positions.”

That kind of play has been good for NC Dinos, currently at the top of the standings. Historic underdogs, the Dinos have come from behind to win six of their last 12 games. In the U.S., the Durham Bulls, the Triple-A affiliate of the Tampa Bay Rays, have adopted the Dinos, tweeting highlights and encouragement from their official account with the hashtag #WeAreNC. American fans have nicknamed the Korean team the “North Carolina Dinos,” though of course the NC is for NCSoft, the video game developer that owns the team.

The feeling is apparently mutual. Dinos fans have tweeted their appreciation, and when NC Dinos put cardboard cutouts of fans in the empty seats behind home plate, they included Durham Bulls mascot Wool E. Bull in the crowd.

—With Chris Palmeri, Kanga Kong and Jihye Le