Jun 26, 2020

Charting the Global Economy: That’s Not a V-Shaped Recovery

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- It’s tempting to take the recent rebound in business confidence and activity measures as a sign that the global economy is well on track to make up for its coronavirus-induced losses -- except it’s misleading evidence.

Here are some of the charts that appeared on Bloomberg this week, offering insight into the real state of the global economy:

Purchasing managers’ indexes from Asia, Europe and the U.S. are among indicators that have recorded impressive gains that look just like the V-shaped recovery many once spoke about. But that short-term rebound doesn’t say much about the more important medium-term outlook. On top of that, measures of demand, employment and prices in the PMI offer reason for caution.

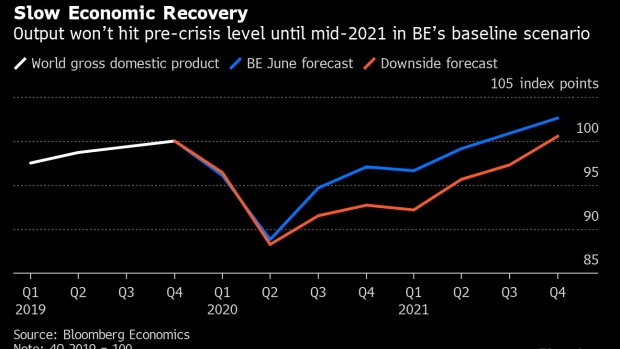

According to calculations by Bloomberg Economics, it may take the global economy until the end of next year to fully recover from the pandemic. Its baseline scenario sees output shrinking 4.7% in 2020. In a more pessimistic view -- assuming the pandemic runs longer, recession scars slow the recovery, and the ceiling on activity from residual social distancing is lower -- global GDP contracts 6.7%.

Even though many economies have already passed the trough, uncertainty about new waves of infection is keeping a lid on spending and investment. That means many parts of the world will see worse contractions this year than during the financial crisis. The International Monetary Fund has downgraded its outlook again and now foresees a drop in GDP of 4.9%.

Emergency spending by governments is set to push the global debt ratio above 100% for the first time. The IMF forecasts the burden this year alone will jump by close to 19 percentage points, dwarfing the increase after the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

U.S. consumer spending surged by a record in May but the annualized rate of household outlays remains well below pre-pandemic levels, indicating a long road to recovery from a deep recession.

The misery spreading through the U.S. economy as a result of the pandemic may well have political consequences. An index combining unemployment and consumer prices has spiked to an extent that historically would suggest a loss for the incumbent party in the White House.

In China, where the coronavirus first broke out, the economy continued its slow recovery in June, with a better performance in the services sector and among smaller companies tempered by the still-grim global outlook.

Central banks have been key to rekindling growth momentum. Demand for Bank of Japan loans aimed at helping struggling companies have jumped fivefold to 8.3 trillion yen after the introduction of a second loan program.

It’s the same story around the world, as seen in the Bank of England’s balance sheet. Governor Andrew Bailey broached the topic this week, arguing in a piece for Bloomberg Opinion that balance-sheet reduction might come before interest-rate increases by the bank.

In Germany, another V was on display, this time capturing hopes among businesses that the billions of euros of support from central banks and governments will spearhead an economic recovery in the latter part of this year.

In South Africa, support measures will blow out the government’s budget deficit to 15.7% of GDP, the most in at least three decades. The country intends borrowing $7 billion from international financial institutions including the IMF. It’s already secured a $1 billion loan from the New Development Bank.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.