Sep 9, 2020

California's worst wildfire season ever is about to get uglier

, Bloomberg News

California’s worst fire season on record is about to ramp up as a hot, dry autumn promises even more destruction, blackouts and evacuations.

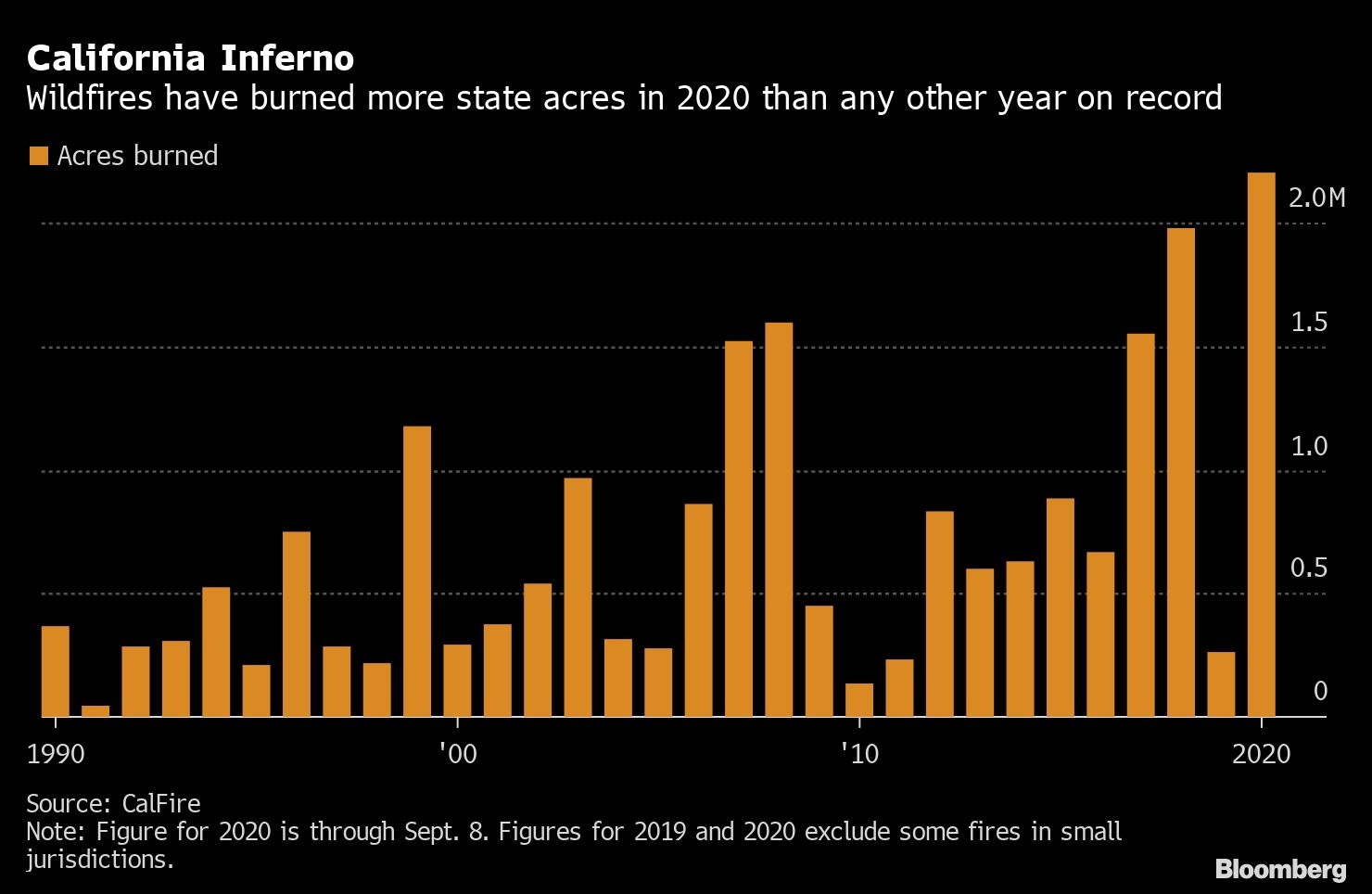

Already, 2020 has yielded three of the four largest blazes in state history, with wildfires torching an unprecedented 2.2. million acres and cutting power to hundreds of thousands of Californians. It’s going to get worse in October and November, as a conveyor belt of dry winds whip through the state, amplifying fire risk.

The danger isn’t limited to disaster-weary California. Rising temperatures and an extreme mega-drought across the U.S. West are fueling fires from Washington to Arizona. Nationwide, 40,883 blazes have consumed 4.6 million acres this year and, for the first time, preemptive blackouts by utilities to prevent fires have spread beyond California to Oregon.

“Climate change makes everything worse,” said Jacob Bendix, a professor of geography and environment at Syracuse University. Efforts to manage fire risks “will be of limited use as long as the climate is getting warmer and in many cases getting drier.”

California’s most dangerous weather tends to come in the fall, after a hot summer during which the landscape turns to tinder. This year, remnants of a tropical system brought lightning, but no rain, which helped touch off more than 700 fires, said Mike Anderson, California’s state climatologist.

Meanwhile, Death Valley reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54 Celsius), the hottest August temperature ever recorded there and the highest reading on Earth since 1931, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

“We are entering that period where our fuels are now reaching max critical dryness,” said Ashley Helmetag, a senior meteorologist at utility PG&E Corp., which late Monday began cutting power to 500,000 people in a bid to prevent new blazes from starting.

Sparking Hell

Soon, high pressure will build over Nevada and Utah, creating a system of dry winds that will whip through California’s valleys on their way to the Pacific. In the northern end of the state, those winds are called Diablo and in the south Santa Ana. If they catch a spark they can ignite hell.

Governor Gavin Newsom called this year’s fires “historic” and linked them to the changing climate in a press conference Tuesday.

“These weather conditions are challenging, and these wind conditions in particular are gonna make the next few days the most challenging perhaps we’ve had so far this year,” Newsom said.

The exact severity of 2020’s wind storms still cannot be predicted, said Anderson. But looking back at this summer’s weather can give an idea of the risks that lie ahead.

Historic Fires

Through Sept. 1, nearly 80% of California was abnormally dry and just over 54% was captured by drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The Labor Day weekend saw record heat across California. And in August, three fires ranked as the second, third and fourth largest in the state’s history, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Together, they burned 1.1 million acres.

Now, the state is blanketed in red-flag fire warnings, ahead of a cold-front that will bring dry, blaze-fanning winds. Gusts as high as 40 miles per hour could sweep the Tehachapi Mountains in Southern California and reach 45 mph in the higher elevations around San Francisco, the National Weather Service said.

The story is pretty much the same across the West, which is more than 85% dry and close to 68% in drought. The annual monsoon that brings rain and replenishment to Arizona and New Mexico was weak this year, which kept the land parched and created more incidents of dry lightning.

‘Changed World’

To reduce risk, PG&E has been clearing tree limbs away from its power lines in high-fire risk areas, installing stronger poles and covered conductors and putting in place more cameras and weather stations. Southern California Edison has taken similar precautions in anticipation of a very busy autumn. On Tuesday the utility warned it might impose its own preventative power cuts affecting 54,500 customers.

While 2020’s fires haven’t been as deadly as 2018’s -- which killed 100 people -- they have been the most extensive, burning more acreage than any other year in records going back 30 years. Still, destruction could mount with more people living on the edge of wildlands, in harm’s way.

The problem is only going to get worse, according to Bendix. When he fought wildfires in the 1980s, a 50,000-acre was considered “huge.”

“Now, look, we have fires that grow that large in a matter of hours,” Bendix said. “We live in a changed world.”

--With assistance from David R. Baker and Sam Hall.