Sep 12, 2022

Pierre Poilievre pits the 'have-nots' against the 'have-yachts'

, Bloomberg News

I would like to see politics and central banks stay apart: Strategist on Poilievre's attack on BoC

Pickup trucks pack the parking lot of the Best Western Lamplighter Inn. On an August evening in London, Ont., the hotel’s ballroom is standing room only. The Conservative Party rally is attracting rugged folks, many from outlying hamlets: farmers, health-care workers, bus drivers, pensioners, and a handful of students.

Pierre Poilievre wades into the crowd of 700, which erupts into cheers. He’s campaigning to take over Canada’s right wing and remove Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. He expresses outrage over struggling single mothers who add water to their children’s milk, 35-year-old men unable to afford rent and living in their parents’ basements, the Bank of Canada’s printing of money, taxes on fertilizer and energy, the cost of gasoline, and the mask and vaccine mandates still prevalent in Canada. He blames Trudeau for each, especially rising prices, which he labels “Justin-flation.”

Wealth is flowing, he says, “from the have-nots to the have-yachts.” Elite gatekeepers are standing in your way. “Wokeism” is destroying society. After enumerating the taxes, he lowers his voice and, with the timing of a stand-up comic, says: “I hear it got so cold in Ottawa that someone saw Trudeau with his hands in his own pockets.”

The crowd roars and then waits patiently for up to 90 minutes for a handshake, a private word, and a selfie. This year, Poilievre signed up a record-breaking 300,000 members to his party. Now the question is whether he can turn that embrace and his vow to slash spending into the ultimate political prize.

On Saturday, Poilievre (pronounced Paw-lee-EV in English and Pwa-lee-EVR in French) took a major step by winning his party’s leadership in a landslide. He sees it as the start of a populist revolution in Canadian politics, something that would’ve seemed pure fantasy just a few years ago. Rich, calm, and distinctly liberal, Canada tut-tutted the rise of Donald Trump in the US and Boris Johnson in the UK. Trudeau soared to his first victory in 2015 with talk of “sunny ways,” the idea that his nation of 38 million sets a global standard for well-planned civility, especially compared with the messy behemoth to its south.

But COVID-19, a series of modest scandals and missteps, and the inflation and insecurity punishing much of the globe are posing unprecedented challenges to Trudeau. For the first time in his seven years, more than half the country has a negative view of him. Trudeau’s troubles have prompted speculation that he won’t lead the Liberals into another election, expected in 2025, but he’s repeatedly said he intends to stay and fight.

Like the Republican and Democratic parties in the US, the Conservatives and Liberals have switched roles. The educated rich are now Liberals, while the Conservatives are increasingly the home of the working class. In Poilievre’s words, his party has gone “from suits to boots.” But, in contrast with the US, it’s pro-immigration and gay rights and doesn’t campaign on opposing abortion or making sweeping changes to firearm regulations. This is Canada, after all.

What’s noteworthy isn’t so much that the opposition is gaining at a time of general discontent. It’s that it’s doing so with a candidate so openly associated with the far right who’s drawing support from left-leaning young voters opposed to vaccine mandates. Traditionally, a Conservative in Canada must tack to the center to win and govern. Stephen Harper did just that during his decade in power starting in 2006. The last two Conservative leaders campaigned on a vow of moderation—and lost to Trudeau.

Poilievre offers no centrist message. He cozied up to the truckers’ protests against vaccine mandates last February. Some turned violent. He’s vowed to fire the governor of the Bank of Canada for stoking inflation. He labels the World Economic Forum at Davos a cabal of corporate titans and governing mandarins and says any minister of his who attends will do so on a one-way ticket. He’s also a deficit hawk in the mold of Republican Paul Ryan, former US Speaker of the House, and adamantly opposes any increase in taxes. “We will fight tooth-and-nail to stop it,” he told his party’s caucus on Monday, in a speech that drew standing ovations.

It’s all rather unfamiliar in the placid waters of Canadian politics and has led many in the liberal strongholds of Toronto and Ottawa to compare Poilievre to Trump. It’s a limited analogy at best—Poilievre is 43 and has been a fiscal wonk and parliamentarian for the past two decades, with a staid personal life. A better comparison might be with Trudeau himself. Poilievre is the age Trudeau was when he was elected. Like the prime minister, he’s a polarizing figure who preaches Canadian exceptionalism. His version stresses individual freedom, limited government, and deregulation—making Canada “the freest nation on Earth”—rather than central planning and environmental responsibility.

“If I were to start my own party from scratch, it would be the Mind-Your-Own-Business Party,” he says in an interview after his Ontario rally. “Personal agency is robbed when people can’t make their own decisions.”

Poilievre is speaking after his meet-and-greet. He’s a tactile and talented politician, a hand-holder who solicits stories of hardship that he then takes on the road. Unlike Trudeau, who has dazzle and sex appeal, Poilievre has a kind of anti-charisma charisma, the idea that he’s a plain talker from an ordinary background just like yours.

His targeted voter is someone like Adam Trojek, who was at the London event. A 37-year-old franchisee of Bimbo Bakeries, Trojek voted for Trudeau in 2015 and regrets it.

“He’s been spending money we don’t have,” Trojek says. “During COVID, he shut down too many businesses. I have a 10-month-old daughter, and she will be paying for all these policies. Poilievre keeps asking questions of the government. He talks the way I talk. He never gets the answers. But hopefully he will be the answer.”

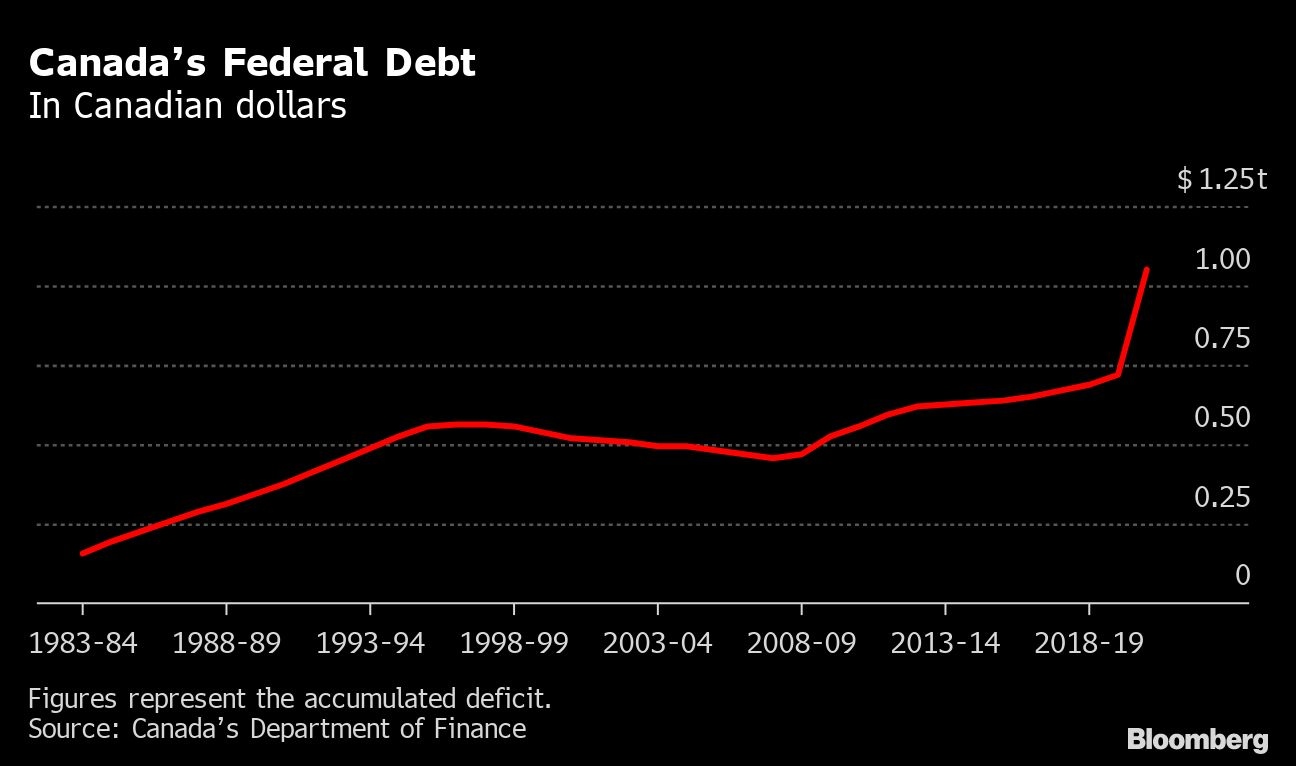

Poilievre is no political outsider. He’s been an outspoken Conservative member of Parliament his entire adult life, elected at 25 as the youngest in the chamber from a district outside Ottawa. He established himself as unrelenting at Question Period, the often raucous time set aside for lawmakers to query government ministers. He’s long made fiscal policy a central focus, going hard after big government and Liberal spending. COVID gave him powerful new credibility, as Trudeau ran up a record-smashing deficit of $328 billion (US$254 billion) in the year ended March 2021. Until then, the largest deficit in Canadian history had been $56.4 billion in 2009, during the global financial crisis.

Trudeau argued the pricey pandemic programs were necessary to keep the economy and families afloat. Poilievre predicted the spending would produce skyrocketing inflation that would hammer those holding mortgages and other debt. His prediction largely came true.

Two years ago, when he was the Conservative Party's chief finance spokesperson, the so-called shadow minister or critic, Poilievre told Bloomberg News that Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem “should not be an ATM for Trudeau’s insatiable spending appetites.” He added: “If the Bank of Canada does want to start getting more and more political, then it will be held to the same level of political accountability as other political entities.”

In a leadership debate this year, he pledged to fire Macklem if elected prime minister. His social media accounts regularly target the central bank, saying it can't be trusted to fix inflation after causing it in the first place. He called the Bank of Canada “financially illiterate.”

Slamming Macklem brings cheers at Poilievre's rallies, but it’s disturbed members of his party who fear they're sacrificing their reputation as sound economic managers. Ed Fast, who backed a rival for leadership, resigned as the party's finance critic this spring, saying he was deeply troubled. "Defending the independence of the central bank is not a Liberal talking point," Fast said in a TV interview.

Poilievre's candidacy is therefore also raising concerns about Conservative unity. The modern party is the product of a compromise in 2003, when the more establishment Progressive Conservatives merged with the prairie-based populists of the Canadian Alliance. Prior to the merger, vote-splitting on the right had resulted in three straight election victories by the Liberals; later, the Conservative Party triumphed under Harper.

Marjory LeBreton, a former Conservative senator who was deputy chief of staff to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and later served in Harper's cabinet, witnessed the painstaking negotiations that led to the merger. She says the “great accommodation” of 2003 is now “fracturing beyond repair” with Poilievre's leadership, and moderate Conservatives like her are losing their home.

“I worry that he'll transform the party into something unelectable,” LeBreton says, adding that Canadians will reject someone who only knows how to “go for the jugular.” She points to Poilievre’s support for the trucker convoy, despite its blockade of a city he represents. LeBreton, who lives in Poilievre's electoral district, says he turned his back on his own constituents.

“I’ve been a Conservative all my life,” LeBreton says. “I believe in law and order. To me, this populism just takes a sledgehammer to a cornerstone of conservatism.”

To understand Poilievre’s populism, it’s helpful to start where he did: in a lower-middle-class suburb of the western city of Calgary. The house where he grew up—Marlene, his mother, still lives there—is a split-level of gray shingle and brick with a tiny front lawn and an alley out back. On his street, at the end of the city’s light rail line, men cut their own grass. Pierre was a paperboy for the Calgary Sun and a high school wrestler. He was born to an unwed mother who at 16 gave him up for adoption to the Poilievres, teachers from the neighboring province of Saskatchewan. His father came from French-speaking stock; his mother, English. His younger brother, also adopted by the Poilievres from the same biological mother, works for a Calgary councilman.

It would be hard to imagine a clearer contrast with the background of Canada’s current leader. Trudeau’s father, Pierre, was a larger-than-life prime minister, his mother, Margaret, a 1970s symbol of glitz and glamour. Trudeau came of age in sophisticated Montreal with a Kennedy-esque pedigree amid lavish comfort. Poilievre not only comes from the humblest of stock but also from the western province of Alberta, which has long resented the eastern establishments.

“Out here on the prairies, we get it,” says Rick Bell, a columnist for the Calgary Sun, the paper Poilievre once threw onto doorsteps. Sitting in a diner booth where he interviewed Poilievre several months ago, he continues to explain how most there see things: “We’re outsiders. Things need fixing, and they are the very things that were produced by ‘sunny ways.’ Pierre brings that outsider-ness and is taking on the establishment. For Canada, this is very bold.”

Calgary, gateway to the Canadian Rockies, may consider itself marginalized, but it’s hardly poor. It owes its substantial wealth to oil, gas, and cattle, industries with long traditions of opposing government regulation. There’s been a Western US influence from homesteaders, oil workers, and Mormons who moved north. Like Houston or Denver, Calgary holds dearly to its Old West ways, labeling its highways “trails” and its fairgrounds “the Calgary Stampede.”

Its university has famously produced a set of ideas known as the Calgary School, an echo of the free-market Chicago School. Ex-Prime Minister Harper emerged from that incubator, as did Poilievre. Young Pierre was active in the university’s conservative club and in 1999 was a finalist in an essay contest on what he would do if elected prime minister. He’d leave Canadians “to cultivate their own personal prosperity and to govern their own affairs as directly as possible,” he wrote in an early version of his current ideology. He began a political communications company after graduation and was then hired by Stockwell Day, a Conservative politician who took him to Ottawa.

Day became foreign affairs shadow minister and Poilievre his policy aide. As Day recalls, “One cold winter night, he came into my office and said, ‘I am thinking of running for a local constituency here in Ontario.’ I said, ‘Calgary would make more sense. Here nobody knows you, you have a French name, and you’ll be seen as a young punk outsider.’ He didn’t listen and door-knocked his way to victory.”

Poilievre has many qualities that are rare for his party and broaden his appeal. He comes from the West but represents the East. He has a French name and speaks excellent French. He’s married to a Venezuelan immigrant to Quebec with whom he has two small children, yet he’s seen as having an Anglophone’s outlook. Unlike American politicians on the hard right, he’s pro-immigrant and doesn’t want to touch abortion rights. On gay rights, he says, “It should be freedom for everybody, including gays and lesbians, to live their own lives in happiness and without interference from the state.” His focus on pocketbook issues is relentless. “When you inflate asset prices, what you do is you shut the lower-income working classes out of property ownership while inflating the wealth of those who have,” he says.

Poilievre wants to loosen Canada’s green regulations. He doesn’t deny climate change but favors stepping up oil production and pipeline construction. He argues that Canadian environmental standards are superior to those in the Middle East and Asia, and the production fosters employment at home. “Canada accounts for about 2 per cent of global emissions, so what it does really makes little difference,” argues Ted Morton, a retired political scientist who was central to the Calgary School in the 1980s and ’90s. “It’s wrongheaded for Canada to sacrifice oil and gas for climate change, and that’s what Trudeau is doing.”To some political observers, Canada today feels like 1979 during the rise of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK. There’s runaway inflation, an energy crisis, and a Russian threat. Impatience with government missteps and COVID mandates is palpable; Air Canada flights require masking, and pilots all but apologize for it during their takeoff announcements.

Poilievre’s campaign videos feature him talking about issues such as a gummed-up bureaucracy, high taxes, and the loss of tradition. They’ve gone viral. He terrifies many who consider him a demagogue for his embrace of anti-vaxxers and attacks on Davos and the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. as woke gatekeepers.

Three years, the time before a general election is due, is an awfully long time in politics. But no one counts Poilievre out. Because of Canada’s multiparty politics, he needs only to add a small percentage of non-Conservative voters to triumph in an election. “He’s building on a politics of grievance and is really good at coming up with slogans,” says Lori Williams, a political scientist at Calgary’s Mount Royal University. “We have seen conservative populist leaders win all over the world. Why would Canada be different?”