May 3, 2021

Chasing red-hot profit growth is a recipe for stock-market pain

, Bloomberg News

Bears think tech earnings aren't sustainable but fundamentals are strong: Wedbush Securities' Ives

It came as a shock on Wall Street the last few days, how much better the world’s biggest companies were doing than anyone thought. Also unexpected was what the market made of those results. Despite big earnings beats, the share-price performance of the vaunted Faang cohort has been mediocre.

Then again, maybe that shouldn’t be surprising. Thirteen months into the COVID-19 recovery rally, Wall Street researchers have become focused on the question of when in the cycle it pays for investors to wean themselves off companies showing the highest growth rates. An academic study says that paying for companies where a lot of profit optimism is priced in has been one of the worst strategies for the last four decades.

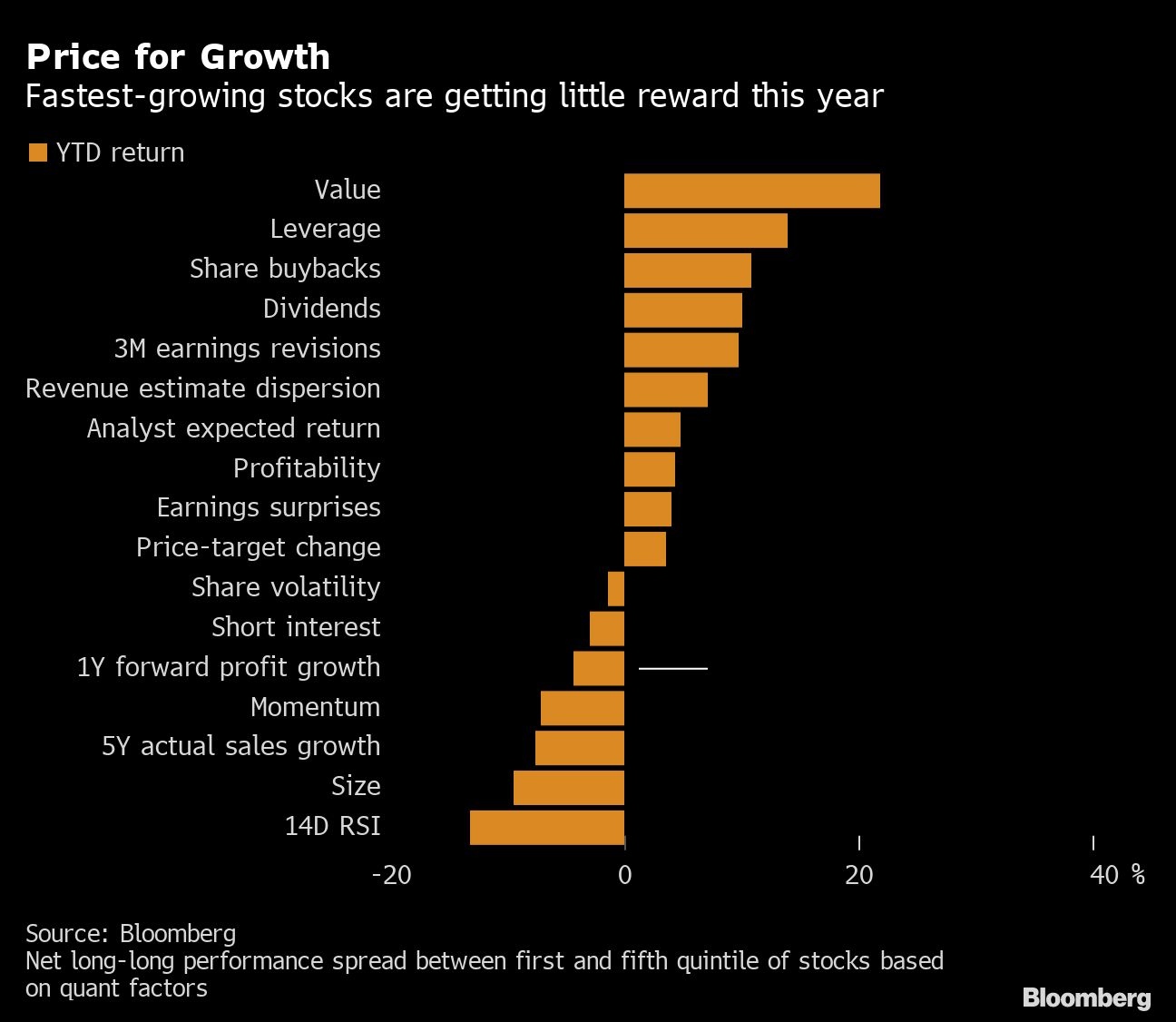

With corporate income quickly vaulting back to pre-pandemic levels amid the best expansion in a decade, the fastest growers are getting no respect. A long-short strategy based on forecast income growth for Russell 3000 stocks -- buy the top quintile against the lowest -- has lost more than 4 per cent this year, trailing all but four of the 17 quantitative styles tracked by Bloomberg.

Call it the peril of high expectations, a condition that is getting increasingly relevant today as analysts keep ratcheting up estimates. For now, the higher bars are proving no hurdle for companies to clear, though negative reactions to earnings from stocks like Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc. and Tesla Inc. suggest a ceiling may be in after the market’s US$25 trillion rally.

“If the blowout results can’t really move things higher, what can and what will?” asked Carter Worth, head of technical analysis at Cornerstone Macro LLC. “What possibly could be said or revealed, in the coming two to five months, that tops what has just been revealed? What advances the market from here?”

To be sure, in a year when all sell signals have been nothing but a sure way to lose money, finding fault with the current robust expansion is like looking a gift horse in the mouth. Almost 90 per cent of S&P 500 companies that reported have beaten analysts’ profit estimates, the strongest showing since Bloomberg began tracking the data in 1993.

Based on reported results and analyst estimates for companies that have yet to announce results, profits in the first quarter probably surged 46 per cent from a year ago, the fastest since 2010, data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence show.

But if history is any guide, placing too much faith in perceived high-growth can be a dangerous game. In a recent update to their paper entitled “Diagnostic Expectations and Stock Returns,” researchers including Pedro Bordalo of the University of Oxford, Nicola Gennaioli of Italy’s Bocconi University and Rafael La Porta of Brown University found that between 1981 and 2015, stocks with the most-optimistic long-term profit growth forecasts trailed those with the most-pessimistic forecasts by 12 percentage points a year.

Such is the burden for companies whose shares embed extremely high expectations, a dream that they’d one day dominate their industries the way Google did in the online search business. Needless to say, it’s a dream very few firms are able to achieve.

“Over the past 35 years, betting against extreme analyst optimism has been on average a good idea,” the researchers wrote. “Intuitively, fast earnings growth predicts future Googles but not as many as analysts believe.”

While the study focused on individual companies, the concept appears to apply to the entire market these days, as policy support and vaccines fuel hopes for a roaring economy. So much optimism is priced into stocks from the return-to-normal activity that it leaves the market vulnerable to hiccups such as supply chain disruptions, according to Morgan Stanley strategists led by Mike Wilson.

“Dreaming of a reopening is easier than actually doing it,” Wilson wrote in a note. “We see growing cost issues, in the near term, that aren’t priced. There is also a question of how much pent-up demand really exists.”

After being blindsided by the pandemic and staying too conservative about corporate America’s earnings power, analysts are now busy upgrading their forecasts at one of the fastest clips in years. But there is a risk hidden in the slope of the earnings trajectory.

Ned Davis Research grouped S&P 500 earnings growth since 1927 into five brackets and found that unless it’s really bad -- down 25 per cent or more from a year ago -- income growth tends to have an inverse relationship with market returns. When the rate of expansion topped 20 per cent, as is the case now, the S&P 500 rose at an annualized 2.4 per cent, or one quarter of its average returns of all periods.

The seemingly odd behavior, according to Ned Davis, founder of his name-sake firm, has to do with the market’s inclination to always look ahead. And once the good news on profits is priced in, it doesn’t leave much room for stocks to keep going.

One example of that is the market’s performance surrounding President Donald Trump’s tax cuts. The S&P 500 rallied roughly 20 per cent in 2017 in anticipation of the boost to earnings when the policy took effect the following year. Then 2018 came, earnings were boosted, and the market fell.

Of course, with the pandemic driving monetary policy and the economy into uncharted territory, nothing in the past may be applicable now. Still, with the S&P 500 trading at 22 times forecast earnings, hovering near the highest multiple since the dot-com era, a moment of reckoning may be approaching.

“The risk in chasing here and now is that you are paying a premium multiple for earnings strength that the market has already been anticipating for several months,” said Michael O’Rourke, chief market strategist at JonesTrading. “We can have great earnings growth and earnings beats and still have the market remain flat or even sell off.”