Jul 3, 2019

Charter Schools Are Victims of Their Own Success

, Bloomberg News

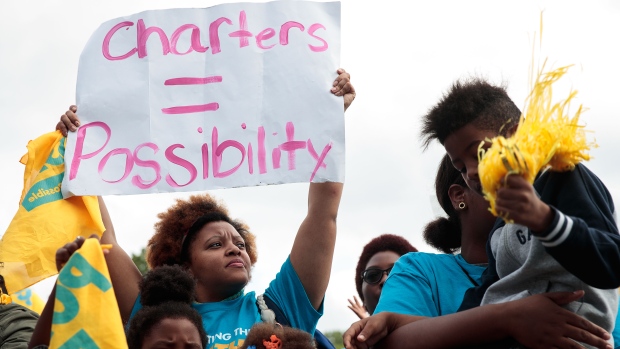

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Advocates like to say that charter schools punch above their weight: Compared with better-funded, established public schools, high-performing charters produce students who learn more, do better on standardized tests, and are more likely to graduate from college. Charter schools are also disproportionately polarizing. Despite accounting for just 7% of America’s public schools, they have become the system’s biggest source of conflict.

The head of the largest teachers’ union says that the charter-school industry “want[s] to create horrible public schools.” The NAACP has called for a “moratorium” on new charters. Legislators in California, which has the country’s largest number of charter schools, are considering bills to curtail their growth. According to a survey by the journal Education Next, only 44% of the public supports the formation of charter schools, down 10 points in the last five years.

What’s most surprising is the group most responsible for that drop: Democrats. Just 36% of Democrats back charter-school expansion; among white party members, barely one in four express support. In contrast to the administrations of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, who promoted charters as a way to spur reform of the public-school system, the leading candidates competing for the 2020 presidential nomination generally aren’t endorsing them. Bernie Sanders wants to suspend all federal funding for charters and create a commission to study their impact on traditional public schools. Other contenders, including Joe Biden and Elizabeth Warren, call for an end to federal funding for charters run by for-profit companies.

Why the backlash? Longstanding opposition to charters from teachers’ unions, who wield strong influence over the Democratic nomination process, is undoubtedly a factor. So is the fact that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, among the least popular members of Donald Trump’s cabinet, poured millions of philanthropic dollars into the charter movement. But the main causes for the growing political unease with charters are the schools themselves: They are victims of their own success.

First established in the early 1990s as laboratories for innovation, charter schools now educate more than 3 million students, a sixfold increase since 2000. That growth has come with costs. High-quality charter operators have notched impressive gains, yet the industry remains plagued by cases of weak oversight, profiteering and poor management — notably, in DeVos’s home state of Michigan. Charter schools have played a critical role in improving outcomes and expanding choice for minorities and low-income families. But at a time when funding for public education remains flat and many school districts are struggling to do more with less, even success can start to look like a threat.

In much of the country, charter schools operate in a regulatory gray zone. While they receive public funds and require authorization by a state-recognized body, they are privately managed. They are generally permitted to design their own classroom curricula, hire non-union teachers, and draw students from outside their immediate neighborhoods.

Charter opponents say these arrangements undermine the mission of existing public schools, siphoning away students and the dollars that follow them. In fact, the opposite is true. In 14 urban areas with high charter concentration, charter schools receive 27% less than traditional schools in per-pupil funding from local, state and federal sources. Charters also enroll a higher percentage of poor and minority students.

Considering their limited resources, charter schools have delivered meaningful results for their students — though some groups benefit more than others. A 27-state analysis by researchers at Stanford University found that students at charter schools gained the equivalent of eight days each year in reading over their peers at traditional schools, but saw no differences in math learning.

The biggest jumps were made by low-income African-Americans and Hispanics learning English as a second language. Those groups gain more than an additional month’s learning each year in both math and reading if they attend charter schools. A recent study by the Fordham Institute points to one possible explanation: Black students at charters are about 50% more likely to have a black teacher than they would if they attended a district school — a “race match” effect that has been shown to decrease dropout rates.

Even so, the quality of the charter-school sector is highly uneven. Schools that belong to established nonprofit charter management organizations (CMOs), which account for one-fifth of all charters, have raised test scores and set up their students for long-term success. KIPP, a network that operates more than 200 charters enrolling 96,000 students nationwide, has seen 36% of its alumni complete college — three times higher than the national average for low-income students. But online charter schools — which represent a small segment of the charter sector and are largely run for profit — have shown disappointing student growth relative to mainstream public schools.

Proponents of charters say there’s a simple solution for underperforming schools: Shut them down. Yet policy makers have struggled to settle on a formula for determining when schools should lose their charters, and who should decide. Around 5.2% of low-performing charter schools close each year, compared to 3.4% of district schools.

More of them probably deserve to go. Of the 44 states plus the District of Columbia that have laws governing charter schools, fewer than half set minimum benchmarks for automatically closing bad schools. Even in states that do, the thresholds for triggering closure are too low, or enforcement is too weak. In Michigan, where 80% of charters are operated by for-profit entities, schools can be forced to close if they score in the fifth percentile or lower for at least four years. That may have reduced the numbers of truly abysmal schools, but plenty of underachieving charters remain: A 2016 study found more than seven in 10 performing below the median, in a state where test-score gains are among the lowest in the country.

That low-performing charters stay open has undermined one of the movement’s most potent political arguments: Good charters not only provide an alternative to traditional public schools but actually help to improve them. Studies of the impact of charters in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Massachusetts found a “spillover” effect, with test scores rising in district schools located near high-performing charter schools.

In New York, the introduction of charter schools spurred investment in district schools, with instructional spending rising by 8.9% for schools that share facilities with charters. Similar progress is evident in Washington, D.C., where nearly half of all public-school students attend charters. At both charters and traditional schools, per-pupil spending is well above the national average — and by some measures, tests scores for all students have risen faster than in any other urban district in the country.

Ultimately, much of the war over charters comes down to money. Opening up the public education system to competition from privately operated charters is politically sustainable only if existing schools — and their teachers — believe they’re not being shortchanged. With nearly half the states spending less on education than before the crash, that’s a hard argument for charter advocates to win. For unionized teachers coping with dwindling school budgets and stagnant pay, charters present an all-too-convenient scapegoat.

Coordinated federal and state policies that promote expansion of proven charter models, while insisting on tougher standards for low-performing and for-profit charters, would go some way toward burnishing the sector’s reputation. Without greater political commitment to raising the standards of all public schools, however, the promise of charters will remain unfulfilled. Contrary to prevailing Democratic thinking, charter schools are enhancing, not undermining, America’s public-school system. But they’re not enough to save it.

To contact the author of this story: Romesh Ratnesar at rratnesar@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Clive Crook at ccrook5@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Romesh Ratnesar writes editorials on education, economic opportunity and work for Bloomberg Opinion. He was deputy editor of Bloomberg Businessweek and an editor and foreign correspondent for Time. He has served in the State Department, and is author of “Tear Down This Wall.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.