Apr 20, 2021

CN rekindles century-old rail rivalry with Kansas City Southern bid

, Bloomberg News

CP Rail says CN Rail's offer for Kansas City Southern 'illusory and inferior'

Canadian National Railway Co.’s bid to wrest Kansas City Southern away from Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. is rekindling a century-old rivalry and pitting former colleagues against each other.

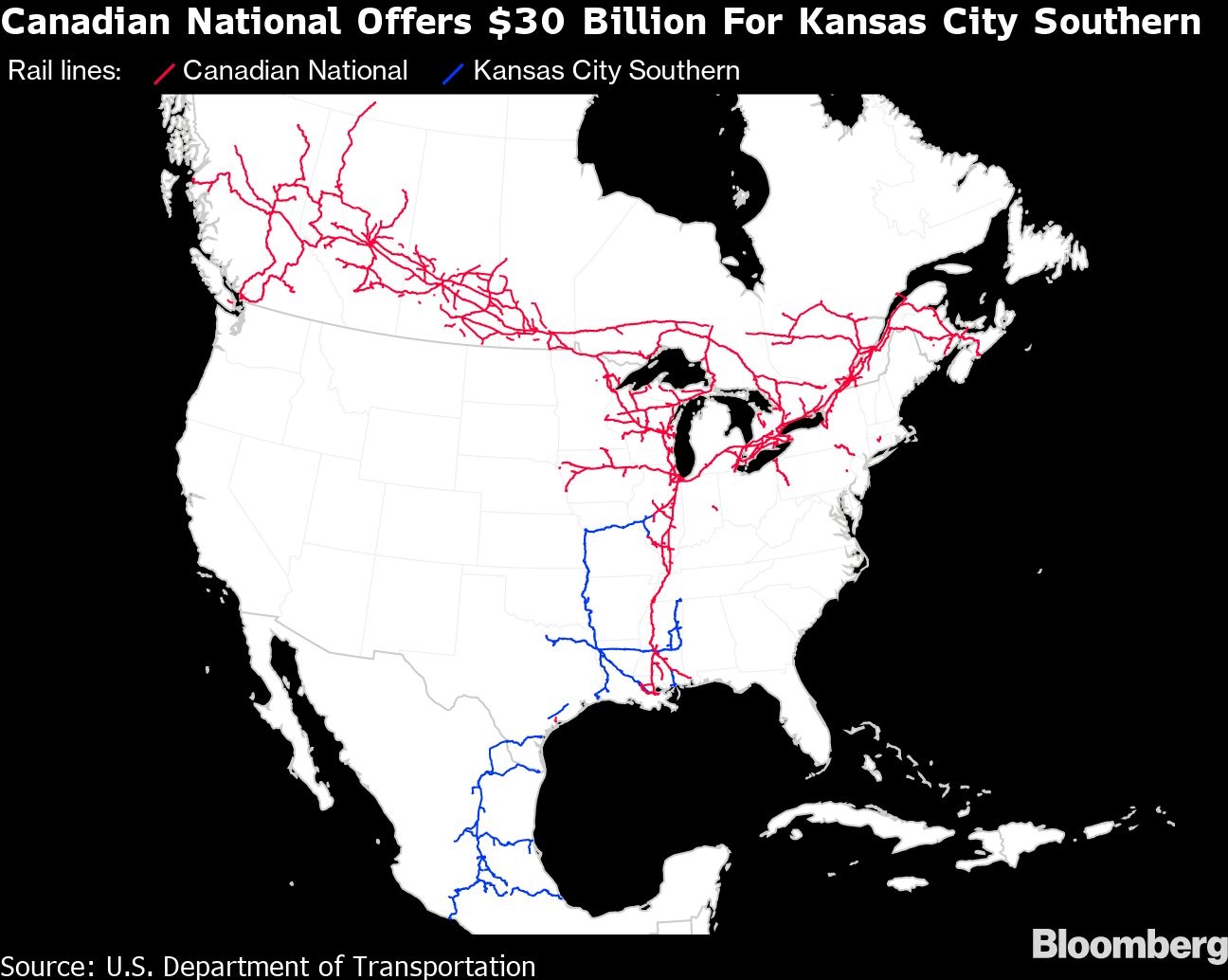

The US$30 billion takeover fight sees Canadian National Chief Executive Officer Jean-Jacques Ruest attempting to grab a prize long sought by Canadian Pacific CEO Keith Creel, who once served alongside him as Canadian National’s chief operating officer. It’s one of the biggest railway deals of the past two decades, with the winner gaining control of a sprawling network that crosses the three countries in North America’s trade alliance.

The two sides took shots at each other after Canadian National unveiled an unsolicited bid that’s nearly 20 per cent higher than Canadian Pacific’s offer.

Canadian National is “the better bid, the better partner, the better railway,” Ruest said on a conference call with analysts. “The result will be a safer, faster, cleaner and stronger railway than any other proposed combination for KCS.”

Canadian Pacific said its larger rival’s offer is “illusory and inferior” because it creates major antitrust concerns. “The Canadian National management team has significantly underperformed over a decade and has a track record of underdelivering against its own projections,” Canadian Pacific said in a statement that also attacked CN’s safety record.

The rivalry between Canada’s two dominant railways has been hot ever since Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management LP won a proxy fight in 2012 for control of Canadian Pacific’s board.

Ackman installed Hunter Harrison, who had gained acclaim for turning around Canadian National while he led the company from 2003 to 2009, as CEO. Harrison then poached Creel.

The companies have fought publicly and sued each other; Canadian Pacific even paid $25 million to settle a claim that accused it of using former Canadian National employees and client lists to take CN’s customers. But this time, the stakes are much higher.

“It’s a real escalation of this century-old corporate rivalry,” Dimitry Anastakis, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, said in an interview. “It really does change the dynamic for both companies whether they get it or not, and it can be a game-changer.”

The balance of the Canadian rail system is also at stake. Canadian Pacific is trying to match its larger rival’s reach into the U.S. and even go one up by tapping into Mexico. If Canadian National wins the bidding, it would isolate Canadian Pacific to mostly its home country, while swelling its U.S. business and extending its reach to one of the largest ports in southern Mexico.

‘Betraying’ CN

Canadian Pacific’s hiring of Harrison sparked a legal battle over $40 million in retirement benefits he was owed by Canadian National. It was settled when Harrison agreed not to hire about 60 of Canadian National’s top executives for more than three years.

That deal cleared the way for Canadian Pacific’s hiring of Creel in 2013. It ultimately opened a path to the top for Ruest, who became interim CEO in March 2018 and took the job on a permanent basis four months later.

But the bad blood continued to simmer under Harrison’s reign at Canadian Pacific, and in 2016 it paid to settle the suit over customer-poaching.

“It was seen within as CN that Hunter was betraying CN,” Karl Moore, a management professor at McGill University in Montreal, said in an interview. “We don’t do this in Canada.”

Ackman sold his Canadian Pacific stake in 2016 and left the board. Harrison departed soon after and took over as CEO of CSX Corp., but died in December 2017 at age 73.

While the Ackman-Harrison episode marked the most pitched battle between the companies in recent memory, the two enterprises have been competing for more than a century.

Canadian Pacific, incorporated in 1881, played a key role in the nation’s formation as its transcontinental line was pivotal in convincing British Columbia to join the newly-independent country. Canadian National was created in 1919 out of a collection of government-owned railways.

The very formation of Canadian National made Canadian Pacific “apoplectic” that it now had to compete with a government corporation, and Canadian National’s public backing was a sore spot for decades, Anastakis said. Even when Canadian National was privatized in 1995, it was initially run by Paul Tellier, a former high-ranking government official.

The two firms also reflect regional and political tensions in Canada, with Calgary-based Canadian Pacific representing the western, conservative part of the country, and Montreal-based Canadian National embodying the more liberal, elite character of the east, Moore said -- as well as the bilingual nature of Quebec.

Despite the resurgence in their rivalry, the fact that at least one Canadian railroad may be positioned for a transformative acquisition is a positive for the country, which has often seen its own major enterprises bought out by international rivals, Anastakis said.

“You’ve got two gigantic Canadian rivals duking it out for an important American railway,” Anastakis said. “That’s a nice role reversal from a lot of Canadian business history.”